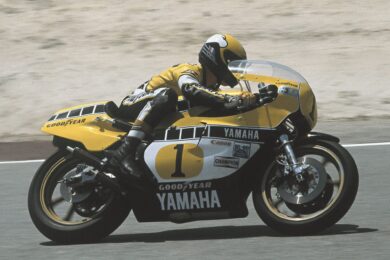

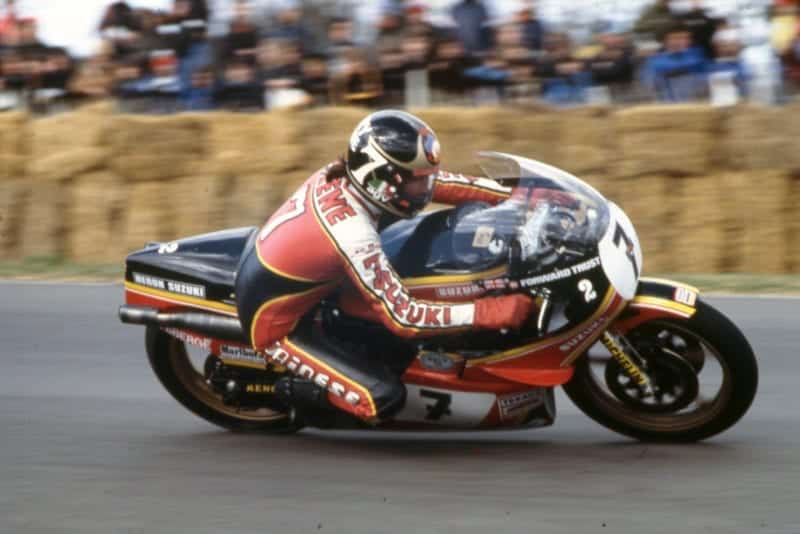

Sheene scored his first GP win in the 125 class at Spa in 1971 and he would’ve won the 1976 Belgian GP on his way to his first world title if his RG hadn’t gone sick. When he returned in July 1977 he was once again leading the world championship, fending off Steve Baker’s factory Yamaha. Victory at Spa would very nearly put the title out of Baker’s reach.

One of Sheene’s two new team-mates in 1977 was best mate Steve Parrish, who had never raced on a street circuit. Sheene showed the youngster what he was in for by taking him for a few high-speed reconnaissance laps in his Rolls-Royce, but nothing could prepare Parrish for the reality.

“I remember it vividly – the main thing was the daunting speed of the place,” says Parrish, who was riding a year-old ex-Sheene factory RG500. “I remember riding through that long right-hander through the village of Burneville, thinking, ‘Fuck me, if it goes wrong here… this is just lunacy’. That corner was like an enormous Gerrards [at Mallory] – well over 100mph [160kph], but with no run-off whatsoever. Then there was that nasty fourth-gear kink on the Masta straight. That was one of those hold-your-frigging-breath-and-get-through-it corners. I suppose the good thing was there wasn’t a lot of corners to remember because most of the lap was just pinned.”

“He asked us if we’d fixed the problem and we said ‘yeah’, so he said, ‘okay, let’s do it’, We had to know that if we lied to him we could kill him, simple as that.”

Baker, another street circuit virgin, also made his Spa debut that July. “I went around in my car before practice,” says the American. “My first thought was, ‘Oh God, what have I got myself into here?’. It was pretty scary. The thing was that however dangerous it was, you had to keep your corner speed up because with the 500 engine’s power characteristics that made a huge difference in lap time.”

Spa had only one slow corner – the final La Source hairpin, taken at 20mph [30kph]. Parrish remembers being so ‘speed drunk’ that it was very tricky to judge his speed into the corner. “Then you’d have an awful lot of clutch slipping out of there because of the ridiculously high gearing you were using.”

Sheene didn’t start the 1977 Spa GP from pole. He got stung by a hornet during qualifying and ended up second behind Suzuki privateer Philippe Coulon. In fact the hornet was the least of his problems.

These were days of spiralling two-stroke engine performance, which had the tyre companies and chassis makers struggling to keep up. Only two years earlier Sheene had come close to death at Daytona when he was flung down the road at 170mph [275kph] after his rear tyre popped.