The NR did nearly make it into the points at Assen in 1981, until the ignition cruelly failed on the final lap. By this time Honda was getting desperate, even taking some NR parts to be blessed at a Buddhist temple in Japan, in the hope of some divine intervention.

“I was having a lot of long talks with Iri-san, [Irimajiri],” recalls Gerald Davison, boss of HIRCO (Honda International Racing Company), which was established to run the NR project. “Half joking, I told him he should send the NR people to a temple and tell them to really reflect on what they’re trying to do. The very next day he did just that! A fleet of minibuses took 40 of us to a Buddhist temple. We also took along some bits of the bikes that would receive blessings. So we arrived at this beautiful place, up a forest-clad mountain, with dancing girls and music. It was all pretty spectacular.”

However, divine intervention came there none. By now some Honda people already knew their goal of trying to beat the dominant two-strokes with a four-stroke was hopeless. These included engineer Youichi Oguma, a former racer and road tester, who had played an important part in the development of the CB750, the original superbike.

“I told the bosses that the NR was impossible,” says Oguma, who managed Honda’s GP effort from 1987 to 1993. “I said we must use our two-stroke motocross technology. This was fantastic technology, because we had dominated domestic titles and world championships with our two-strokes. Now we could use this knowledge for road-race bikes, it was very convenient.”

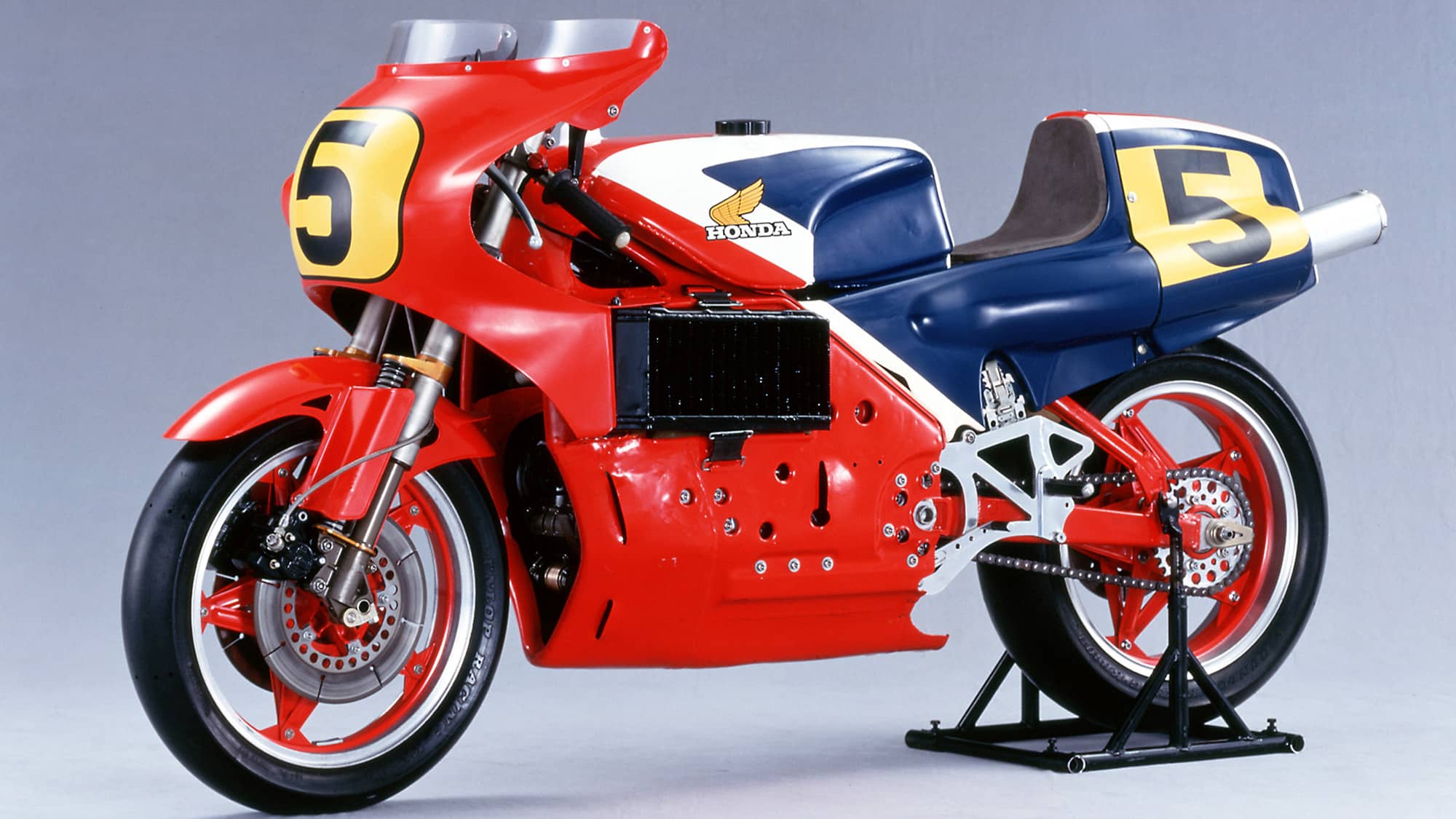

The 1980 NR500, with conventional tubular steel frame, made by British chassis designer Ron Williams.

Honda

In the summer of 1981 Oguma travelled to Europe on a fact-finding mission, examining rival machines at scrutineering and then around the track, taking photos and split times at different parts of circuits. His report dropped onto his bosses’ desk back in Japan “like a bombshell” and Honda was ready to swallow its pride like never before or since.

The man given the huge responsibility of regaining company pride after the NR – which was eventually nicknamed the Never Ready by the media – was Shinichi Miyakoshi, who had worked on Honda’s 1960s GP bikes and created the marque’s first two-stroke racers, the RC motocrossers, which took Honda’s first motocross world title in ’79.

Honda had no doubt who it wanted to lead its first two-stroke GP adventure: American superbike rider Freddie Spencer, who had only ridden in two GPs and finished neither of them (not his fault).

At the 1981 British GP, Spencer’s talent had the NR up to fifth place, before the engine expired.

According to legend, the final decision to use a 3-cylinder engine was taken during an enthusiastic drinking session

“The NR was actually fun because it was so unique,” remembers Spencer. “It didn’t feel like a four-stroke. The motor had such a short stroke that it needed so many more rpm to get the horsepower. Its biggest problem was no torque and not much mid-range, though top speed wasn’t so bad compared to the two-strokes. Because it had no torque you had to use a lot of corner speed, so it was always tucking the front – If a bike lacks power, you’ve got to make it up some place else.’

Miyakoshi’s new engine wasn’t as wild as the NR500, but it was still very different from other bikes on 500cc GP grids, because Honda still wanted to do things differently, so he flew to the USA to convince Spencer and his tuner Erv Kanemoto that his creation would be a winner.

“Erv and I were sitting in a room with this big box on the conference table,” Spencer recalls. “We were wondering what was in the box when Miyakoshi comes in and opens it up. Inside there’s this three-cylinder motor. You should’ve seen the look on Erv’s face! It wasn’t anything like what the other factories were racing, then Miyakoshi explained his theory about how the NS was lighter, narrower and so on.’

The first task in building any race bike is deciding the basic engine configuration, because that’s the heart of the machine. Miyakoshi sketched a square-four, a V4 and a V3. According to legend, the final decision was taken during an enthusiastic drinking session involving Miyakoshi and Oguma. Both men had the same idea, the three-cylinder made the most sense.

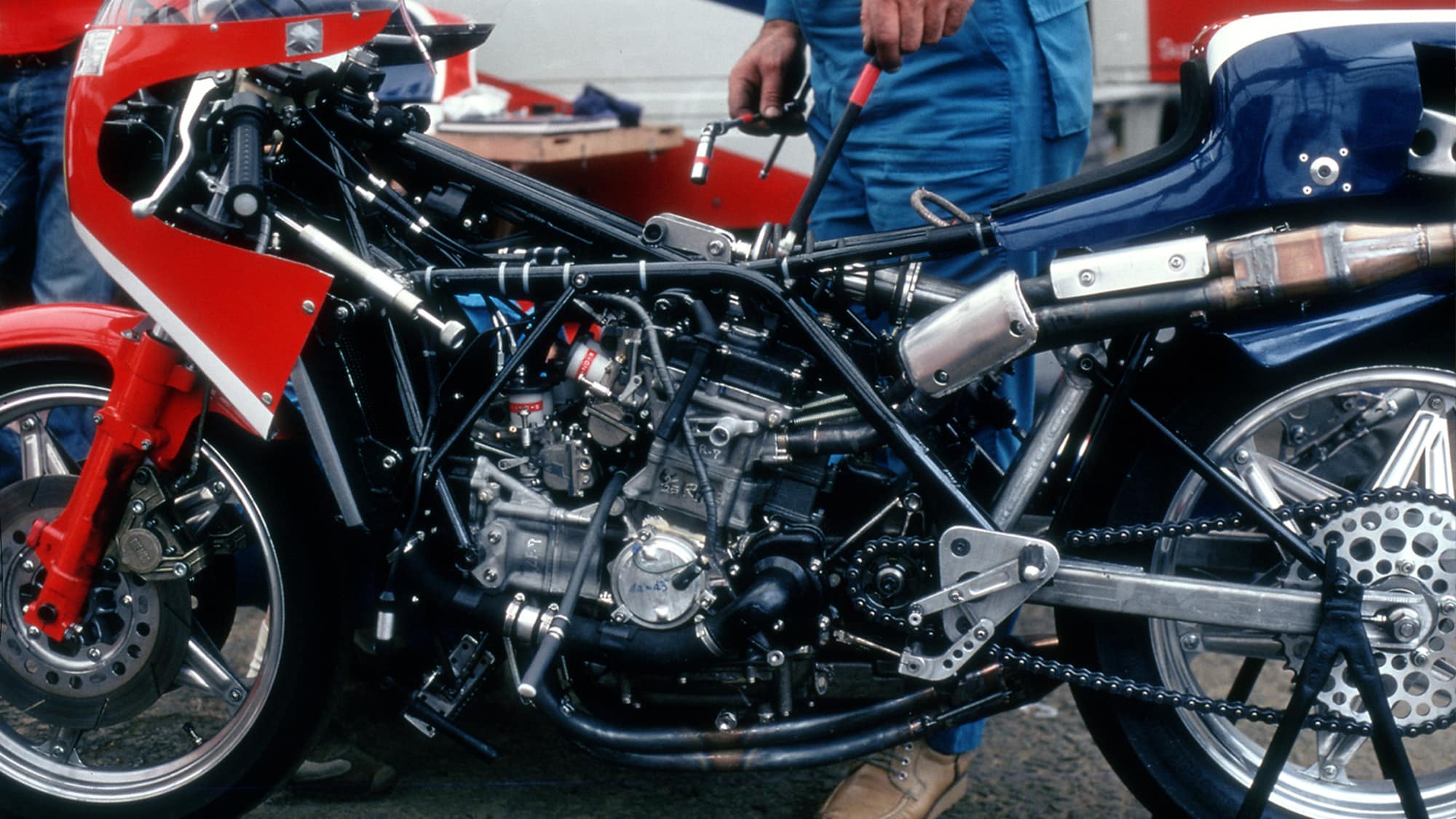

The final NR500, with full carbon-fibre frame. The bike was exhibited at the 1983 Tokyo motorcycle show and never raced.

Oxley

“All the other engines were too big, too heavy or too complex,” reckons Oguma who, during his European visit, had noticed how twin-cylinder 350cc GP bikes were very nearly as fast as the 500 fours at some tracks.

The NS500 was arguably the first modern MotoGP bike, because it prioritised overall performance over outright engine performance. Its four-cylinder rivals – Kawasaki’s KR500, Suzuki’s RG500 and Yamaha’s 0W61 – were fast but unwieldy, their chassis and tyres overpowered by their engines. Miyakoshi and Oguma acknowledged that corners are as important as the straights. More so, in fact.