Armco (the name derives from the American Rolling Mill Company) became a serious problem in the early 1970s after Formula 1 drivers demanded crash barriers to prevent out-of-control cars launching off the track with potentially fatal results for them and for spectators. For bike racers, however, the cold steel rails were every bit as dangerous as a dry-stone wall on the Isle of Man. One step forward for car racers was one giant leap backwards for bike racers.

“At one of my first GPs I remember a British rider called Rob Fitton hitting the Armco at the Nürburgring,” says Chas Mortimer. “It nearly took his leg off and he bled to death because there was no one around to stop it.”

Although bike riders lobbied circuits and organisers they had little chance of being heard.

“We were second-class citizens because the cars pulled in more punters,” adds Mortimer. “The other problem was that the organisers were a law unto themselves. They were a lot of terrible men who just weren’t interested. They’d say, on your bike, mate. There were worse places than Monza – Salzburgring was the worst because the track was completely ringed by barriers.”

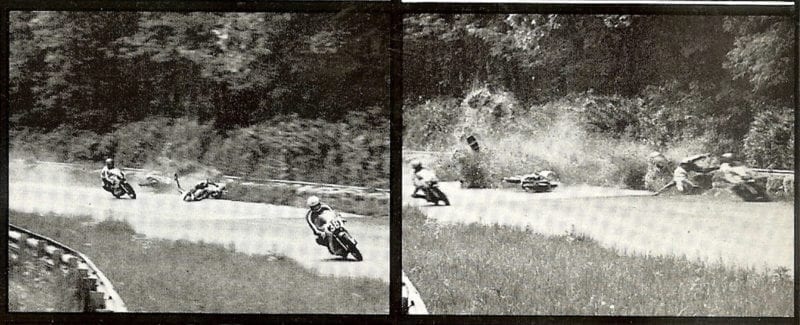

In 1977 the Salzburgring was still encircled by Armco when a massive Monza-style pile-up left one rider dead and several seriously injured, including 1982 500 World Champion Franco Uncini, who is now MotoGP’s safety officer.

Although safety didn’t improve overnight, perhaps Monza was the start of the long road towards today’s much safer circuits. But while some venues did start removing the Armco and installing runoff areas, it was a slow process.

“At Mugello in ’83, the circuit took out the fencing, then told us, ‘Right, your hay bales are here, so go and put them out’”

“For many years I pushed very hard to get organisers to take out the f**king barriers,” says 15-times world champion Giacomo Agostini. “I think the Monza crash did make everyone realise the barriers were bad, but the real reason they were removed was that Formula 1 also realised the barriers were dangerous because they could break fuel tanks and cause fires. Finally people understood they must take out the barriers, but it happened very slowly.”

By 1982 the riders were so fed up with lack of progress that they hired former racer Mike Trimby – now general secretary of MotoGP teams’ association IRTA – to fight for their rights.

“By the time I arrived there was more run-off, but this was before gravel beds, so they had catch fencing, which the car guys wanted to slow the cars down,” says Trimby. “The problem was that the fencing was held up by wooden posts – 500 rider Michel Frutschi was killed by one of the posts at Le Mans in 1983. It was like planting trees around racetracks!

“We had loads of arguments with circuits. We ended up removing a lot of catch fencing ourselves. What we wanted was something that would gradually collapse to slow riders after they’d crashed, which meant good old hay bales. I remember at Mugello in ’83, the circuit took out the fencing, then told us, ‘Right, your hay bales are here, they’re on that tractor over there, so go and put them out’, which we did – us and the riders.’

Bit by bit the riders began to have more of a dialogue with the organisers. “Once IRTA was launched in 1986 we had a formal voice. The other turning point was 1992 when Dorna came in. The deal with them was that we didn’t have to race anywhere we didn’t want to race. Now, when someone like Hermann Tilke [creator of Sepang, Shanghai, Austin and other tracks] designs a new circuit, they incorporate what we want for bikes. The situation can never be perfect but it’s about as close as it can get.”

A few weeks after Saarinen’s death, Yamaha published its own (rather hurried and lightweight) investigation into the Monza accident. The report concluded with a statement that reveals how differently danger was perceived in those days – you won’t find Valentino Rossi’s team boss discussing the necessity of danger in bike racing.

“Motorcycle racing will always involve an element of danger,” said the report. “It may be said that danger is necessary to bring out the qualities of a champion when man and machine are striving for the ultimate performance. But unnecessary and senseless danger can, and should be, eliminated as a duty to the competitors.”

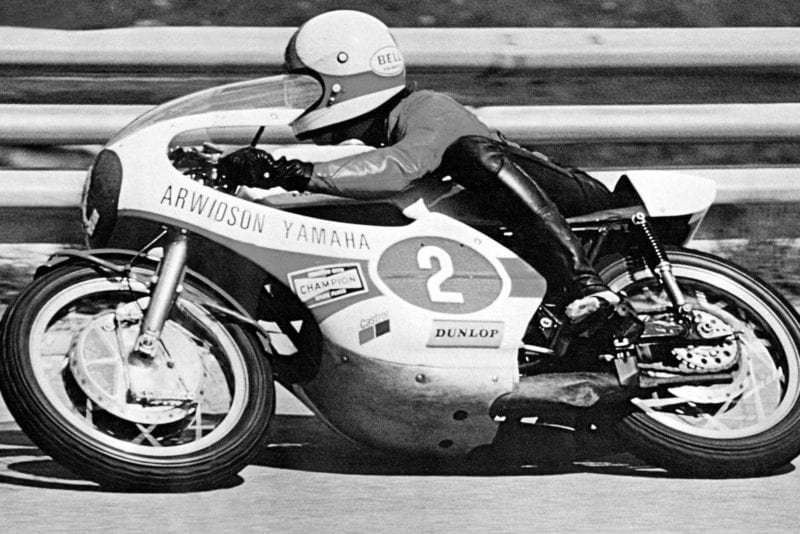

Saarinen took the brand-new 0W19 to victory at Paul Ricard and Salzburgring

Yamaha

The genius of Jarno

Jarno Saarinen was a genius, a game-changer and all set to become an all-time great. He had learned to slide bikes as a champion ice racer, so he brought a whole new way of riding to GP racing. His skills inspired Kenny Roberts to do what he did: drag his knees and ride sideways.

“I started hanging off at Ontario Motor Speedway in 1972,” recalls Roberts. “The track had this horseshoe where I felt so uncomfortable, like I was going to crash. So I watched Jarno – he leaned off the bike with his knee out, so I leaned off and all of a sudden I didn’t have that bad feeling.”

Finnish ice racers like Saarinen made an earlier impact in GPs than American dirt trackers like Roberts and Freddie Spencer. During Saarinen’s era there were plenty more Finns in the GP paddock, including GP winners Tepi Lansivouri and Pentti Korhonen.

Saarinen studied mechanical engineering at university and was known for his meticulous machine preparation. He thought very hard about how to go faster, using both riding technique and machine technology. He was famous for positioning his handlebars at an unusually steep angle, which he claimed helped him to control slides. In little more than one season – between September 1971 and May 1973 – he won 17 GPs across the 250, 350 and 500 classes.

And what if Saarinen had lived?

Bike racing might have had a very different look for the next half decade if Saarinen hadn’t perished at Monza.

The brilliant Finn was running away with the 1973 500cc world championship when fate intervened, so he was already set to make history by winning the first two-stroke 500 crown. His death prompted Yamaha to withdraw from racing, so history was deferred and the two-stroke had to wait another two years before it conquered the premier class.

His passing poses several other questions. If he had lived, would Phil Read have won the 1973 and 1974 500 world titles on the MV Agusta? Possibly not, because the MV four-stroke was being rapidly overtaken by Yamaha’s considerably faster two-stroke.

And if Saarinen’s star had still been in the ascendance would Barry Sheene have won his two world titles in 1976 and 1977? And if Yamaha had had all the riding talent they needed, would Agostini have signed for the factory in 1974 and won his final world title the following year? And would Kenny Roberts have come to Europe in 1978?

It’s all ifs and buts, but there’s no doubt that losing a genius rider at a relatively young age had multiple ramifications for GP racing.