“You’ve got to have a rapport, because if you’re in a tense situation and the rider says something wrong about the bike then the crew chief will be in deep shit. You’re always going to have disagreements. I knew that and it wasn’t a problem for me. Many times I could easily have thrown a fit and said, ‘I need a new guy’. But everybody is human and makes mistakes. Then you get the guys that blame their problems on the crew chief – Max Biaggi was a lot like that.”

Carruthers had won the 250cc world championship a few years before he started working with Roberts, so he knew what he was talking about. Many of the greatest crew chiefs are former riders, because it’s easier to understand what a rider is talking about if you’ve been in that same situation. Burgess, for example, raced at a high level in Australia.

“I think it helps if the crew chief has raced,” Roberts adds. “It’s not the end-of but it probably adds a bit more credibility when they’re talking to the rider. If the rider respects the guy he’s working with that makes a hell of a difference.

“A lot of times Kel knew what I was going to say before I said it, but he let me say it anyway. Kel and I spent a whole lot of time together, so if you don’t like the guy it’s impossible. We got on and I had faith in him, although he did put my brake pads in backwards at Assen in 1981. I was on pole and it was the first grand prix the managing director of Yamaha had ever visited. I didn’t get to start the race, but you’ve got to be able to laugh that stuff off.”

Yamaha trusted Carruthers so much that its engineers gave him freedom to do pretty much whatever he wanted to the bikes – things that would never even be contemplated now.

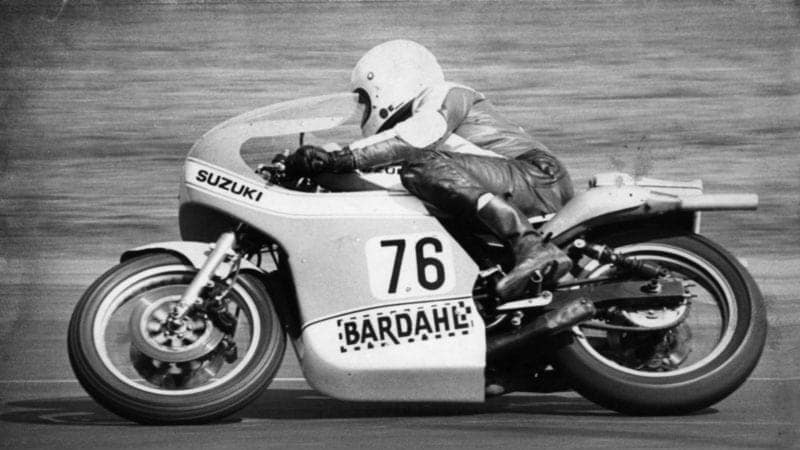

Esteban Garcia (on Viñales’ left) after victory in the 2021 Qatar GP

Yamaha

“I had a lathe and a milling machine in the back of the truck,” Carruthers says. “One year the new 500 arrived, and it was useless, so I machined a millimetre off the bottom of the cylinders, modified the cylinder heads and changed the port timing. Another time the rotary-valve inlet timing was all wrong, so they sent complete 360-degree discs and I cut them myself. Once they even let me cut the front end off a 500 chassis and weld it back at a different angle!

“When I first went to Europe with Kenny we were basically on our own; we had one Japanese guy who basically just took notes. The Japanese engineers told me they were learning from me what it was all about. It eventually got to the stage where they had learned a lot, they became more involved and the bikes got better.”

After Roberts retired from racing at the end of 1983 Yamaha occasionally asked him to help younger riders who were getting lost with all the complexity and responsibility of top-level racing.

“Yamaha came and asked me to talk to this 250 rider whose head was all screwed up. This guy told me, ‘I’ve got this problem with the truck and with this mechanic’. I told him, ‘They’re not your problem, your problem is that you’re not fast. You’ve got to forget about everything else and start worrying about being fast.”