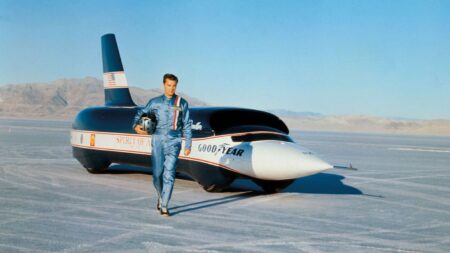

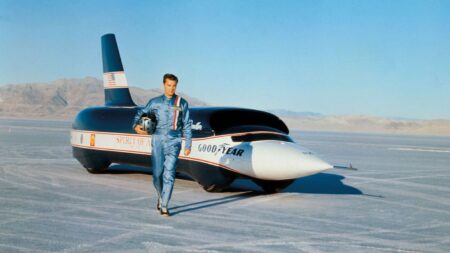

Spirit of America: Sonic I - World's first 600mph car sells for $1.3m

The world's first 600mph car, Spirit of America Sonic I, has been auctioned in a public sale for over $1m

Niki Lauda is of the opinion that a 1000bhp-plus Formula 1 car (on durable slicks, nice and wide and big and fat) would resonate with a disillusioned public.

He’s probably right – even though the sufficiently wealthy can today purchase road cars with substantially more grunt than that (and squirt them between mini roundabouts and sleeping policemen).

Imagine, then, the energising effect of that figure 89 years ago.

Especially as you consider the concurrent bold statement from its builders, The Sunbeam Motor Car Co. Ltd. of Wolverhampton, that this 1000-horsepower Land Speed Record challenger would achieve 200mph.

This at a time when the Air Speed Record was substantially south of 300mph.

When its driver Major Henry O’Neal de Hane Segrave first saw it running wide-open on the dyno – driving chains glowing red beneath armoured shrouds and its thunderous roar shaking the test house walls – he could conjure no reason to doubt either claim.

This American-born, raised-in-Ireland, Eton-educated Englishman did, however, briefly question his own ability.

“I stared at the monster rather as a child would have done,” he wrote in his 1928 autobiography The Lure of Speed. “The thought that I was to unleash all its potentialities was, one must admit, a little unnerving.

“It is the only time I can honestly say when I have stood in front of a car and doubted human ability to control it.”

No wonder.

Its stats were boggling: 23ft 6in long and 6ft wide, with chassis rails 24in deep, its 76cwt (3880kg) was to be propelled by a brace of Sunbeam Matabele aero engines that combined for 44.8 litres from 24 cylinders, 96 valves, 48 spark plugs, eight magnetos and four carburettors.

Faced by a dashboard bristling with 28 instruments – including six oil pressure gauges and four rev-counters – Segrave remarked wryly: “I won’t be bored.”

Though the most eye-catching stat was boastful – 870bhp was more realistic, with 748bhp officially recorded at the wheels – Segrave would nevertheless be squeezed between these masses of whirling metal as he plunged into the unknown.

Therefore the death of friend and rival JG Parry-Thomas during a LSR attempt on Pendine Sands in Wales was not only sad but also deeply unsettling.

Segrave received the news while relaxing by the swimming pool on RMS Berengaria. He had hoped that the six-day Atlantic crossing, with the 1000hp Car safely crated, craned and lashed to the Cunarder’s after-deck, would provide much-needed peace: “But this was not the case.”

It comes as no surprise to this writer that Segrave, the project’s liaison officer and sourcer of sponsorship as well as its driver, planned (in minutest detail) to keep his seat-time to a minimum.

Three runs along Florida’s reassuringly long (20-plus miles) but startlingly narrow (500yds) Daytona Beach were scheduled for March 1927: a shakedown, a sighter and the attempt itself.

Considering that the car had yet to turn a wheel in anger it proved remarkably resolved. It was, however, far from perfect.

Its drum brakes overheated; so, too, did its rear V12. Its gear-change was long and slow and did not fully engage in top, causing the selector to seize.

Most worryingly, it was easily unsettled by gusts and difficult to correct because of low-geared steering.

Segrave, too, was affected by aerodynamics. There being no front bulkhead, the howling gale almost blew him from the cockpit during his second run.

This was particularly concerning as he had been recorded at only 166mph.

In fact, he had gone faster – he calculated 180mph – but spectators had queered the clocks by driving across the timing strips and the American Automobile Association’s contest board thought it best to announce the most conservative of its figures.

This, however, caused the team to undertake an unnecessary reduction in sprocket size that robbed the car of 15mph.

Segrave returned the following week, on Tuesday March 29, after the remedial engineering work was completed. Now cocooned by a bulkhead and crouched behind a raised cowling, he performed with military efficiency andsang froid.

At least that’s how it appeared.

Once the rear engine, started by compressed air, had settled, he operated a hand clutch that slipped the other V12 into life via a coupling shaft.

He then engaged first gear and released the dog clutch that linked and synchronised the engines and trundled – the car was remarkably flexible – northwards to the start.

Having reached the far end of the nine-mile course, he U-turned and accelerated through the gears: 90mph in first, 135mph in second and an estimated 212mph at 2200rpm in top.

Once again the wind gathered him up, but an armful of corrective lock ended a 400-yard skid before the throttle could be lifted.

His problems continued beyond the timing strip.

Despite having fitted linings to the shoes, the brakes failed again.

Segrave’s hope that wind resistance would sufficiently slow the car proved misplaced – its all-enveloping bodywork, developed in Vicker’s wind tunnel, was efficient at reducing drag – and now he was faced with a dramatic choice: the Halifax River dead ahead, the dunes to his right or the ocean to his left.

Wisely he plunged for the latter. It did the trick and fortunately did not drown the engines.

There was no suggestion of aborting. Fresh 35x6in Dunlops were fitted as a precaution and the south-north return was begun well within the one-hour limit.

It was faster, too, due to a tail wind: “During the drive I couldn’t think of anything but what a mighty hard thing it was to make the car go straight.”

Photo: David Hunt

Minutes later Segrave, arms knotted with tension, was handed a restorative cigarette and the all-important slip of paper.

“You’ve done it, Major – two-oh-three!”

He considered a second run with the rear wheel covers, reckoned to be worth 5mph, fitted – they had been removed for fear of a puncture and flailing entanglement – but he was persuaded otherwise.

He’d beaten the previous record by 28mph.

His 203.792mph two-way average for the flying mile was sufficient. For now.

A future 1000bhp F1 car will, of course, far surpass that figure – without capturing the imagination in quite the same way.

But quite is sufficient. Right now. When the public thinks that F1 drivers are enjoying a stroll on the beach.

The sport holds within its power the ability to alter that perception. Does it have the will?

Calling 999 – and counting.

The world's first 600mph car, Spirit of America Sonic I, has been auctioned in a public sale for over $1m

Donald Campbell's water speed record craft, Bluebird K7, will go on display at Coniston after the end of a bitter legal battle. The man who led its restoration and recovery says it will be left a "dead machine"

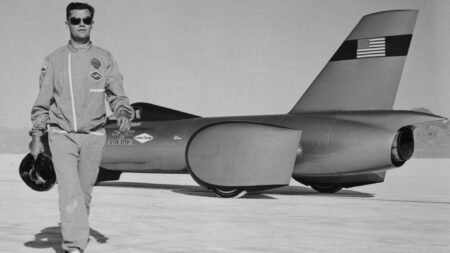

In a life dedicated to speed, Craig Breedlove was the first person to hold land speed records at 400mph, 500mph and 600mph, survived a 675mph crash, and never stopped dreaming about the next attempt

The irrepressible Ernest Eldridge was an unstoppable force in matters of velocity, becoming the last man to set a land speed record on an open road in 1924