Denis Jenkinson's Porsche 356 roars again at Goodwood

Six decades after Motor Sport's famous continental correspondent Denis Jenkinson ran his Porsche 356 across Europe, it's now racing again following a long and careful restoration

Nürburgring Nordschleife and its (4.8-mile) Sudschleife offshoot never made ‘sense’.

Built in the euphoric aftermath of the Weimar Republic’s hyperinflation of the early 1920s to create employment and generate income in a German backwater, its scope was epic: a never-to-be-repeated lap of the gods.

I have no doubt that should you mull a list of 20 or so fantastic drives that it will include several Lords of the ’Ring: Caracciola, Nuvolari, Rosemeyer, Ascari, Fangio, Brooks, Moss, Clark, Hill, Surtees, Stewart and Ickx. For so extensive yet intensive was the examination set by this circuit that not only did it distil the great from the good, it also refined the absolute best. Though often foggy, the ‘Green Hell’ was never a happy hunting ground for sufferers of red mist.

Niki Lauda’s fiery accident of 1976 was Formula 1’s Last Rites at the track, but the World Sportscar Championship and Formula 2 clung on through flips – Manfred Winkelhock’s March 802 and Stefan Bellof’s Porsche 956 – and spins to the bitter end.

Except that it wasn’t the end.

‘Sense’ prevailed in 1984 when the new Nürburgring was opened. Castigated at its anodyne outset, the years have been kind to it: it’s not a bad track and has hosted some good races. Yet it has never emerged from the shadow of its big brother up in the mountains. Nordschleife is a place of pilgrimage. Pay your Euros and you can retrace the Lords’ wheel tracks. But might this privilege be revoked any time soon?

Like all major European tracks, Nürburgring is dealing with the fact that Middle East oil money now greases F1’s cogs. Both it and Hockenheim have had recent disputes with Bernie Ecclestone and since 2008 have shared the spoils of Germany’s GP on an alternating basis.

Nürburging bosses were fortunate, therefore, to have a USP: Nordschleife. For some reason, however, they deemed this insufficient. Ignoring its core, they went for ‘Cor!’ and built a theme park complete with roller coaster and, I kid you not, a Fangio-themed steakhouse called El Chueco.

‘Nüro Disney’ never made sense, never mind ‘sense’, and now lies all but empty while pistonheads continue to crank it up on motorsport’s biggest ‘roller coaster’ before cramming into the Pistenklaus down the road for a celebratory bier or drei.

Huge outlay plus small income equals big debt and a vexed local government. More bartering with Mr Ecclestone surely lies ahead and it’s clear who holds the stronger position there, while Hockenheim’s better access and surrounding infrastructure – plus it’s Sebastian Vettel’s local track – make it the GP’s more obvious home for the foreseeable future.

It’s hard to imagine titanic Nordschleife being dragged under by this, but those closer to the subject than me have felt sufficiently nervous to create petitions and go public. Should the gates be locked and the track fall into disrepair, we could easily have another ‘Brooklands’ on our hands.

I have been lucky to tackle Nordschleife – reverentially, i.e. slowly – in historically important machinery and so won’t be nipping through the Chunnel to fang around it in a hot hatch while I still can. But talk of its potential demise has caused me to revisit another precious memory.

The underfunded Fearnley family never got beyond Thruxton during Nordschleife’s heyday, but its youngest member, as a junior reporter for Motoring News in 1993, did attend the last full-shot sprint race held there.

That inaugural season of hi-tech Class 1 DTM saloons included back-to-back four-lappers of Nordschleife-plus-GP-Strecke: 15.7 miles. With Nicola Larini cast in the role of Nuvolari, Alfa Romeo upstaged Mercedes-Benz, as it had in 1935.

© Alfa Romeo Automobilismo Storico, Centro Documentazione (Arese, Milano)

During practice I ventured to the left-over-crest of Pflanzgarten. Uwe Alzen, a bullish racer never short of commitment, was first through. His Merc 190E – in name only – landed askew and I took a pace back from the shallow Armco that separated me from him. Nordschleife is like that: it grabs you immediately, and doesn’t let go thereafter.

Larini, despite 33kg of success ballast accrued by four prior wins elsewhere, led both races from start to finish in his total-traction V6. Hardly classic encounters in themselves, it was the venue’s grandeur and historical context that made them stick in the mind.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C-edLvr4Mv8[/youtube]

Larini tended to gain time on the modern portion of the track before managing the gap over the old majority. Cameras in his cockpit reminded you how bumpy Nordschleife is, and caught him smiling as he glanced left at the Karrussel’s exit to scope his pursuers.

There was a camera in his footwell too. On the descent from Hohe Acht, the circuit’s highest point, his left foot hovered mindfully over the brake while his right mashed the throttle. He tapped the middle pedal on occasion but barely with sufficient force to connect pad with disc. He was brave. His appreciative crew mobbed him. And I was there.

That, at least, is ring-fenced.

Six decades after Motor Sport's famous continental correspondent Denis Jenkinson ran his Porsche 356 across Europe, it's now racing again following a long and careful restoration

Voice of 90’s motor racing is completing project to revive hidden gems of motor sport film and television.

Ferrari's F1 car is set to feature a 'blue livery' at the 2024 Miami GP – we look back on the other times Maranello cars haven't run in red

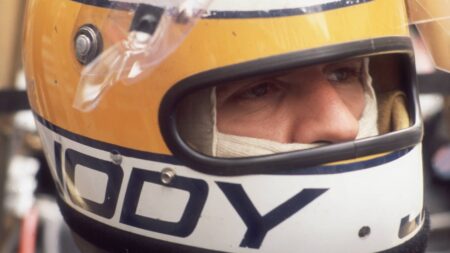

Think of the great Formula 1 champions and Jody Scheckter is unlikely to feature. But, writes Matt Bishop, the 1979 title-winner deserves more acclaim for a career in which he was once the best driver, bar none