MotoGP first ventured overseas for the finale of the 1961 season, when a handful of hardy Continental Circus players parked their rusty little vans (and caravans, if they were lucky) and boarded a plane to Buenos Aires, Argentina, via New York.

Only six riders started the premier 500 GP at the Autodromo Juan y Oscar Galvez — built to celebrate the country’s Formula 1 car legend Juan Manuel Fangio — and most of them were locals.

Frank Perris was one of the few Europeans on the grid. The Brit raced for the win, until his Norton’s gear lever fell off, so he rode the rest of the race in third gear. He still finished on the podium, albeit ten laps behind local winner Jorge Kissling.

The real interest was in the 125cc race, because this was the only championship still up for grabs. Honda sent a small armada of its RC RC144 125 twins to Buenos Aires to help its Aussie rider Tom Phillis beat East German MZ rival Ernst Degner to the title.

Degner had led the championship on his factory MZ but had just defected from his communist masters, so he borrowed a British-made EMC (basically a copy of the MZ) for the title decider.

Degner (second right) lost his 1961 world title chance when his bike failed to turn up for MotoGP’s first-ever flyaway race, in Argentina

Woollet

Degner was convinced that East Germany’s murderous Stasi secret police were after him. And with good reason, because the Stasi had a habit of killing defectors, pour encourager les autres. So he bought a handgun in downtown Buenos Aires.

Degner’s championship hopes evaporated when the EMC didn’t turn up. He believed the Stasi had made contact with old Nazis hunkering down in Argentina to make sure the bike got no further than New York.

MotoGP’s next flyaway was Daytona, for the first United States GP of 1964. Skint Brit privateer Alan Shepherd was convinced he would have a chance of winning the 250cc GP if MZ loaned him one of its missile-fast tandem twins.

The local Yamaha importer had bribed customs staff and hidden Kawasaki’s freight

However, the Americans wouldn’t grant a visa to genius MZ engineer Walter Kaaden (this was the height of the Cold War) so Shepherd drove his little van the 900 miles to the East German border, where Kaaden wheeled an MZ 250 through the Iron Curtain and Shepherd set off for Daytona alone.

The MZ was super-fast, at least it was when Kaaden was around to solve the conundrum of jetting, ignition, squish bands and so on. But he wasn’t, so the bike was a slug. Shepherd was so desperate he telephoned Kaaden before final practice. The call cost £1 per minute (£20 today), money Shepherd didn’t have.

Kaaden quickly gave Shepherd the jet sizes, ignition settings and squish measurements required for the conditions and the Cumbrian won the race, lapping everyone else.

In the late 1970s MotoGP returned to South America, for the Venezuelan Grand Prix. The 1978 event was significant, because it marked Kawasaki’s first full-factory attack on the world championships, with its brand new KR250 and KR350 tandem twins (another design stolen from Kaaden).

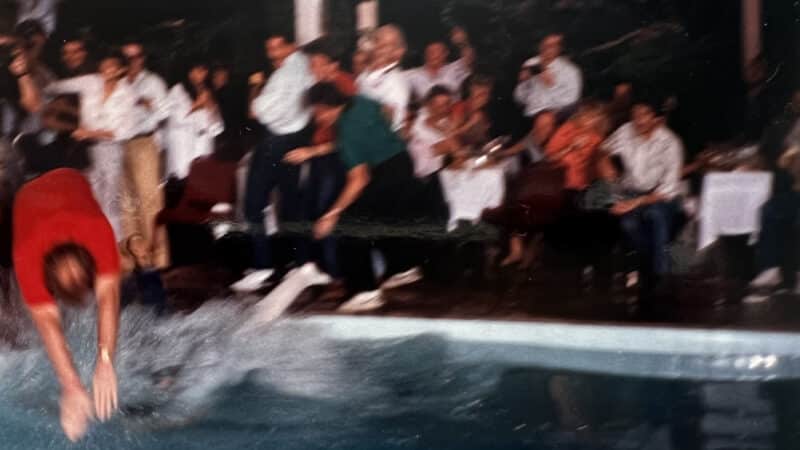

The parties were bigger than the racing at the Brazilian GP in Goiania. Judges on the beauty contest panel include Randy Mamola and Wayne Gardner

Oxley

However, when Kawasaki mechanics arrived at customs to collect their bikes they weren’t there. The team’s local fixer soon found out what was afoot. The local Yamaha importer had bribed customs staff and hidden Kawasaki’s freight in a dark, dusty warehouse in the outskirts of Caracas, so that young local Yamaha star, Carlos Lavado, could win the 250cc and 350cc GPs.

More guns. The KRs were only released after the fixer had driven into the warehouse car park, firing warning shots in the air.