“Kawasaki said they wanted to train me, so I had a month in the drawing office, a month in the workshop and a month on the dyno. I was very lucky, it was a fantastic opportunity.

“There was me and a guy from America. On the first day they said there’s 40 wheels and there’s 40 tyres, so put those 40 tyres on those 40 wheels and when you’ve done that, sweep the workshop floor. The American said, I’m not here to do that kind of stuff, so he was put on a plane home and I stayed.

“I enjoyed it. It gave me a strong grounding of understanding the Japanese, which stood me in very good stead. Then there was another big surprise: oh, by the way we’ve also built a 350, which they hadn’t even told us about. Kawasaki hit the ground running with these bikes in 1978. They’d done a complete redesign and got on top of the twin firing order.”

“The new chassis was designed by Kinuo ‘Cowboy’ Hiramatsu, who also designed the 250/350 frame and was later headhunted by HRC. They called him Cowboy because he used to walk around in a pair of way-too-big racing boots that someone had given him.

“Kawasaki got there by perseverance and by Japanese attention to detail. The Japanese will take an idea and develop it to death, where perhaps others run out of money or ideas.”

He said to Fukui, ‘are you stupid? Did you pay attention at school? Because you don’t know what you’re talking about!’

In 1980 the factory took the next step and built a 500, the square-four KR500 that was either a doubled-up KR250 or a Suzuki RG500 rip-off, depending on which way you looked at it.

Ballington rode the 250 and 500 in 1980, and would’ve completed a 250 hat-trick if he hadn’t fallen dangerously ill with a gangrenous perforated gut, the result of an earlier injury.

“Kork was one of the first professionals. He kept himself fit and he was super smooth, which made him untouchable on road circuits like Imatra and the old Brno and Spa. Kork thought a lot about how to go quicker, focusing on being faster through the bits that weren’t so dangerous.”

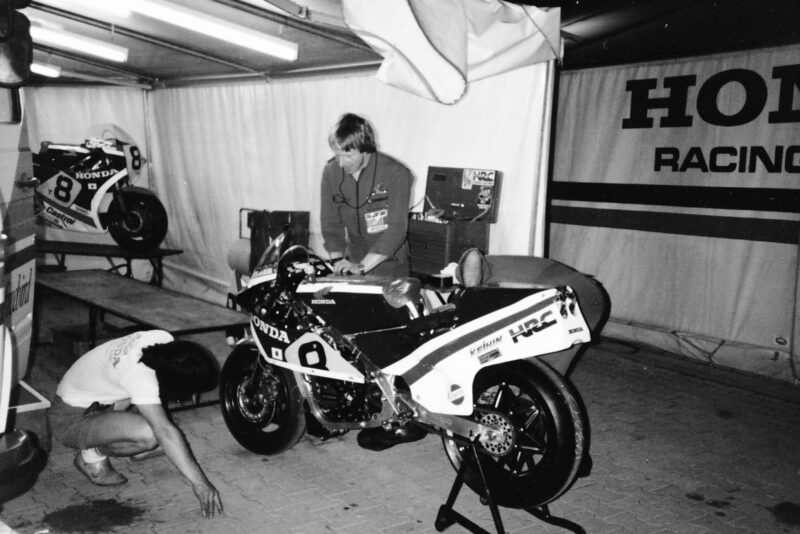

After his move to HRC Shenton works on Takazumi Katayama’s NS500 triple

Shenton archive

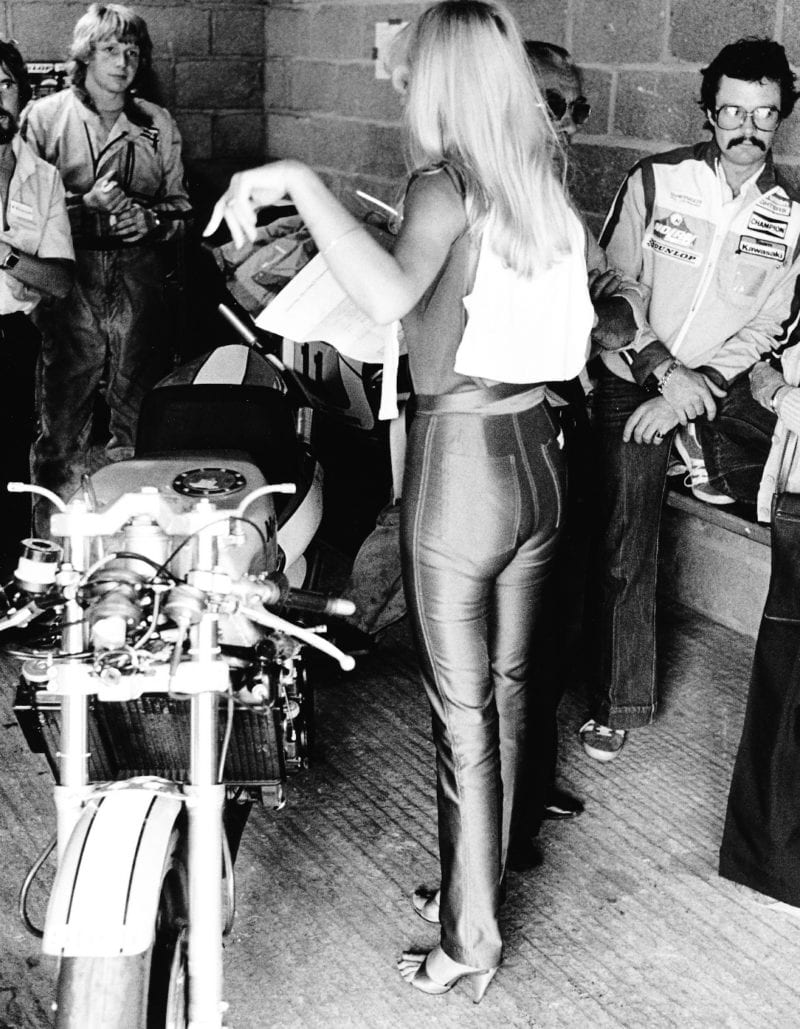

If the racing was dangerous, the Sunday nights were also quite scary.

“I remember being in a rentacar with Dozy and a few other guys from Kenny Roberts’ team. It was Sunday night in Misano and Kenny jumped out of a first-floor restaurant window onto the roof of our car, collapsing the roof down on top of us. Then he insisted we drive through the town with him sitting there.”

The KR500 promised much but never quite delivered. Hiramatsu tried to push things forward with a monocoque frame.

“The 500 was way overweight and probably way too stiff, which we didn’t realise at the time; though we did have an inkling about stiffness – we were always worried that if Kork crashed, the bike would take out half a mile of Armco! The chassis was unusual; you could make a quick trail adjustment by changing the front axle position in eccentrics in the front forks, or you could unbolt the steering head and bolt in a different one to lengthen the bike or change the angle.”