Spirit of America: Sonic I - World's first 600mph car sells for $1.3m

The world's first 600mph car, Spirit of America Sonic I, has been auctioned in a public sale for over $1m

The day before heading to the Bristol-based launch of Bloodhound SSC’s cockpit the ‘phone rings in the office. “Hi Ed,” says PR man Jules Tipler, “we’re thinking of doing something a bit different tomorrow.”

“We want to try and show people what it’ll be like in Bloodhound’s cockpit for [driver] Andy [Green] and we thought you’d be a good person to try and simulate it on.” The last time I put myself forward for something out of the ordinary I ended up in a medical centre having had 180-degree water poured down my neck. For those of you wondering, the more recent 500-Mile Pedalo charity mission, on the other hand, was all my doing. However, if this was just a case of being spun upside down to simulate the 2g acceleration, as Tipler went on to describe, then what could possibly go wrong?

The launch of the Bloodhound’s cockpit the following day took place in that very British of motor sport destinations – a warehouse on an industrial estate – and it is astonishing how far the whole project has come along. It would be remiss of me to write about the Bloodhound SSC without quoting some facts and figures so here goes…

– The monocoque has taken 10,000 hours to design and manufacture. That would mean one person working eight hours a day – with no holidays – for five years.

– The monocoque was made using five different types of carbon fibre weave, two different resins and is, in some places, 13 layers thick.

– One of the (many) problems with trying to do 1000mph is that the Eurojet EJ200 jet engine can’t take air in that quickly. If it did it would choke the engine. So, in order to try and slow the air to less than 750mph, the roof of the cockpit has been shaped so that it creates a series of shockwaves to slow the air down.

– Thanks to the shockwaves – and the EJ200, rocket and V8 for fuelling the rocket – there’s likely to be 120 decibels of noise in the cockpit.

– The EJ200 fan sucks in 65 m3 of air every second so the latches on the hatch will have to withstand a quarter of a tonne of force. If they couldn’t the hatch would be ripped clean off.

20 tonnes – the drag of the car at 1000mph

50,000g – the force at the rim of the wheel at 10,200rpm

55 seconds – time from 0-1000mph

17 seconds – time from 500-1000mph

3.6 second – time taken to do the flying mile

180 decibels – the hybrid rocket could be louder than a 747 at take off

3000 degrees – the hybrid rocket temperature

On top of that the cockpit will have to endure aerodynamic loads of up to three tonnes per square metre. The ballistic armour the cockpit carries isn’t actually to help with that, though; it’s to protect Green should a stone get thrown up at 1000mph…

The list of baffling figures is endless and it’s a testament to the team behind the project that the car is on target from both design and time perspectives.

So… the simulation… When I arrive I am handed an iPad game where you tilt the tablet forward to start accelerating the Bloodhound, deploy the rocket, try and keep the car roughly in a straight line, drive through the measured mile, start to slow, deploy the air brakes and then, finally, the parachute.

Needless to say, the first time I try I miss the measured mile (it really is very difficult to keep the car in a straight line…). On the next two attempts I actually manage it all and on one occasion I clock over 1000mph. A small part of me thinks that I can replicate my success again in front of the crowd having been flipped upside down. It turned out to be misguided optimism.

Green explained what it’s like to drive a Land Speed Record car and – with the help of the on-board video of Thrust SSC, where he’s on opposite lock for an alarming amount of time – made it clear that it’s actually very difficult to drive in a straight line at speeds over 400mph.

My time came and I was strapped onto a frame, handed some ear plugs and given the iPad. In case I thought I could get away with just pretending to do a good job, the iPad’s screen was replicated on large TV screens in front of the 150-strong crowd. As I set off a 120-decibel simulated noise starts to play from speakers large enough to make Daft Punk jealous and, when I press the rocket button, Tipler flips the frame so that I am suddenly hanging upside down.

Anyone who has used an iPad will know that if you flip it upside down everything reverses. I now had to steer left to go right and tilt the screen back to carry on accelerating. All of that was pretty much a waste of time, though, as I was now so far off the painted line I was supposed to be following, I was gently heading out of South Africa – where the record attempt will take place – towards Botswana.

Photo: Craig Scarborough

A rather embarrassing minute then passed with me desperately pressing all the buttons I could think of before it was time to get flipped the right way up and for me to re-tuck my shirt back in to hide my embarrassingly exposed stomach.

“How was that?” Asks Green.

“Great,” I reply. In hindsight it was a stupid response. It was so far from ‘great’ that I’d be lucky to hold onto my driving licence if the DVLA saw the footage. While it wasn’t a true reflection of what the record attempt will be like for Green, it did partly simulate about a tenth of the number of things he is going to have to think about when travelling across the earth at 1000mph.

The car looks like it will be ready to start low-speed testing – at a mere 200mph – in August 2015 on Newquay runway and it will then be shipped to South Africa to start high-speed testing between then and October.

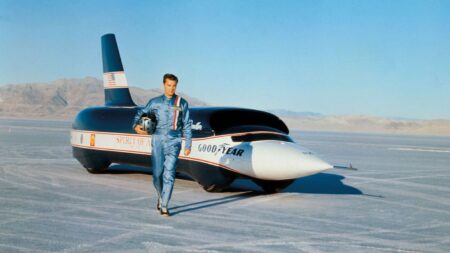

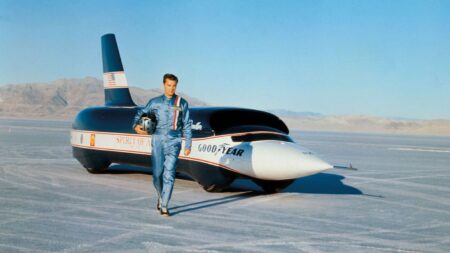

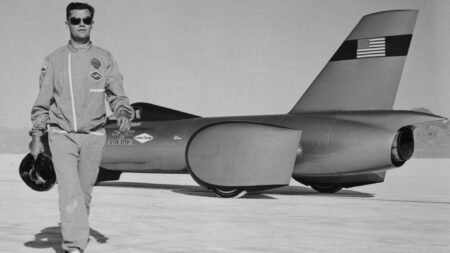

The world's first 600mph car, Spirit of America Sonic I, has been auctioned in a public sale for over $1m

Donald Campbell's water speed record craft, Bluebird K7, will go on display at Coniston after the end of a bitter legal battle. The man who led its restoration and recovery says it will be left a "dead machine"

In a life dedicated to speed, Craig Breedlove was the first person to hold land speed records at 400mph, 500mph and 600mph, survived a 675mph crash, and never stopped dreaming about the next attempt

The irrepressible Ernest Eldridge was an unstoppable force in matters of velocity, becoming the last man to set a land speed record on an open road in 1924