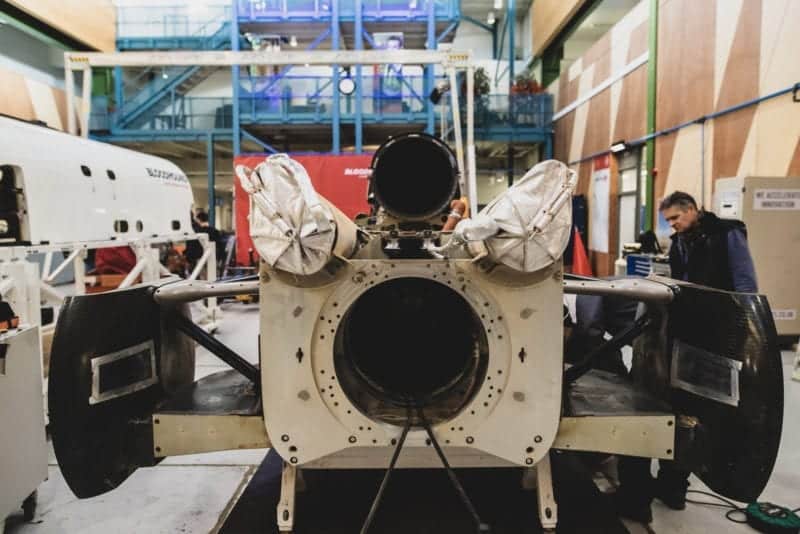

The parachute housing at the rear also shows the strain the car has been put under, the left chute bending the teardrop edge out of shape through sheer force during deployment.

A rough steel strip has been secured into place ahead of the rear left wheel, rivet heads sticking out from an otherwise smooth surface. Protective in function, unfussy in form.

Today, the beating heart of Bloodhound is being removed and returned to Rolls-Royce where it will be cleaned, serviced and stored.

The EJ200 jet has been specifically chosen for the project, its power-to-weight ratio making it ideal for a land speed record attempt.

Bloodhound has been built around this unit; its bodyshell providing a clearance of just millimetres between it and the jet engine. Andy Green’s cockpit is shaped to create shockwaves as the car races along, to compress and slow the air so much so, that if 1000mph is achieved, the air going into the jet engine would only be around 600mph, such is the precision and ingenuity of the design.

Just three pins, no more than an inch in width, a few inches more in length, hold the engine in place, supporting the engine from either side with one supporting in the centre.

Now clear of the bodywork, the engine is prepped for part two of the job

Will Broadhead

That central strut, a fifth of the way along the engine, is subjected to the entire thrust load of the LSR car going through it.

It means that while the car is skimming the desert, approaching the sound barrier, the engine itself is actually moving about within the car.

Run data reveals the wobbling, showing the engine moving back and forth during a run by up to 20mm. But the effect on stability is minimal compared with the aerodynamic buffeting.

Why more funding is needed quickly becomes evident as I’m shown the trolley that we’ll be lowering the engine into: a bespoke contraption that costs £50,000.

While the experts delicately attach the chain hoist to the engine, I’m left with unscrewing bolts and preparing the trolley – which is easily enough responsibility for me, considering it’s ten times more valuable than the car that I drove over in.

The engine’s raised, a stray filter removed and the Eurojet EJ200 unit slots onto the metal frames of the trolley.

We wheel it out from under the ribcage — the skeletal shell of the car. The trolley journey isn’t long — eight metres to be precise — which works out a cost of £6250 per metre, excluding labour.

The engine is slowly lowered into the frame ready to be sent back to Rolls Royce

Will Broadhead

The engine’s now free of its white shroud, revealing miles of zip-tied wiring, a maze of tubing, and evident wear on the inner shell – evidence of its efforts in testing.

A significant number of bolts, wires and tubes remain from the engine’s days as an Air Force test unit, attached to orange panels.

“Anything attached to the orange stuff is useless and isn’t connected,” former Army tank engineer John explains to me. I still keep well away.

The final — and trickiest — phase is to hoist the engine once more and place it into the ‘egg’, a tight metal frame shell that will protect it during its return to Rolls-Royce. The name is “a Royal Air Force thing”, I’m told.

I’m regretting my enthusiasm, as I’m given the job of supporting the front of the engine during the delicate operation.

I take up position in front, and up close, trying to hold it steady, and in position as the hoist lowers it agonisingly slowly, with every minor twitch and sway being exaggerated at the opposite end.

Jake steadies the engine

Will Broadhead

I’m expecting a clang of metal, a crack of turbine blade or a ripping of wires, but the engine comes slowly to rest, we bolt it to the frame and pull over the protective bag, to make it ready for pick-up.

Looking back over the workshop floor to Bloodhound’s empty shell is a reminder of what might have been in December 2018. The project was in administration, and angle grinders were ready to break up the car, which had been a decade in development, so its military components could be returned to the Ministry of Defence.

An eleventh-hour rescue by businessman Ian Warhurst rescued the car and has brought the project to this stage, but he’s clear that further funds are needed from sponsors if it is to return to South Africa.

After the success of testing, there’s an air of quiet optimism about the project.

“Ian’s been very clear that his money funded high-speed testing and he’s – and we all are – pushing really hard to get that funding in place, but we won’t commit to a date in South Africa until that money exists,” engineering director Mark Chapman explains.

“It [sponsorship] should happen. It comes down to timings. Again, by putting it into next year, it makes it a lot easier because it comes under 2021 budgets and a different financial year.”

Data from the sensors suggest that very little work is needed for the car to achieve the main goal.

“There’s nothing we saw in South Africa that gave us some concerns for going up through the sound barrier. It is as trivial as putting a rocket in the back.”

So, nestled snugly in its egg for now, the next time that the world sees this particular EJ200 could be when it’s travelling beyond the speed of sound, in a car going faster than any other before it.