Even four-strokes with traction control can bite and when they do things can still go badly wrong. Although run-offs are wider than ever and riding gear is safer than ever there are two main worries for the rider once he’s down – getting hit by another bike and getting hit by his own bike. Sadly, these two predicaments are impossible to mitigate.

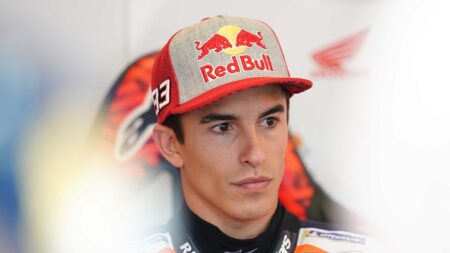

It was Márquez’s misfortune to be struck by his motorcycle when he tumbled through the gravel trap at Jerez’s Turn Three in July. That was what broke his right upper arm.

The humerus bone isn’t a good one to break, but Márquez’s biggest problem isn’t the fracture but a malunion of the bone. That means the two parts of the bone didn’t grow together correctly, due to an infection in the fracture site and due to his abortive comeback, just days after the first operation to plate the fracture.

Last week’s third surgery – using bone grafts to fix the malunion – came almost exactly four months since that second op, so why didn’t surgeons react sooner? Because they have to wait and monitor bone growth. Only once they’re certain the bone isn’t healing properly do they go in again.

The problem with racers and injuries: they push themselves too hard and it’s not easy to tell them to stop.

When will Márquez be back on a MotoGP bike? No one knows, not even his orthopaedic surgeons, because his recovery could be better than expected or worse than expected. One learned surgeon will give you an opinion and another will give you a second opinion. In other words, anything you read on this subject at the moment is pure speculation.

But we can get an insight into Márquez’s journey through the story of Repsol Honda’s first multiple world champion, who travelled a similarly rocky road in the 1990s.

Mick Doohan broke his right leg at Assen in 1992, when he was 27-years-old, the same age as Márquez is now. The botched surgery that followed very nearly ended his career. Doohan was able to continue racing, but only by sentencing himself to a grisly few years of pain and suffering, with no guarantee of success at the end of it.

Doohan regains control just too late to avoid the straw bales, Laguna 1993. He went down hard

Doohan sustained a distal spiroid displaced fracture of the tibia, which shouldn’t have been a huge problem, but the local surgeons messed up the operation, during which they pinned and screwed the bone back together. Their poor workmanship caused compartment syndrome, which starved the limb of fresh blood. Within days the leg had started to rot.

Incredibly, Doohan was racing again two months later but the fracture site had become infected and the infection wouldn’t go away. After the 1992 season surgeons went back in to remove the pins and screws in the hope of clearing out the infection.

Getting rid of the metalwork exorcised the infection, but one problem fixed was another caused. The Aussie was determined to do everything he could to get fully fit for the 1993 season, so he hit the gym, hard. So hard that he bent the tibia, because the bone had been weakened by the removal of the metalwork.