Dirty money in MotoGP? It’s nothing new

For many decades the wheels of motorcycle racing have been oiled by money emanating from unsavoury sources

Aramco is linked as a sponsor of the VR46 MotoGP team next season, but it's far from the only time controversial funding has helped racing

Jose Breton/Pics Action/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Now that the initial hoo-ha over VR46’s alleged multi-million pound sponsorship deal with Saudi Arabia’s state-owned Aramco oil company has calmed down, perhaps this is a good time to take a long look at motorcycle racing’s historic relationship with dirty money.

The fact is that most motorcycle racers will do just about anything to go motorcycle racing. It’s a tired analogy but it bears repeating – bike racers are junkies and like any junkie they’ll do anything to get their next fix.

For example, during Britain’s 1980s proddie racing boom the paddocks at Brands Hatch, Snetterton, Cadwell and elsewhere were full of stolen motorcycles, with racing numbers in place and engine and chassis numbers mysteriously missing. So this was motorcycle racers robbing their brother and sister motorcyclists to score their weekend fix, just like a heroin addict stealing his mum’s purse.

When the media asked Valentino Rossi about the Aramco deal during last weekend’s Spanish GP the nine-times world champion artfully dodged every question, then offered these words, perhaps by way of explanation. “We are motor sport addicted.” Like the addict apologising to his mum for nicking her purse.

So what kind of dirty money has helped turn the wheels of racing motorcycles over the decades? Perhaps we should start at the top, or rather at the bottom, in the absolute pits.

During the 1930s Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party were enthusiastic supports of all kinds of motor sport – especially record-breaking – from Mercedes and Auto Union in cars to BMW and DKW in bikes. This was pure propaganda – the political arm of advertising and marketing – to show the world that Aryan engineers were the cleverest and Aryan racers the bravest.

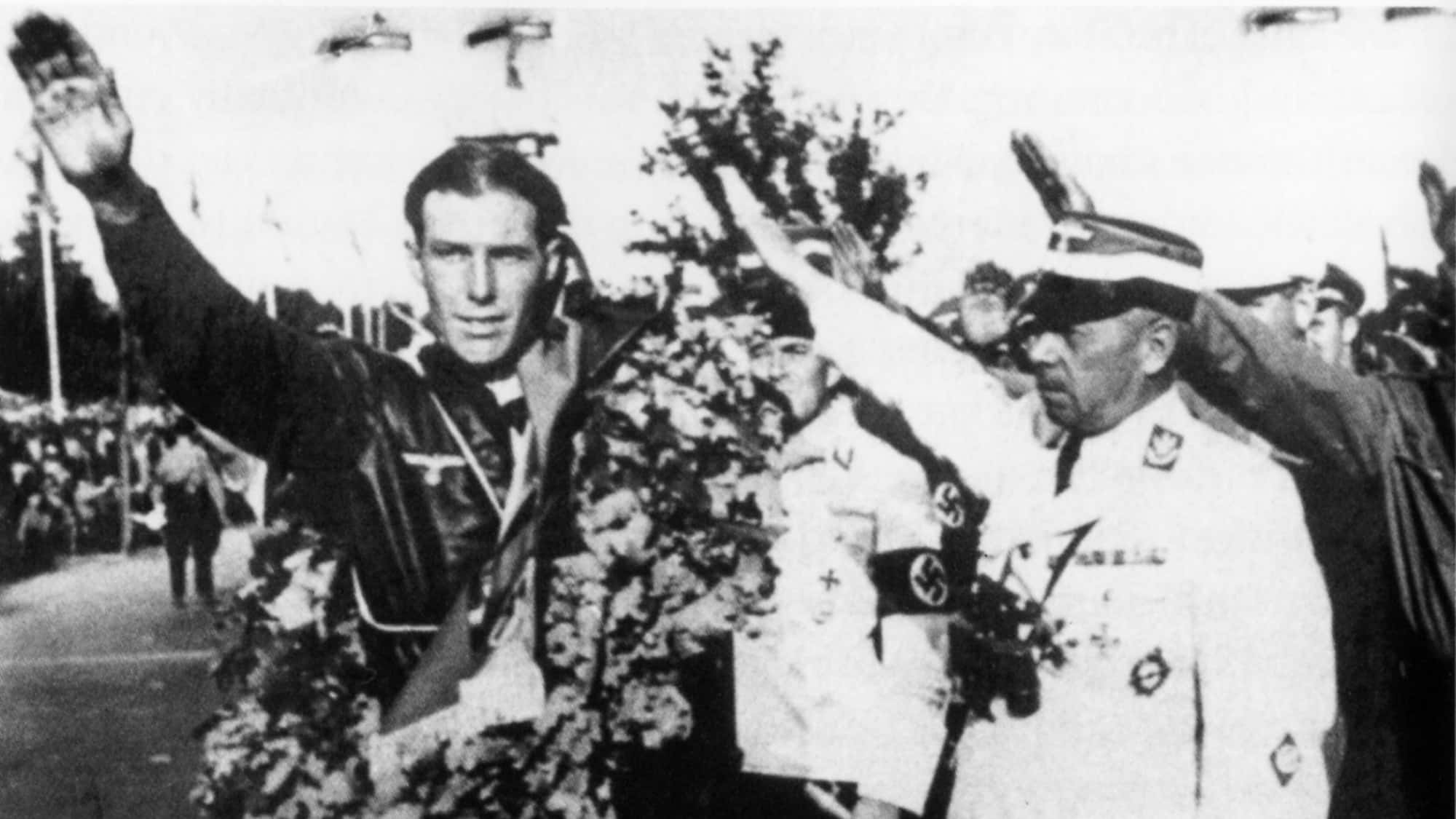

BMW rider Georg Meier and Korpsführer Adolf Hühnlein, leader of the Nazi motor corps, celebrate another race win in the 1930s

“Absolute records on land and water, that fits our propaganda,” Hitler told the German manufacturers. “You will have every support.”

Hitler knew the coming war would be a mechanised war, so he established the NSKK (the National Socialist Motor Corps) which trained young men to ride and fix motorcycles and other vehicles. You weren’t even allowed to race unless you were in the NSKK.

The Nazis were so keen on motorcycle racing they had Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels attend the 1935 FIM annual convention in Berlin, accompanied by Korpsführer Adolf Hühnlein, leader of the Nazi motor corps. Nowadays Hühnlein would be called a sponsorship liaison officer.

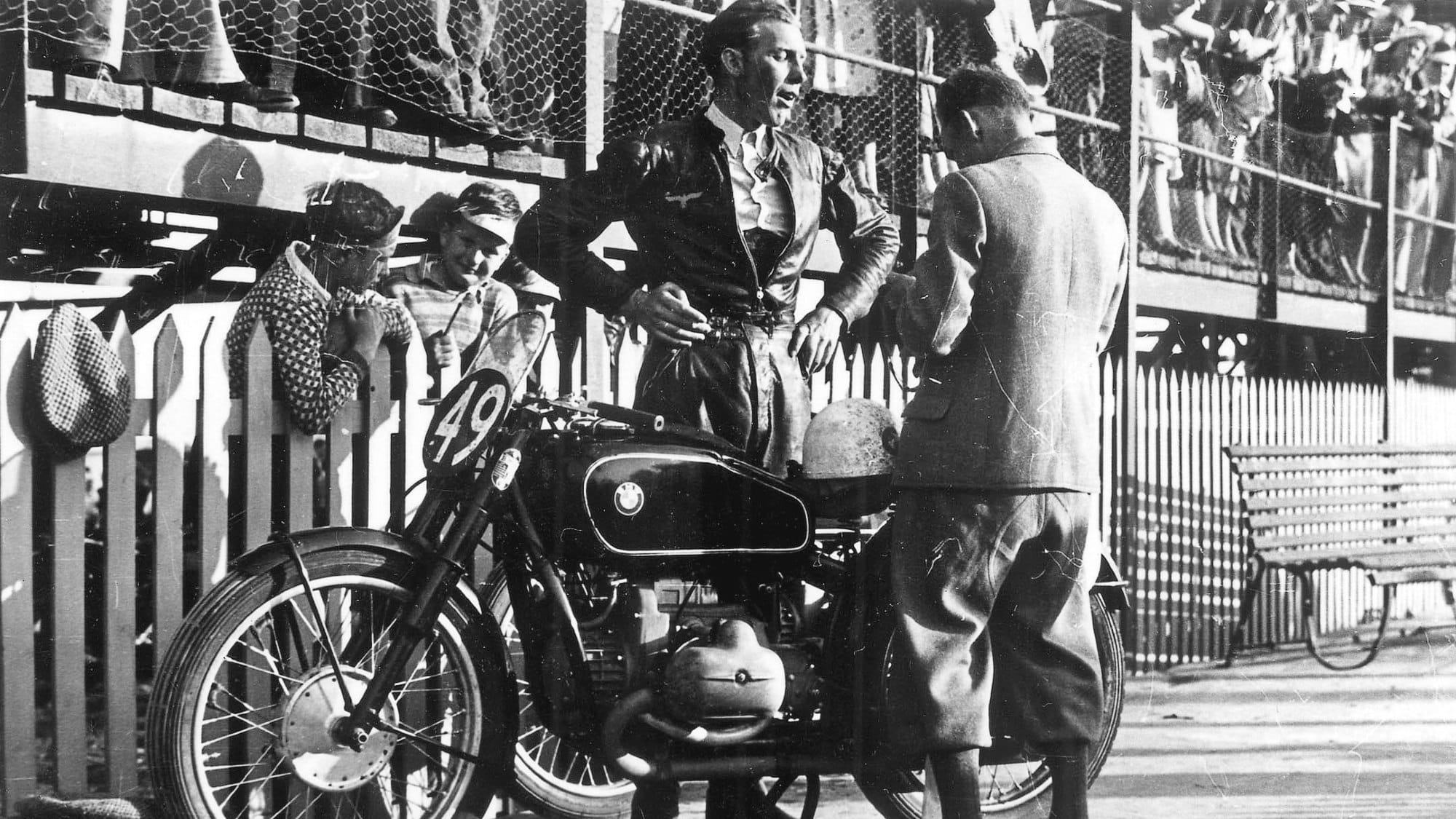

BMW and DKW both won Isle of Man TT races and European championships (the forerunner of today’s world championships) with Hitler’s support. In June 1939 Georg Meier stunned Norton by winning the Senior TT aboard a supercharged BMW twin, but he lost that year’s 1939 500cc European championship to Italian Doriano Serafini riding Gilera’s supercharged four, blessed by Italy’s fascist leader Benito Mussolini.

The Gilera four was christened the Rondine – Italian for swallow – after the CNA plane that had escorted Mussolini’s Brownshirts when they marched on Rome to take power in 1922. (Incidentally the plane was powered by a British ABC 350cc flat-twin, not dissimilar to the Douglas flat-twin that inspired BMW’s flat-twin.)

“We christened the bike Rondine for good luck,” said the bike’s creator Count Giovani Bonmartini, a friend and keen supporter of Mussolini. “CNA was the only aeronautical company that dared fly its airplanes with the fascists on the march on Rome. This airplane took off in the presence of Il Duce and was named Rondine; a fast and strong bird that’s capable of escaping birds of prey because of its flying ability. Don’t you think that this is quite a suitable name for a motorbike?”

Meier (note sponsor’s logo on his leathers) prepares for his winning 1939 Senior TT ride aboard his supercharged BMW

On a much lesser and occasionally more amusing scale are the nefarious dealings of some grand prix racers during the decades following the establishment of the world championship in 1949. Most racers never have enough cash and some are prepared to go great lengths to raise finance.

“We had no money, so you had to be a bit of a rat, otherwise you wouldn’t survive,” said Aussie Jack Ahearn, winner of the 1965 Finnish 500 GP. “We had to get a pound or starve.”

Most famously colourful Italian Walter Migliorati financed his 1980s GP campaign through his, erm, import/export business, because Suzuki’s finicky RG500s didn’t look after themselves. In 1984 Migliorati was on the road between GPs when he was stopped at a European border crossing. Customs officials found half a kilo of cocaine and two kilos of hashish in his camper. He did a long stretch for that crime and never raced again.

That kind of import/export business was nothing new. In the 1960s most GP privateers knew there was a dodgy garage in London where they could take their race vans to get ‘fixed’ to raise some extra cash.

“I was told that if I went to this garage before I went to Europe they’d change the driveshaft on my Ford Thames van,” recalls New Zealander Ginger Molloy who finished second to Giacomo Agostini in the 1970 500cc world championship. “Obviously they were welding drugs in there, but I hadn’t travelled halfway around the world to do that.”

However, Molloy and many others did keep themselves going with much less naughty import/export work, just a little low-key smuggling, like buying 50 bottles of Bacardi and a few thousand cigarettes in Spain and selling them for a handsome profit in the UK, so long as the customs didn’t find the contraband buried under the bikes in the back of the van. Molloy remembers one Channel crossing returning from racing on the Continent during which one of his helpers was very sick, so they laid him atop the contraband, which discouraged the customs officers from taking a closer look.

Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels and Hühnlein attend the 1935 FIM annual convention in Berlin

And then of course there’s the tobacco money that fuelled the GP racing boom from the 1970s until the industry was banned from advertising through sport at the end of 2006.

During the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s much of the MotoGP grid was financed by the profits of the tobacco industry: Marlboro, Rothmans, Lucky Strike, Camel, Fortuna, Cabin, Parisienne and the rest. Riders, team bosses and many others grew fat on this money, which was far from clean. During the 20th century tobacco killed around one hundred million people, more than the total casualties of the First and Second World Wars.

Rossi’s alleged Aramco deal has raised a stink because of Saudi Arabia’s appalling human rights record and its currently involvement in the Yemeni Civil War, which has so far claimed the lives of 230,000 people, many of them women and children. It should be noted that the Saudi military has bought weaponry from many countries, including the UK and USA.

Aramco had many other sports sponsorship projects underway, from Formula 1 to Saudi’s first-ever women’s golf tournament. The company has a market capitalisation of around $1.88 trillion, slightly more than the GDP of Russia.