Coatalen’s hand had been forced by the late arrival of Fiat’s six-cylinder Tipo 804; small and neat – from rounded radiator cowl to wedge tail via steeply staggered seats, full-length undertray and enclosed tail pipe – as well as low and light, it set new standards for packaging – and promptly practised some 30sec faster than Sunbeam’s best. Only one of the three entered finished – weak back axles causing two late accidents, one of them fatal – but it won.

So Coatalen reached for the company chequebook again – and this time doubled down: Vincenzo Bertarione and Walter Becchia, members of the talented team that had worked on the Fiat under the direction of Guido Fornaca, were spirited from Turin and, as such, the 1923 GP Sunbeam basically would be a six-cylinder ‘green Fiat’ – albeit with detailed changes/improvements: slower piston speeds due to a reduction of the bore/stroke ratio; larger valves (just two per cylinder) at a narrower angle; and cams driven by gears at the rear of the engine rather than by Fiat’s Y-arrangement of shafts and bevels.

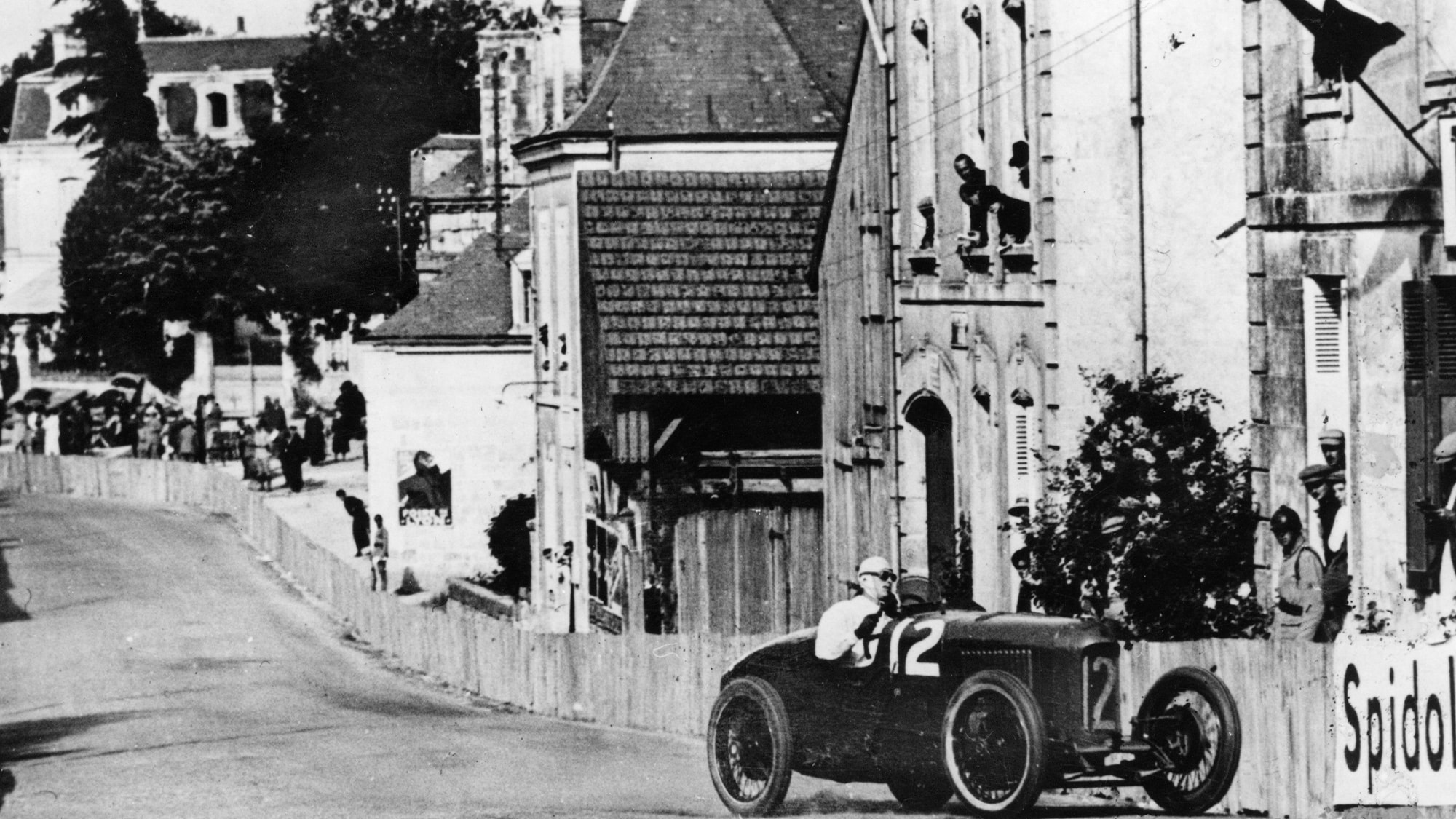

Britain’s best had never been so well placed: its cars, the lightest in the race, this time to be held in Tours, had been thoroughly tested beforehand and tailored to suit their crews, while the support team, honed by bitter experience, was well equipped and practiced.

One of the Sunbeams would be pressurising the Fiats throughout the 35 laps

Works driver Henry Segrave, by inclination a purveyor of fastest laps, vowed to make the most of the opportunity this afforded him in the season’s most important race. His previous attempts had resulted in 14 tiresome punctures (and last place) and three weeks in bandages because of burned backside caused by spilt petrol (before the merciful release of retirement.) Accordingly, this time he resolved to hold back in the early stages to save his machinery. Not that he could match the Fiats in any case.

The Italians had again arrived late and with by far the fastest car: a straight-eight this time, boosted by a supercharger – a GP first – driven from the nose of the crankshaft. The Sunbeams had been training assiduously for three days by the time Pietro Bordino finally ventured onto the triangular, often narrow and heavily cambered, 14-mile road course: his fastest was more than a half-minute under Segrave’s.

Sunbeam’s American-born Old Etonian raised in Ireland stuck to his (somewhat spiked) guns, however – he had learned that more often the race was not to the swift – while Bordino disappeared into a dusty distance from the two-by-two rolling start. Segrave had informed Coatalen of his cautious plan for this demanding 500-miler and received neither approval nor contrary instruction. But be it by good luck or by good management, the green team struck upon and operated an effective strategy: one of its number would be pressurising the Fiats throughout the 35 laps.

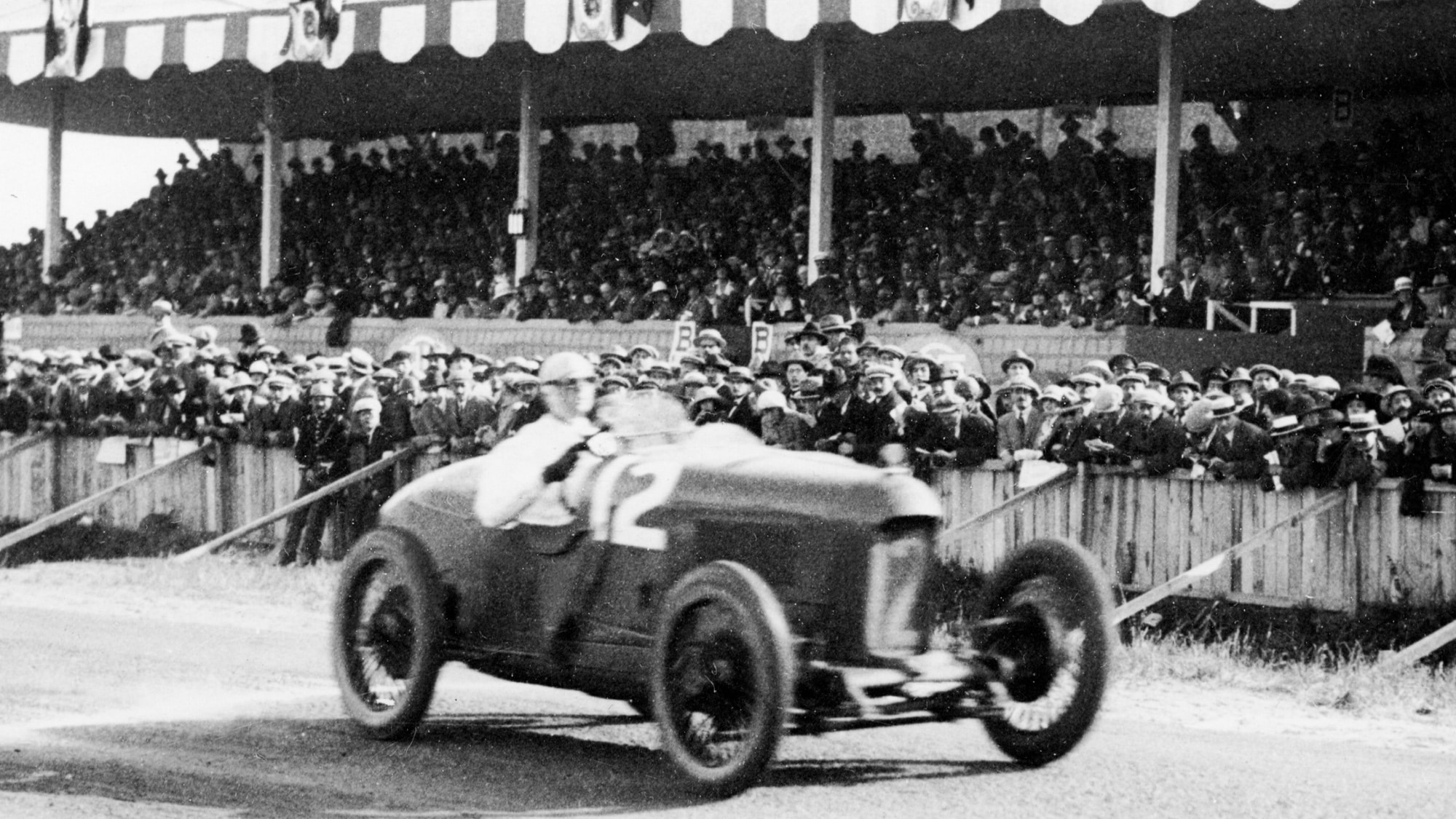

Kenelm Lee Guinness ahead of Albert Guyot (No3 Rolland-Pilain) and Ernest Friderich (No6 Bugatti Type 32 Tank) at Tours in 1923

Keystone/ Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Initially this role was fulfilled by Kenelm Lee Guinness, who inherited the lead – the first British driver to do so in a British car – on the eighth lap when Bordino’s engine failed; some say that a stone holed the Fiat’s sump and others that its low-mounted, unfiltered ‘blower’ had sucked up road dirt.