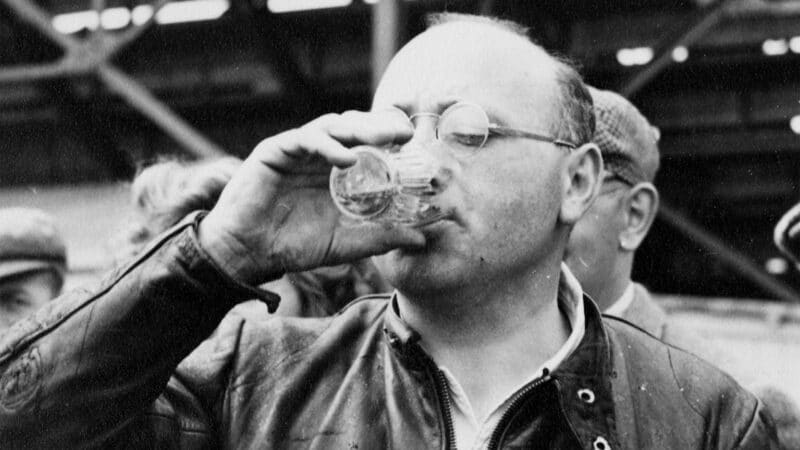

You would struggle to find anyone less like a modern-day MotoGP rider than 39-year-old Daniell, who looked more like a pub landlord than a motorcycle racer: stocky, slightly overweight and always wearing thick spectacles, without which he was helpless.

Indeed he was so myopic he wasn’t allowed to fight in the war. Before WW2 he ran a motorcycle shop in south London, so when he was turned down for military service he used his mechanical know at Napier, which made aero engines for the Hawker Typhoon and Tempest.

Graham was something very different. A lean, keen and dashing RAF bomber pilot who is still the oldest MotoGP title winner, at 37 years old.

The Merseysider was decorated twice during the war. He received the Distinguished Flying Cross following a raid on Nazi U-boat submarine pens in France, when a Lancaster flying immediately below his blew up. The force of the blast flipped Graham’s plane onto its back, dumping him out of the pilot’s seat.

“All of a sudden we were upside down and hurtling towards the ground,” recalled Graham’s navigator Bill Bissonnette. “As we flipped over, Les spilled into the centre of the craft and I thought our end had come. Les was scrambling about, draped over the throttles and trying to reach the stick. Finally he got his left hand on it and managed somehow to pull us out of it.”

No wonder Graham was so good at handling a motorcycle. And he would’ve won the 1949 500cc crown much more easily but for disaster at the opening race…

Round one

Isle of Man Senior TT

Friday 17th June 1949

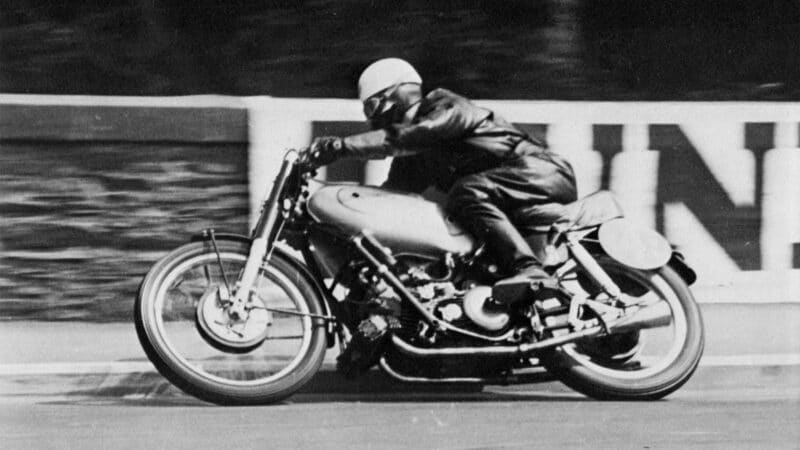

Harold Daniell – too short-sighted to fight in the Second World War – celebrates winning the first-ever MotoGP championship race, on the Isle of Man in June 1949

Ivar de Gier/Archives A Herl

Bike racing’s new world order began on 1st June at 4.45am, when Graham was among the first to plunge down Bray Hill during the first MotoGP practice session, aboard his factory rider AJS E90 Porcupine twin.

Graham was on a mission in the seven-lap race, which went on for more than three hours. He led until half distance, when factory Moto Guzzi rider Bob Foster took the lead. Foster was 57 seconds clear of Graham when his very quick twin broke its gearbox on lap six. That put Graham into the lead, well ahead of Daniell, for what would surely be an easy last lap.

But it wasn’t to be. The AJS stopped at Hillberry, with just 1.75 miles of 264 remaining. Its Lucas magneto armature shaft had broken; a problem that went unsorted for several years. Graham pushed in to finish tenth.

Thus Daniell won the first 500cc world championship race, by one minute and 33 seconds, from Norton team-mate Johnny Lockett.

Round two

Bern, Switzerland

Sunday 3rd July 1949

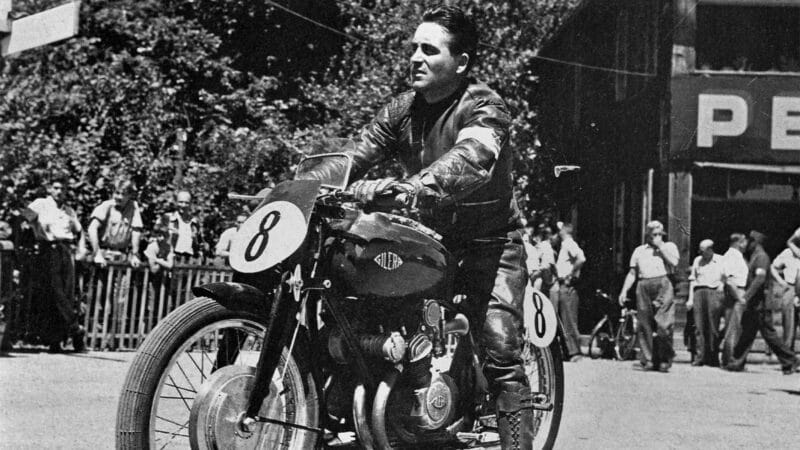

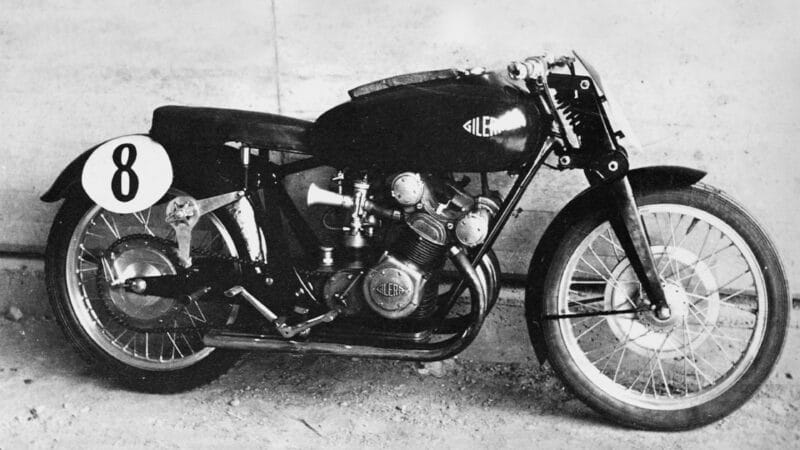

Carlo Bandaliro and his Gilera four-head to the start of the Swiss GP. The Italian was nicknamed Bouncing Bandi because he crashed a lot

Ivar de Gier/Archives A Herl

Everything was different at Bern. The throb of Norton singles and the growl of AJS and Guzzi twins was joined by the staccato scream of Gilera fours and supercharged V12 Ferraris.

That’s right, this was a combined car/bike meeting around the scary-fast, tree-lined Bremgarten circuit (where legendary Guzzi rider Omobono Tenni had lost his life the previous year), so the bikes shared the paddock with Ferraris and Maseratis. The car race was won by Alberto Ascari, driving Enzo Ferrari’s first F1 car.

Gilera’s four-cylinder 500 was much faster than the Norton single. Factory rider Arciso Artesiani led the charge and team-mate Carlo Bandaliro might have gone with him if he hadn’t crashed out, leaving Graham to take the lead, chased by team-mate Frend, who also fell.

Graham made up for his TT disappointment by taking the win, a minute ahead of Artesiani, with Daniell third. Thus Daniell led the world championship from Graham and Artesiani. Gilera would live to regret not making the trip to the TT, for reasons of cost.

Round three

Assen, Netherlands

Saturday 6th July 1949

AJS factory rider Graham leads the Dutch TT at Assen, just ahead of Norton’s Artie Bell

Ivar de Gier/Archives A Herl

Nello Pagani had ridden a Gilera Saturno single into fourth place at Bern but graduated to a year-old Gilera four at Assen. The Arcore factory would soon have something else to regret – that Pagani hadn’t moved up sooner.

Nothing could beat the Gileras away from the line, so Artesiani and Pagani led, but it wasn’t long before Graham was with them, riding as aggressively as ever. The 37-year-old liked to use a few tricks, including purposely running wide out of corners to shower his pudding-basin-wearing pursuer with stones.

When one rival complained, Graham replied, “Sonny, when you’ve done as much racing as I have you will understand there’s nothing wrong with my tactics”. Remember, he had been flying a Lancaster only four years earlier.

Graham lost his last-lap battle with Pagani, but took the championship lead.

Round four

Spa, Belgium

Sunday 17th July 1949

The Gilera four, the fastest motorcycle in the 1949 season. Note spring seat and friction-damper rear suspension

This was the first GP to be started with a traffic-light system: red with a minute to go, amber with ten seconds to go, then green. The original nine-mile Spa circuit was mega-fast but lap-one leader was Bell on his Norton, chased hard by Graham and Artesiano.

Graham lost his chance of extending his title lead when he ran up a slip road, then retired with a split fuel tank. That left AJS team-mate Bill Doran engaging in thrilling slipstreaming battle with Artesiani and the factory Guzzi of Enrico Lorenzetti.

All three took their turn in front, Doran finally crossing the line two tenths ahead of Artesiani, the closest finish of the year, with Lorenzetti a second further back in third. Pagani finished fifth to move him into the series lead, two points ahead of the luckless Graham.

Round five

Clady, Ulster

Saturday, 20th August 1949

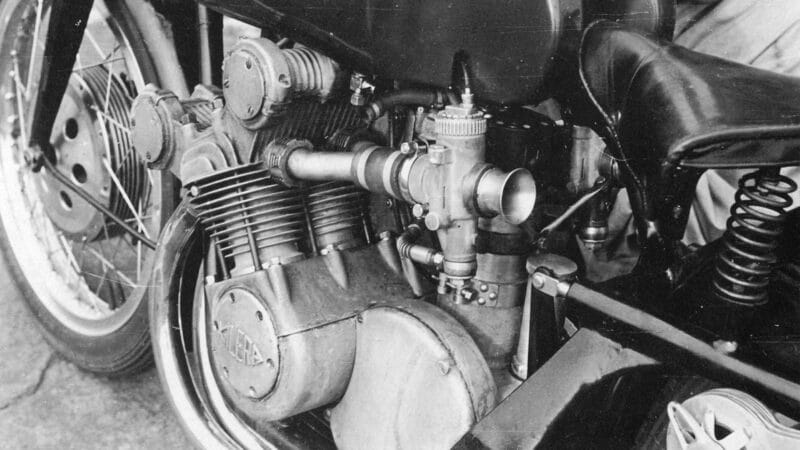

Graham’s AJS Porcupine twin – and now you know why it was nicknamed after nature’s spikiest rodent

Ivar de Gier/Archives A Herl

This was Graham’s race from the first lap and his runaway victory wrote his name in the history books as the first 500cc world champion. Bell and Pagani were second and third, almost two minutes behind the winner.

Guzzi’s hopes of another strong race were ruined when Lorenzetti had to miss the race due to spinal injuries and Foster ran out of fuel, after failing to see his crew calling him in for a pit stop, because his goggles had been crackled by flying stones.

Round six

Monza, Italy

Sunday, 4th September 1949

Graham leads the Italian GP sweeping through Monza’s Parabolica, ahead of Gilera riders Artesiani and Pagani

No surprise that Gilera were out in force for the grand finale. On the other hand, Norton didn’t even bother turning up, fully aware they wouldn’t stand a chance against the fours at super-fast Monza.

The race was a classic Monza slipstreaming brawl, with Graham fighting with the Gileras of Pagani, Artesiani and Bandirola, nicknamed Bouncing Bandi. Once again Bandirola crashed out, while trying a mad move on leader Graham, who he took with him. Meanwhile Pagani romped home to win, eight tenths ahead of Artesiani. Doran completed the podium in a distant third. The final points count had Graham ahead of Pagani by one point in the riders championship and AJS one point ahead of Gilera in the constructors.

The first MotoGP-winning bikes

AJS E90 Porcupine

The AJS twin originally used a supercharged engine, but supercharging was banned after the war, causing AJS big problems

The 120mph Porcupine – christened for the spiky finning on the horizontal cylinders and heads – was conceived during the war as a supercharged engine by Joe Craig, Phil Irving, Matt Wright and others. However, the post-war ban on supercharging demanded a complete redesign, which never happened, so the ‘Porc’ was far from ready for the 1949 season.

Project-leader Wright knew how to transform the 68 x 68.5mm ‘Porc’ from a low-revving, low-compression, high-boost engine with 90-degree valve angle into a higher-revving, zero-boost engine with narrower valve angles and higher-compression. However, AJS boss Donald Heather refused to cough up, so Wright was forced to compromise, working to reduce cylinder-head depth and valve angle without casting all-new heads.

Cooling was a huge problem, so much so that AJS considered casting a cylinder head in silver for better heat dissipation. Inevitably, the budget didn’t stretch that far. Carburation was also a problem, due to the long induction tracts, originally required to damp down the pressure fluctuations of a blown engine.

The first Porcupine engine produced a disappointing 30 horsepower, less than a Norton single, but by 1949 Wright had unlocked an extra 20 horses, just enough for Les Graham – almost certainly the best rider on the grid – to fight with the Gilera fours. The Porcupine continued to struggle after 1949. The problems were finally solved when Jack Williams took over development in 1954, only for AJS to dissolve its factory team at the end of that year.

Some good thinking went into the chassis: a twin-loop frame fabricated with a mix of round and oval steel tubing for better stiffness/lightness ratio, plus telescopic forks and ‘jam-pot’ hydraulic shocks. But Heather’s tightfistedness – he refused to pay for best-quality parts – was a constant hindrance.

Gilera Quattro

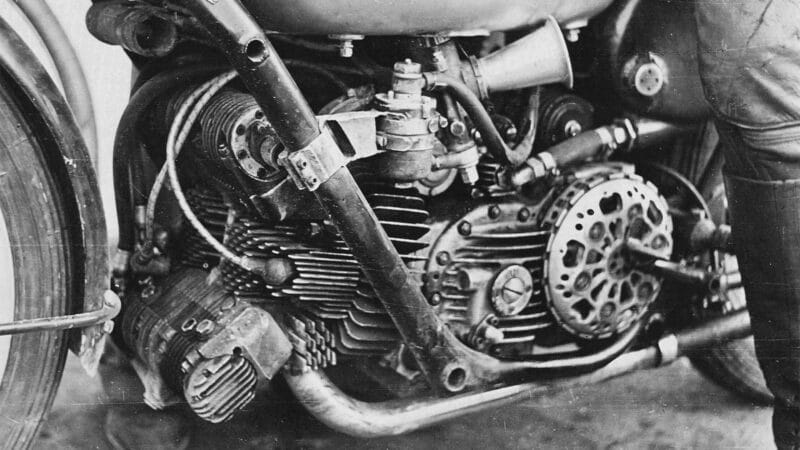

The Gilera four’s engine – the blueprint of all inline-fours was originally created in Rome in 1923

Ivar de Gier/Archives A Herl

The Gilera four won the last pre-war 500cc European championship with Dorino Serafini onboard, but that was in supercharged form. Like AJS, Gilera had to redesign their engine for 1949, but they went much further and did such a good job that their engine became the blueprint for the inline four, which continues to dominate today’s motorcycle market.

Piero Remor, who had designed his first inline four in 1923, created an all-new 52 x 58mm air-cooled engine (the supercharged version had been water-cooled), with cylinders inclined forward 30 degrees (the prewar engine’s cylinders had been canted almost 60 degrees). Cylinders, heads and upper crankcase were cast as one unit and pistons were machined from billets of Duralite aluminium alloy.

The engine made 55 horsepower at 8500rpm, 25 less than its blown predecessor, but extensive use of lightweight materials kept weight down, so the four was lighter than the AJS twin and barely heavier than Norton’s single.

However, Gilera riders paid a price for the lightness. The chassis wasn’t stiff enough, so the bike handled very badly, which is why Nello Pagani started the 1949 season aboard the company’s easy-riding Saturno single.

The four was such a handful at high speed that riders couldn’t hold the engine flat-out down the bumpy seven-mile straight that dominated the Ulster GP’s Clady circuit, thus nullifying their horsepower advantage. There were other reasons for this wayward behaviour. Whereas the British bikes featured hydraulic forks and shocks, the Gilera made do with girder front forks and friction dampers at the rear.

At the end of 1949 Remor quit the factory after a row with Giuseppe Gilera (Remor was as truculent as he was clever) and joined MV Agusta, where he drew MV’s first 500 engine, which was very much like his previous creations. Gilera installed hugely talented engineer and former racer Piero Taruffi as team boss. Taruffi played a major part in the factory’s title success in 1950. Gilera dominated the 1950s until MV got up to speed at the end of the decade.

Norton single

Harold Daniell with his 1949 factory Norton – not much power and very basic suspension. The Featherbed chassis appeared in 1950

Ivar de Gier/Archives A Herl

Norton dominated the 500 class throughout the 1930s until the blown BMW twins and Gilera fours turned up. With supercharging banned, could the venerable single reassert its dominance?

In theory, a single shouldn’t have stood a chance against the twins and fours, but neither the AJS nor the Gilera were anywhere near fully developed, whereas the Norton engine was almost at its peak, 32 years after the Walter Moore-designed engine won the Senior TT first time out in 1927.

Norton technical director Joe Craig led the Birmingham effort during its greatest years, diligently extracting more horsepower from the twin-cam 82 x 94.3mm engine via his painstaking trial-and-error method.

“Joe was no designer,” recalled factory mechanic Charlie Edwards. “He had been left with a very good engine and he patiently and logically developed it.”

Norton’s 1949 factory 500s were in fact 11 years old, last raced at the 1938 TT, but while they were down on power and speed against the multis the difference wasn’t as much as it might’ve been because the single did have its advantages. During practice at each racetrack Craig and his mechanics took up position at a fast section, where the factory riders stopped, the cylinder head was removed and precise combustion readings taken from the head, so the bikes would start the race perfectly jetted. This wasn’t usually the case with the AJS and Gilera.

Like everyone else, Craig had to drastically reduce compression ratio – from 11:1 to 7:1 – to suit the only available 75-octane ‘pool’ petrol. “Little better than paraffin,” he said.

The Norton reached its peak over the following two years, largely thanks to the input of Polish engine expert Leo Kuzmicki and Irish chassis genius Rex McCandless. Kuzmicki used the new concept of squish to increase compression and thus power and tractability, despite the low-octane fuel.

McCandless created the seminal, so-called Featherbed chassis, which Norton bought from the Irishman in 1950, allowing the factory to ditch its obsolete ‘garden gate’ frame. It was Daniell who gave the seminal chassis its nickname because it gave a ride like a feather bed.

With new boy Geoff Duke onboard in 1950, Norton would’ve won the 500 world title but for tyre issues. They made up for that disappointment by winning the 1951 crown: Norton’s first and last. And please note, only the production bikes were given the Manx tag; not the factory bikes!