OK, so managing energy might not necessarily be a bad thing. But what about the heavy amount of contact in Formula E? Pound for pound, this grid is packed with arguably the best talent this side of F1. Only IndyCar can boast such a field of excellence. And yet every one of them in Formula E can end up looking amateur and ham-fisted by the tightness of the circuits and the physical nature of the racing those city tracks inspire. Imagine this grid on proper circuits in big, lairy, traditional single-seaters. Oh, hang on – I think I’ve just described A1 GP, the short-lived but fun ‘World Cup of Motor Sport’…

Doesn’t it get frustrating, Alexander? “It does…” he says, then pauses. “I would say by the nature of how robust the cars are and the fact you have got walls and not white lines, those track limits mean there is zero room for error, while the cars almost give you all the opportunity to create a contact-style situation. You know if you lose a bit of bodywork here and there it’s not going to damage your overall race pace. If there’s a bit of a gap you want to try and muscle your way through, but if you do that the walls are very close if it goes wrong. Everyone is operating at such a high level and it’s rarely an easy overtake.

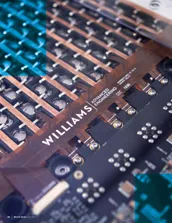

Sims won in Diriyah, 2019, with BMW

Formula E

“It is frustrating but it’s the way the series has been designed. They want exciting racing and to have that you need overtaking – and if you have lots of overtakes on a street track you get crashes.”

Sims’s point that the drivers are operating at a high level is absolutely valid. Both a strength and weakness of Formula E, it is so damned complicated, not only to watch, but also to compete in. Speak to any of the drivers and they give you a sense of how intense this form of motor sport is, all the time. There’s nothing else like it.

“Formula E is mentally very challenging and that brings its own set of emotions”

“I think that’s absolutely fair,” says Alexander. “I’ve driven in most different race cars around the world, whether it be in testing or racing and Formula E is by far the most demanding for the driver, in the car during the race. You’ve just got so many things changing all the time. Not only have you got to understand your energy consumption through the lap, you’ve still got to be driving fast through the corners and braking as late as possible. All those conventional things you do as a racing driver. But you’ve got regen levels changing through the first part of the race, tyres and brakes that are stone cold at the start because you don’t have a warm-up lap, then the brakes get really hot and as the regen feeds in you lose mechanical braking – so then your front brakes get cold and your brake pedal feels different… It’s just a constantly evolving target and it’s really challenging.”

No wonder then, that Sims counts himself lucky to have a dual racing life in GT endurance. He’ll be at Le Mans next month with Corvette and last year was part of Rowe Racing’s winning crew at the Nürburgring 24 Hours, sharing a BMW M6 GT3. A super-intelligent guy with a social and environmental conscience he might be, but Sims is a pure racer too. The fact is, like all his Formula E rivals, he loves it all.

Sims was part of the winning Rowe Racing team at last year’s Nürburgring 24 Hours

BMW

“Formula E is really enjoyable, but I’ve always said this: it’s enjoyable for different reasons compared to endurance racing,” he says. “It’s mentally very challenging and that brings its own set of emotions that you go through over a race day. But from a pure, conventional motor sport side of things the enjoyment of just hammering a race car lap after lap just isn’t there in Formula E because of the nature of the series, for all of the reasons we’ve discussed. I’m extremely fortunate to have a Corvette programme and to have done the Nürburgring 24 Hours with BMW to balance with Formula E. It’s lovely to do some GT races because there’s something about endurance, driving through the night, getting to Sunday morning and finding by lunchtime you’re knackered. As and when you do get a good result, my God, it’s a phenomenal feeling. It’s really nice to balance the two.”

That’s the heart of it. Formula E is complex, difficult and at times hard to love. But it’s still just motor racing. As it heads to London, us doubters really should give it another chance.