“I asked my ‘buddy’, the local doctor, who’s the best orthopaedic surgeon in Holland? His response was ‘we all went to the same university, so we are all as good as each other’. I thought that was an odd answer, but I decided to go with him anyway. Bad choice!”

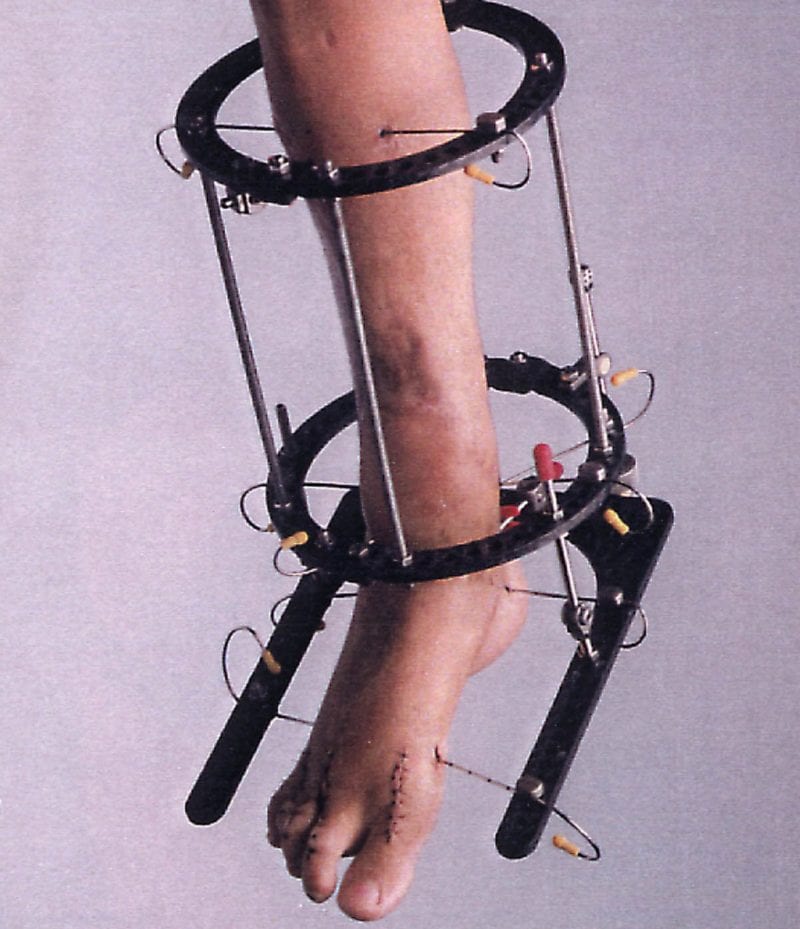

Controversially, the doctor used plates and screws to fix the injury, instead of a rod, and gave Doohan an epidural, instead of a full anaesthetic. “During the op I could feel the power tools rattling through my bones, so I asked to be knocked out.”

And that’s when everything went really wrong. Within hours Doohan’s leg had compartment syndrome, a pressure build-up that cuts off circulation, with potentially disastrous results. “When Costa came to see me the next morning he asked if I could feel my toes and I couldn’t, so I knew something wasn’t good.”

So Doohan went under the knife again. “From there on it got very messy. They cut open the leg from the back of my knee to the ankle and from the top of the foot to the toes. The wound at the back of the leg swelled to about ten centimetres wide. I knew this wasn’t the best scenario for getting back on a bike.”

“I really believe the doctor who operated on me wanted my career over. I heard he said to Schwantz [also hospitalised that weekend] that he felt no sympathy towards us racers because our injuries are self-inflicted.”

There’s no doubt that Doohan did receive horrendous treatment at Assen. “I had to ask to have the bandages changed because the leg was starting to smell like bad meat. The doctor had been speaking with Costa and they got into an argument when the doctor said he would have to amputate the leg if it didn’t improve within 24 hours.”

After that argument the doctor returned to Doohan’s bed in an agitated state and ripped off the dirty bandages, pulling away a lot of flesh. “I was in a fair bit of pain there,” says Doohan with characteristic understatement. “They had to stitch the flesh back together and give me couple of bags of blood.”

Costa – who wasn’t allowed to practice in the Dutch hospital – knew there was no time to lose. He booked an air ambulance, ‘kidnapped’ Doohan and Schwantz from the hospital, despite fearsome resistance from the doctors, and flew them to his clinic in Bologna, Italy.

“It was a relief to get out of there; it was a bad place to be. Costa was concerned because they had thinned out my blood so much [in a desperate attempt to improve circulation] that my internal organs were at risk of shutting down. That was the first barrier he had to cross – to get my general health into a stable condition – then he could see what he could do with the leg.

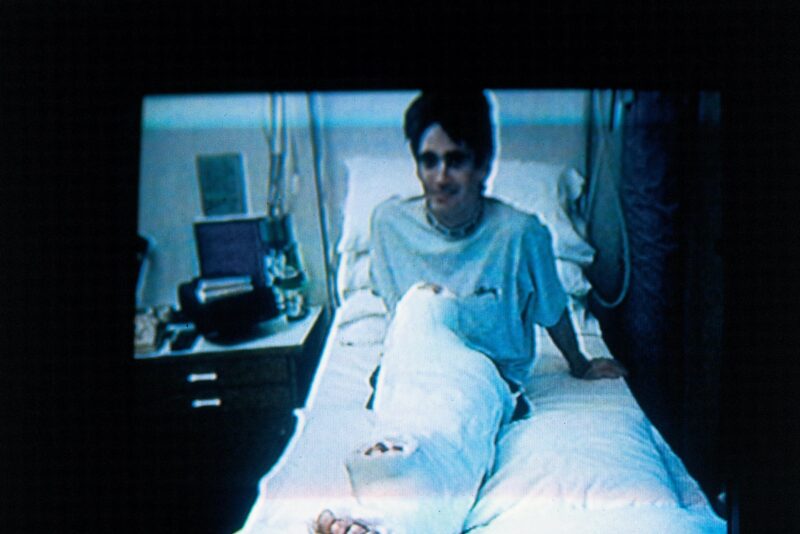

In July 1992 Doohan appeared on TV with his legs sewn together. He wasn’t a well man

Doohan Archive

“It was a dark time – Costa couldn’t speak English, I couldn’t understand Italian and the other doctors weren’t saying anything – but I was just looking forward. I also knew that motorcycle racing does have its downsides, so it wasn’t really a surprise to be in that position.

“I guess I was a bit naïve and not willing to accept that I might lose my leg and never ride again. The only thing that kept me going is that I wanted to get back out there and try to retain the title lead.”

At first Costa prescribed daily visits to a hyperbaric chamber to increase the amount of oxygen in Doohan’s bloodstream. But the leg was still dying.

“I was just agreeing with things because I wanted to get back on the bike… there were numerous operations – I lost count of how many”

“After a week I noticed a lot of very black skin. The doctors took a spoon-type instrument and started removing it until they got down to the tendons and bones and the metal plates and screws. I guess that’s when reality set in – that this was going to be a long road to recovery. But I still wanted to keep pushing.”

Costa finally decided there was only one option: use the blood supply from the left leg to keep the right leg alive. So he sewed the legs together.

“It sounds pretty barbaric and it hadn’t been done for quite a while. Normally when they did that they bolted the legs together, but Costa plastered them together because bolting them wouldn’t be good for getting back in a hurry. It was a bit of a shock, to be honest. I was just agreeing with things because I wanted to get back on the bike. But looking back I wouldn’t change a thing. Working to get back as quick as possible was what kept me going – if I’d been sitting around in hospital for six months it would’ve done my head in.

“Throughout that period there were numerous operations – I lost count of how many – and they were long ops. This one was a success, but it wasn’t pretty, they never were.”