Reigning F1 champ Max Verstappen raced bikes when he was a kid, Fernando Alonso has ridden a Honda RC213V MotoGP bike at Motegi, Kimi Räikkönen runs a factory Kawasaki motocross team, Sebastian Vettel is a keen collector and rider of classic motorcycles, Red Bull engineering genius Adrian Newey got his first job in F1 because he turned up for the interview aboard a 1970s Ducati 900SS and Mercedes boss Toto Wolff has spectated at the Isle of Man TT.

The first seven-time F1 king Michael Schumacher got seriously into bikes during his sabbatical from F1, racing a Honda Fireblade in the German superbike championship, with some success. He was forced to stop due to a neck injury.

Damon Hill, 1996 F1 champion with Williams and son of twice 1960s F1 champ Graham Hill, grew up wanting to emulate his hero Barry Sheene on motorcycles. He started out racing in a one-make Kawasaki series and graduated onto a Yamaha TZ350, winning the 1984 King of Brands title, but he struggled to get sponsorship and had little choice but to switch to four wheels.

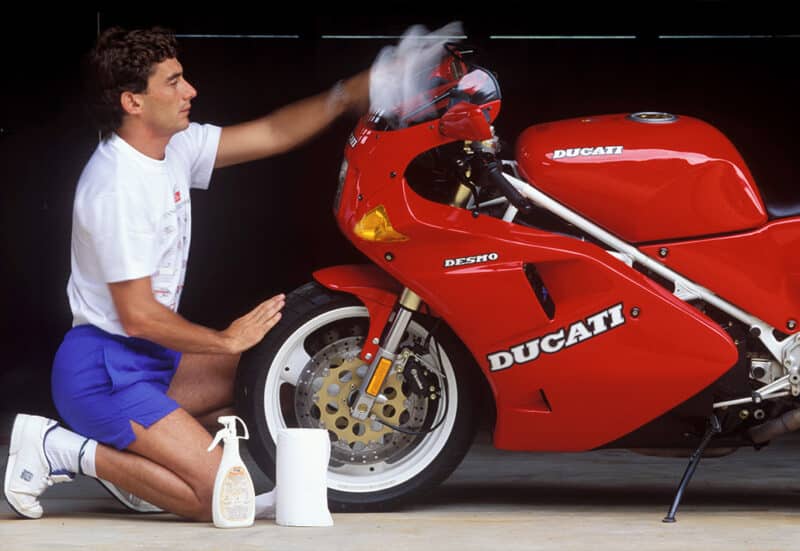

Senna looking after his Ducati 851 at home in Brazil

Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

John Surtees moved seamlessly from winning motorcycle world titles with MV Agusta to winning the F1 crown with Ferrari. He saw the similarities in his job as a rider and a driver. “The relationship you create with a piece of machinery is something very special,” he told me. “In a way it talks to you, so the important thing is to understand what it’s telling you.”

Mike Hailwood graduated from bikes to cars, just like Hill and Surtees, but with less success – Mike the Bike won nine motorcycle world titles and scored two podiums in F1. Funnily enough, he believed F1 to be more dangerous than bikes, but that was in the era when F1 cars too often turned into fiery death traps.

The great Ayrton Senna was a big fan of motorcycles and was close to Claudio Castiglioni, who, with his brother, saved Ducati from bankruptcy in the 1980s. Senna owned several big red v-twins, most famously an 851, Ducati’s first world Superbike machine.