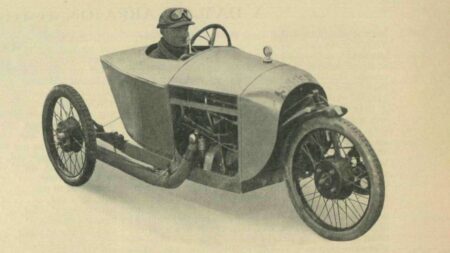

Born in July 1897 into Hampstead wealth and comfort, Eldridge had burst onto the speed scene in 1922 – the year in which he stepped from an aeroplane crash and also reportedly lost tens of thousands on the turn of a card – aboard a 1907 Isotta Fraschini, its chassis stretched to accommodate a six-cylinder 20.5-litre Maybach airship engine.

It was not fast enough for his liking.

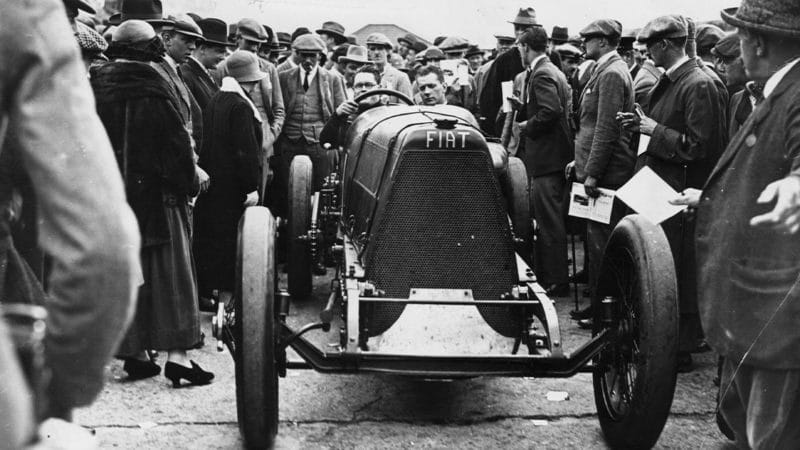

So he bought for £25 the remains of the 1908 Fiat that, according to previous owner Captain John Duff, was “inclined to roguery”; its engine had blown up monumentally, almost decapitating the aforementioned.

Despite a capricious nature and lack of formal training, Eldridge was a talented engineer: the prototype garagiste in his Vauxhall Bridge Road workshop.

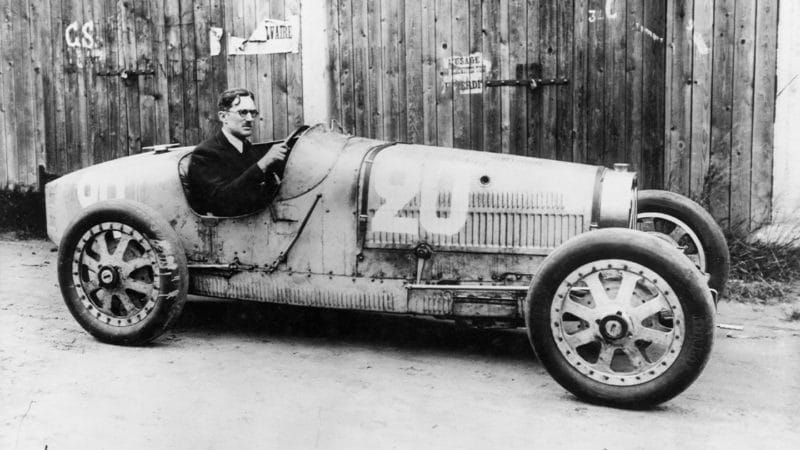

An extra 18 inches – using material reckoned supplied by the London General Omnibus Company – were spliced, this time to make space for a 21.7-litre Fiat A1.2 ‘six’ tweaked – four plugs per cylinder instead of two and compression raised by 0.5 to 5:1 – to give 350 horsepower at 1800rpm.

Substantial by any measure – 16ft 8in long and almost 4000lb – the flywheel alone weighed 175lb, while its clutch comprised more than 50 plates.

The beast was encouragingly quicker – though gallingly beaten at Brooklands in April by the Isotta-Maybach handed a 20sec handicap – and the fearless Eldridge drove it like he stole it.

Thus, to be denied by a technicality went against his grain.

He returned to the 4.5-mile straight on the Paris-Orléans road six days after his knock-back. How Mephistopheles had been adapted to comply in that time has never been satisfactorily explained.