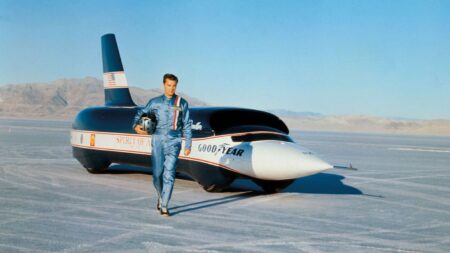

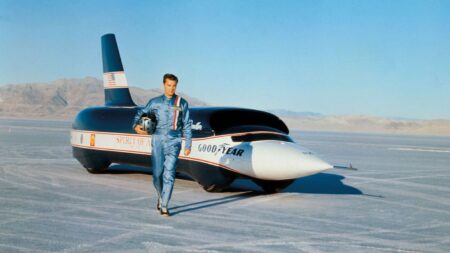

Spirit of America: Sonic I - World's first 600mph car sells for $1.3m

The world's first 600mph car, Spirit of America Sonic I, has been auctioned in a public sale for over $1m

I was five when Gary Gabelich broke the Land Speed Record in October 1970 and, I guess for that very reason, it was a very big deal. I don’t think you understand much about speed at that age and I certainly didn’t appreciate that Gabelich really didn’t raise the record by much at all, LSR-wise. Decimal places aside, he improved it from the 601mph where it was left by Craig Breedlove five years earlier, to 622mph. Breedlove by comparison was the first person through 400, 500 and 600mph and did it all between 1963-65.

But I was six weeks old when Breedlove set his last record and had my mind on other things. By the time Gabelich turned up at Bonneville I was a fully tuned in, pocket-sized petrol head. But of course the real reason it earned my undivided attention had nothing to do with the man at the wheel, it was the car to which that wheel was attached. The Blue Flame. Or, to give it its full name, the Reaction Dynamics Blue Flame. No Land Speed Record car ever sounded cooler. Not even George Eyston’s Thunderbolt. Nor did any ever look better. Even now, 46 years after Gabelich streaked across the salt, I look at the Blue Flame and find it aesthetically unimprovable.

Photo – Tom Margie Flickr

If someone wheeled it out today as a brand new Land Speed Record car we’d still all coo over a shape that made it look like a rocket on wheels. That, in very precise terms, is exactly what it was. But I love the details too, from the angle of the stabiliser fin at the back and design of the cockpit area to the way it changes colour along its length. Visually it is, was and will always remain the perfect visual expression of the Land Speed Record breaking art.

That is odd because the Blue Flame is actually the exception to the Land Speed Record-breaking rule. For the last 110 years every record has been set by a car powered either by an internal combustion engine, or a jet. All, that is save the Blue Flame, which was powered by the aforementioned rocket.

I had always wondered why more LSR cars had not been rocket powered. There have been others, notably the Budweiser Rocket in which Stan Barrett claimed to have gone supersonic in 1979, but the record was never proven nor ratified. But rockets are light, very simple, generate huge power and don’t require the huge air inlets needed by jets that define their shape and frontal area. Perfect LSR propulsion units, you might therefore think. It took none other than Richard Noble to explain to me that while rockets are very good at gaining speed, they’re not that great at maintaining it for the period of time required to set a Land Speed Record at a speed that is the average of two runs in opposite directions within a one hour timeframe. That made me admire the Blue Flame boys even more. Whatever speed it actually reached and whether it broke the sound barrier or not, no one disputes the fact the Budweiser Rocket only ever ran in one direction.

Photo – Flock and Siemens

But next year if all goes according to plan, a rocket powered car will break the Land Speed Record for the first time in 47 years. The Bloodhound SSC isn’t the best looking LSR car, nor does it have the best name, even if it is named after a 1950s surface to air missile designed by Ron Ayers who is also the new car’s chief aerodynamicist. But in its use of all three principal power units – rocket, jet and internal combustion engine – it is unique. Essentially the jet gets the car going so rocket fuel isn’t wasted at speeds for which it is not needed, only kicking in above 300mph to push the car through the sound barrier and beyond. A 5-litre, 550bhp supercharged Jaguar engine acts as a fuel pump for the rocket.

I went to see Bloodhound this week. It’s around 80 per cent complete and should be ready to run in South Africa next year. Although its creators may beg to differ, it is not a beautiful car. But it is brutally purposeful and full of details to delight the LSR-obsessed child that still lurks within me. It has a normal speedometer for instance, normal save the fact that it reads up to 1100mph and that its secondary calibrations are not in kilometres per hour, but Mach. Its steering wheel and the very tip of its nose are both 3D printed – in titanium. And there’s even a conventional rev-counter and stop watch in there, both purpose built for Bloodhound by Rolex.

Photo – Flock and Siemens

So once more I’m getting excited by the Land Speed Record and the prospect that, 20 years after he became the first and to date only man to have indisputably travelled across the surface of the planet faster than sound, Andy Green might break his own record in 2017. But that will only be the start: if all goes well next year, the car will spend that winter being equipped with the more powerful rockets required to push it past 1000mph in 2018.

And there I expect the history of the Land Speed Record will come to an end, at least for those reading this today. The sad truth is that in the last half century the Land Speed Record has only been broken three times and the speed raised by less than Breedlove managed in just two years. It has reached a level now where going faster has become an exponentially more difficult process. If Bloodhound does manage to raise it from the 760mph at which it has stood these last 19 years to over 1000mph it will be the greatest achievement in Land Speed Record history and, in my lifetime at least, the last. And that will make me happy, proud and just a little bit sad.

The world's first 600mph car, Spirit of America Sonic I, has been auctioned in a public sale for over $1m

Donald Campbell's water speed record craft, Bluebird K7, will go on display at Coniston after the end of a bitter legal battle. The man who led its restoration and recovery says it will be left a "dead machine"

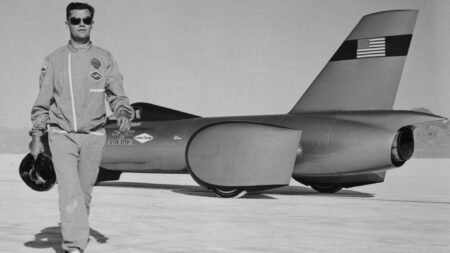

In a life dedicated to speed, Craig Breedlove was the first person to hold land speed records at 400mph, 500mph and 600mph, survived a 675mph crash, and never stopped dreaming about the next attempt

The irrepressible Ernest Eldridge was an unstoppable force in matters of velocity, becoming the last man to set a land speed record on an open road in 1924