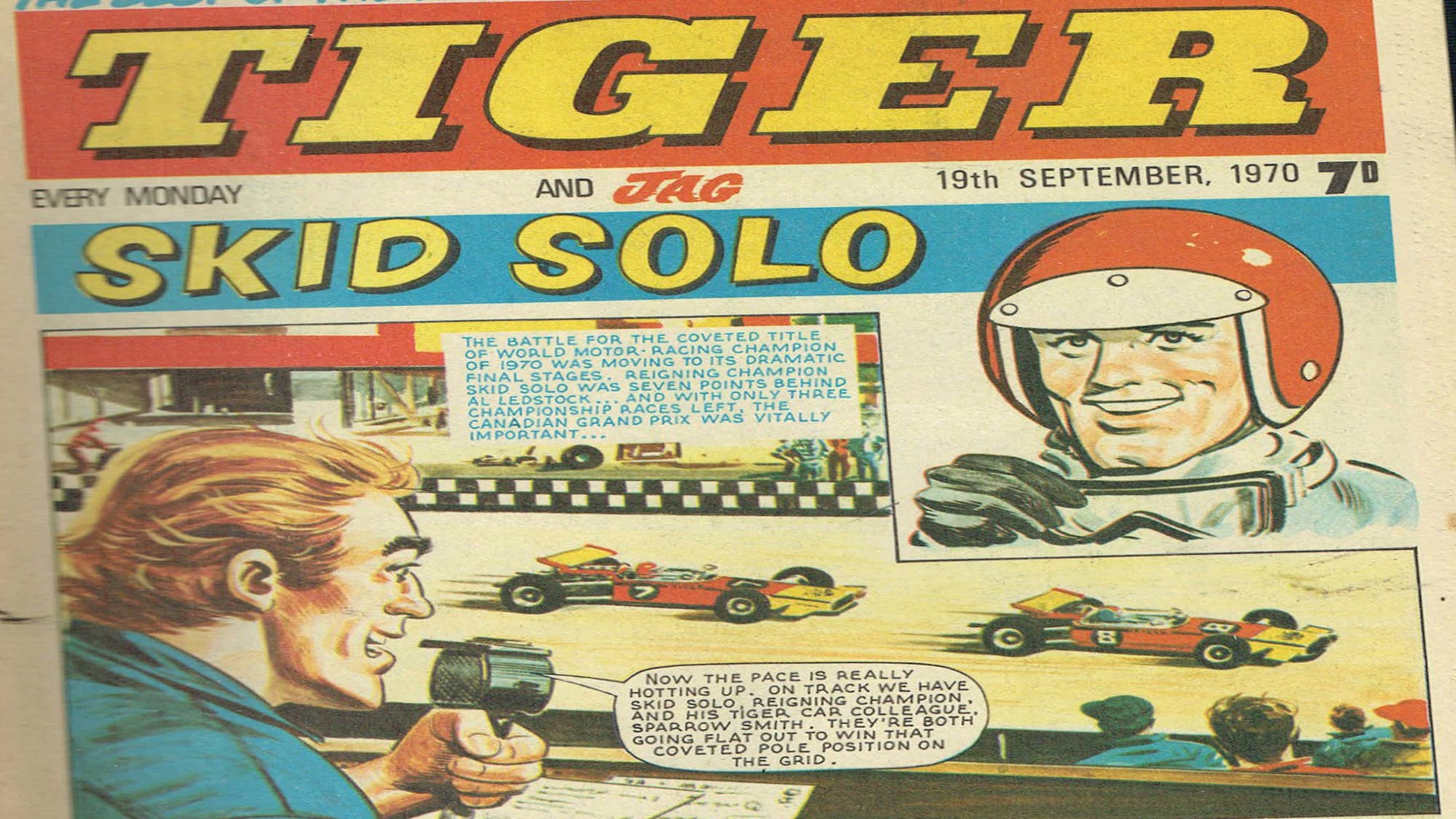

Skid Solo: The world's greatest racing driver — on paper

Skid Solo won his first F1 title going backwards across the finish line, and later teamed up with Stirling Moss in the BTCC. Paul Fearnley profiles the Tiger comic hero

Tilleys Vintage Magazines

Dad – a Vintage Sports-Car Club regular in our everyday chain-drive Frazer Nash – was my first motorsporting hero.

My second was a square-jawed multiple Formula 1 world champion called Skid Solo.

The Monday arrival of Tiger comic was the highlight of my pre-teen weeks. Three-and-a-half new pence well spent. Thanks, Nan.

I followed its numerous make-believe football stars – Roy Race (of Rovers fame), Nipper Lawrence, Billy Dane (owner of some mysterious old boots) and ‘Hot Shot’ Hamish Balfour – but only did so after devouring Solo’s latest escapade; followed by those of Martin (of Marvellous Mini fame) and Johnny Cougar, a wrestler from the alligator swamps of Florida.

Solo was well established by the time his innate ability on two – scrambling, speedway, etc – and four wheels – from Formula 1 to bangers – piqued my interest.

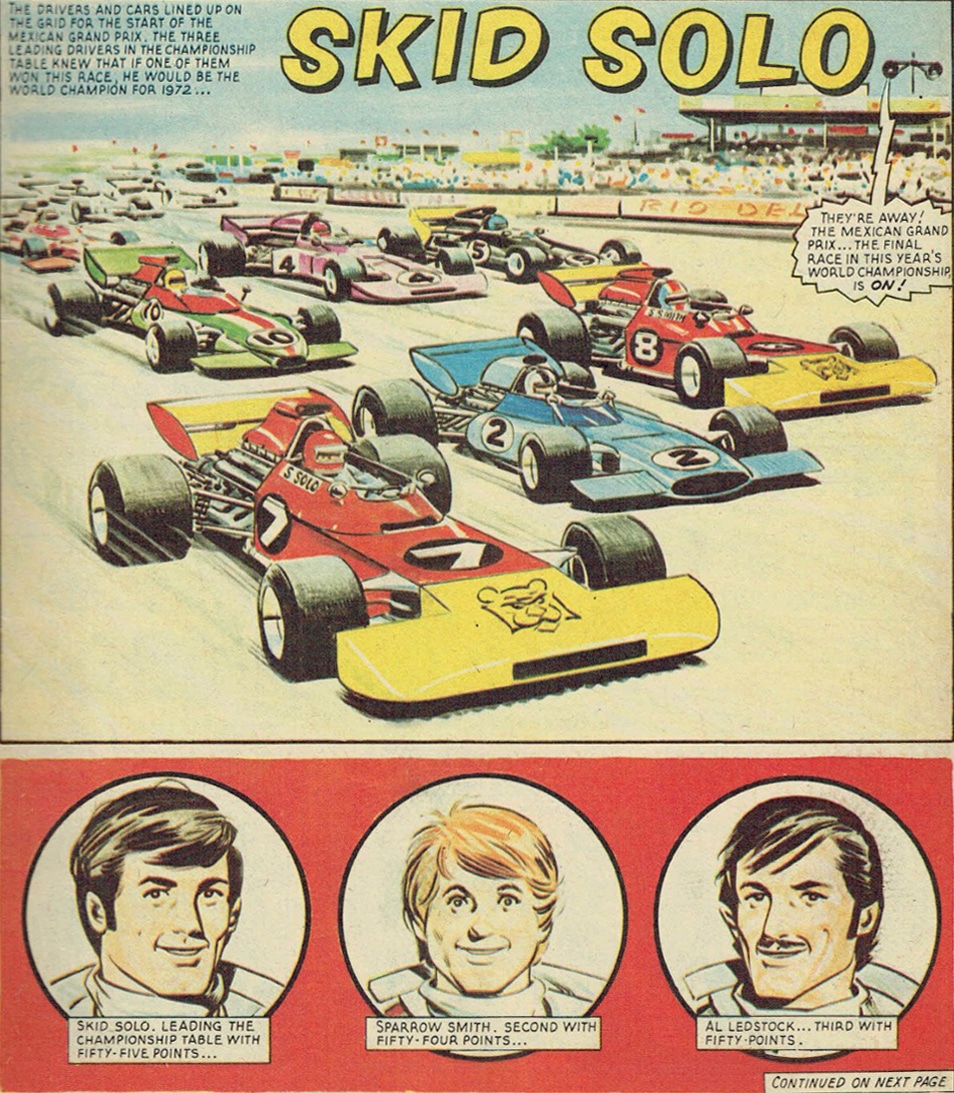

The 1972 nail-biter to decide the championship

Tilleys Vintage Magazines

He had first appeared in Hurricane comic in 1964, mowing Auntie Mabel’s lawn while daydreaming about going motor racing.

Auntie wanted Edward – a very rare reference to Skid’s real name – to work in a bank; a £1200 inheritance from his father was, however, burning a hole in an impulsive young man’s pocket.

What would turn out looking suspiciously like a Lotus Elan arrived in crates in the second instalment and Solo was building its rear suspension when dour (but likely secretly impressed) Mr Clothyard arrived to appraise his potential new clerk.

He first became world champion in 1966 – crossing the finishing line backwards because of a blown engine

Solo won on his DIY car’s debut – taking the lead on the last lap – and the rest would be made-up history. Surviving the subsuming of Hurricane by Tiger in 1965, his career would span a further 17 years.

He first became world champion in 1966 – crossing the finishing line backwards because of a blown engine – and had won the title (at least) twice more by the time I became a fan.

By then his F1 cars were red and yellow – on the occasions that his strip wasn’t black-and-white – and they were sponsored by Tiger itself; his chief designer/team manager was a no-nonsense bespectacled Scot called Sandy McGrath, and his younger team-mate was Sparrow Smith, a mechanic made good.

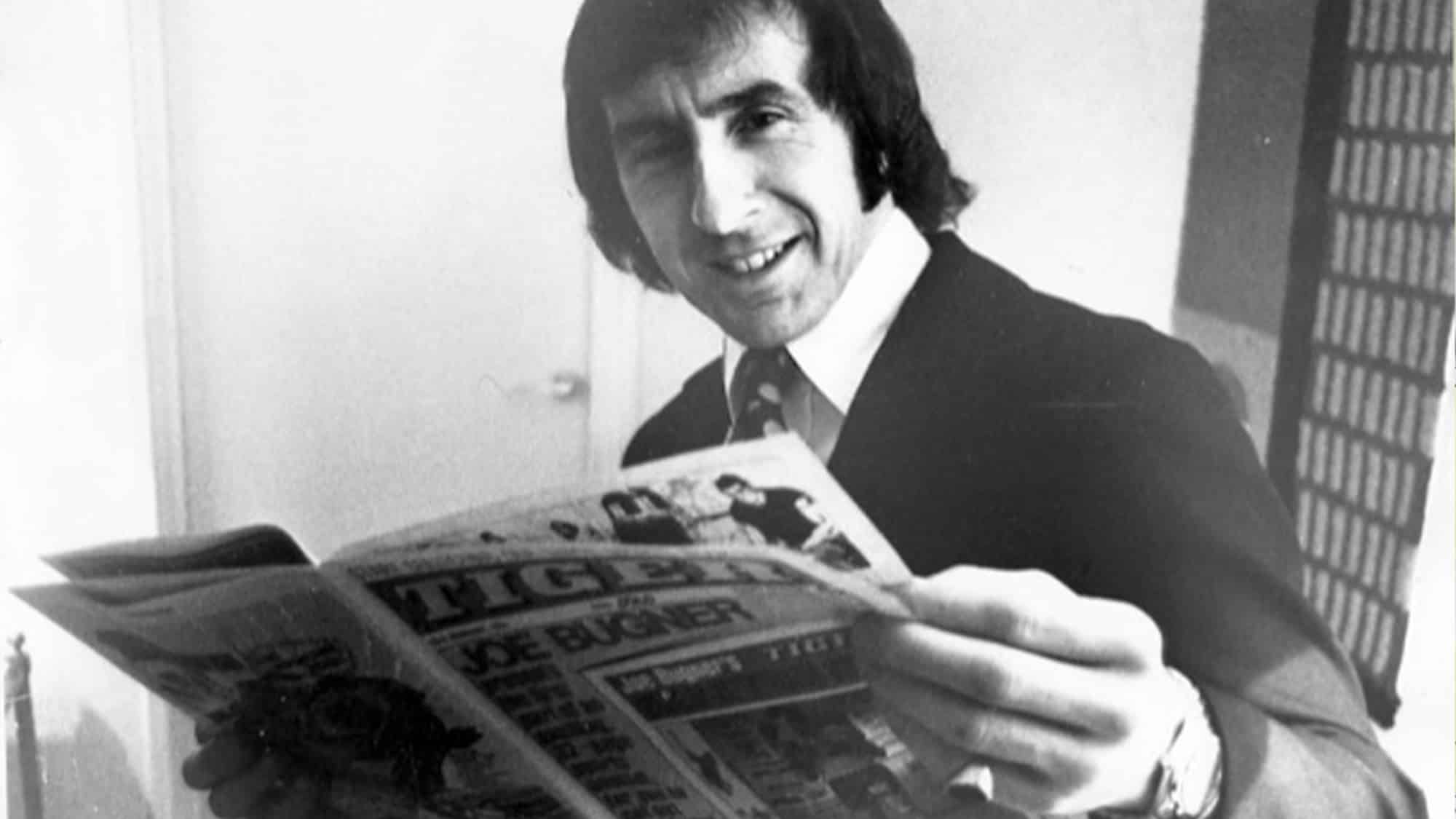

Jackie Stewart won the Tiger Sports Star of the Year Trophy in 1972 and 1974

Barrie Tomlinson

Fred Baker scripted the enjoyable plot lines – prolific, he also wrote Martin’s Marvellous Mini, Billy’s Boots and Hot Shot Hamish – but it was the drawings of John Vernon that hooked me. Solo’s innumerable cars always looked the part, aping the design trends of the real F1 – from Lotus ‘wedge’ to McLaren ‘Coke bottle’ to Brabham ‘pyramid’ – while retaining a signature squat shape with a chunky line.

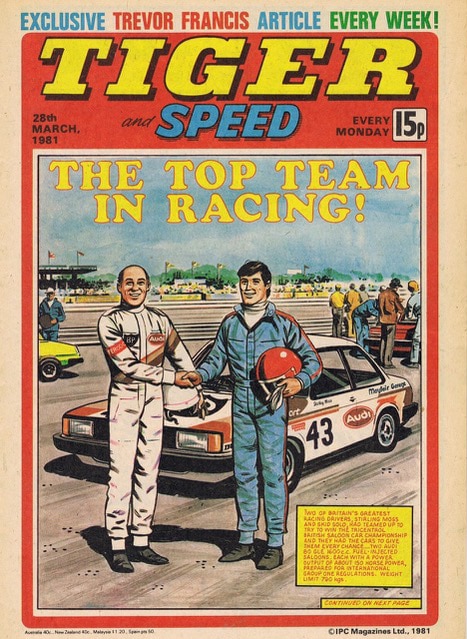

In a nod to Stirling Moss, they carried number seven. (Skid and Stirl would later team up in BTCC Audis.)

The editor of Tiger during this period was Barrie Tomlinson: “During my National Service in the Royal Army Pay Corps I did a bit of journalism because I was bored. That gave me the inspiration. Working on comics was my first full-time job and I learned as I went along.”

He joined boy’s adventure weekly Lion in 1961. Four years later he transferred to Tiger as Sub-editor. And by 1969 he was in its big chair.

Solo would be badly hurt in a testing accident caused by an errant dog

“Tiger was a sports-and-adventure title, but I decided to convert it to all-sports, and that proved very successful,” he says.

“All our contributors were freelance and I would have regular meetings with the scriptwriter to decide plots for the next couple of months. Fred was very good. His stories contained true-to-life ingredients but he’d always add that little sparkle that made them popular.

“But only very rarely would I meet the artist. John was a gentleman, softly spoken, very talented. I don’t know if he was a motor racing fan, but he must have been because of the way he drew it.

“Theirs was a strong combination – yet they hardly met.

“We had to have material to the printers six weeks before publication. I still don’t know why. I inherited that and never thought to change it. That made life a bit difficult. It would have been nice to have been more up-to-date sometimes.”

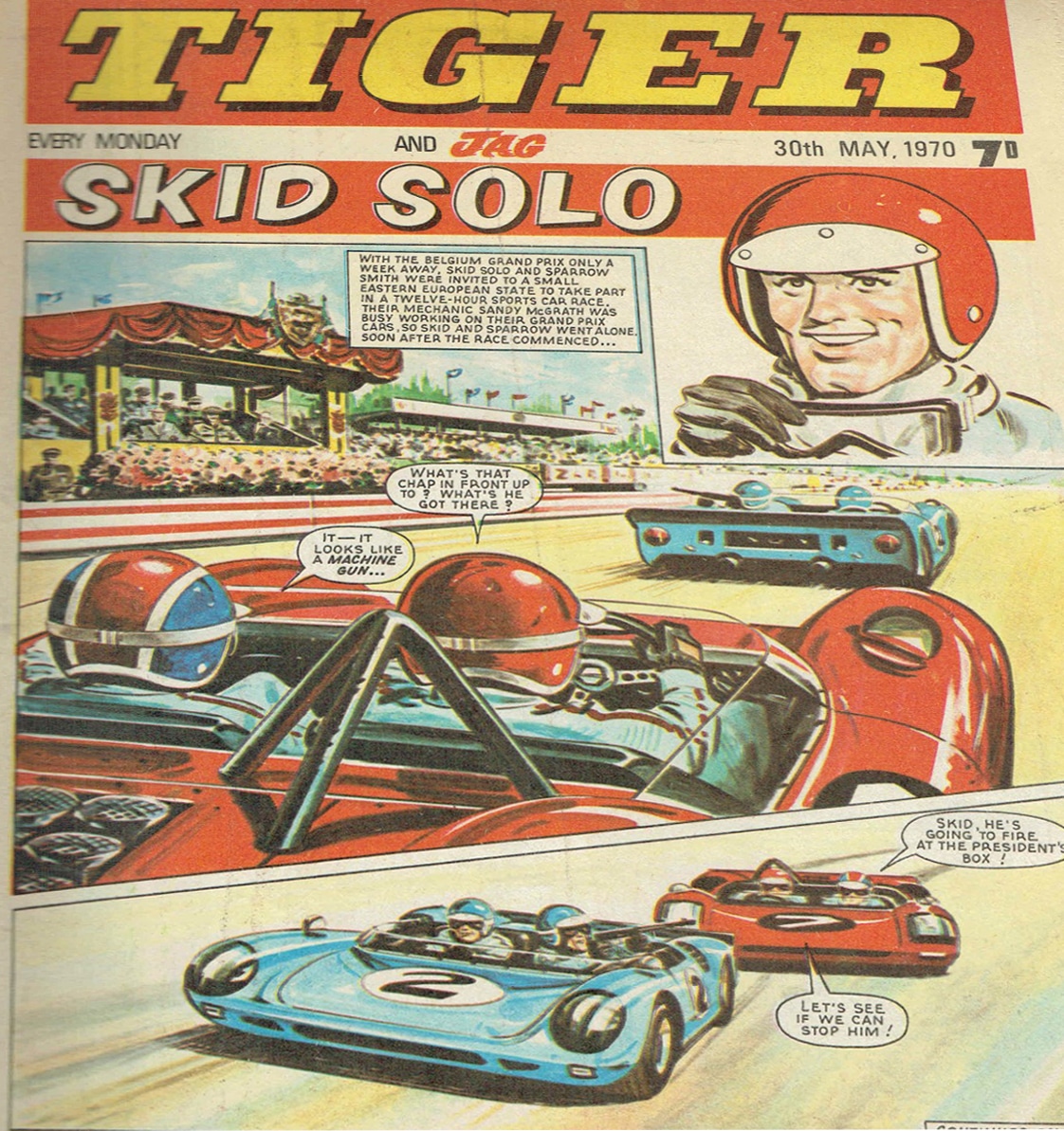

Terror on the race track in 1970

Solo’s wins and titles continued apace – but there was injury and tragedy, too: he would be badly hurt in a testing accident caused by an errant dog, and Sparrow’s big crash would prove fatal.

These doses of ‘reality’ were leavened by an inevitable silly season as his creators sought to keep Solo gainfully employed between grands prix. He could be whisked behind the Iron Curtain or to a potentate’s tropical island, where he would foil a presidential assassination attempt (using his racing car as a weapon) or test a prototype flying car (over an erupting volcano).

There was a strong hint of Bond, as well as Moss, to Solo.

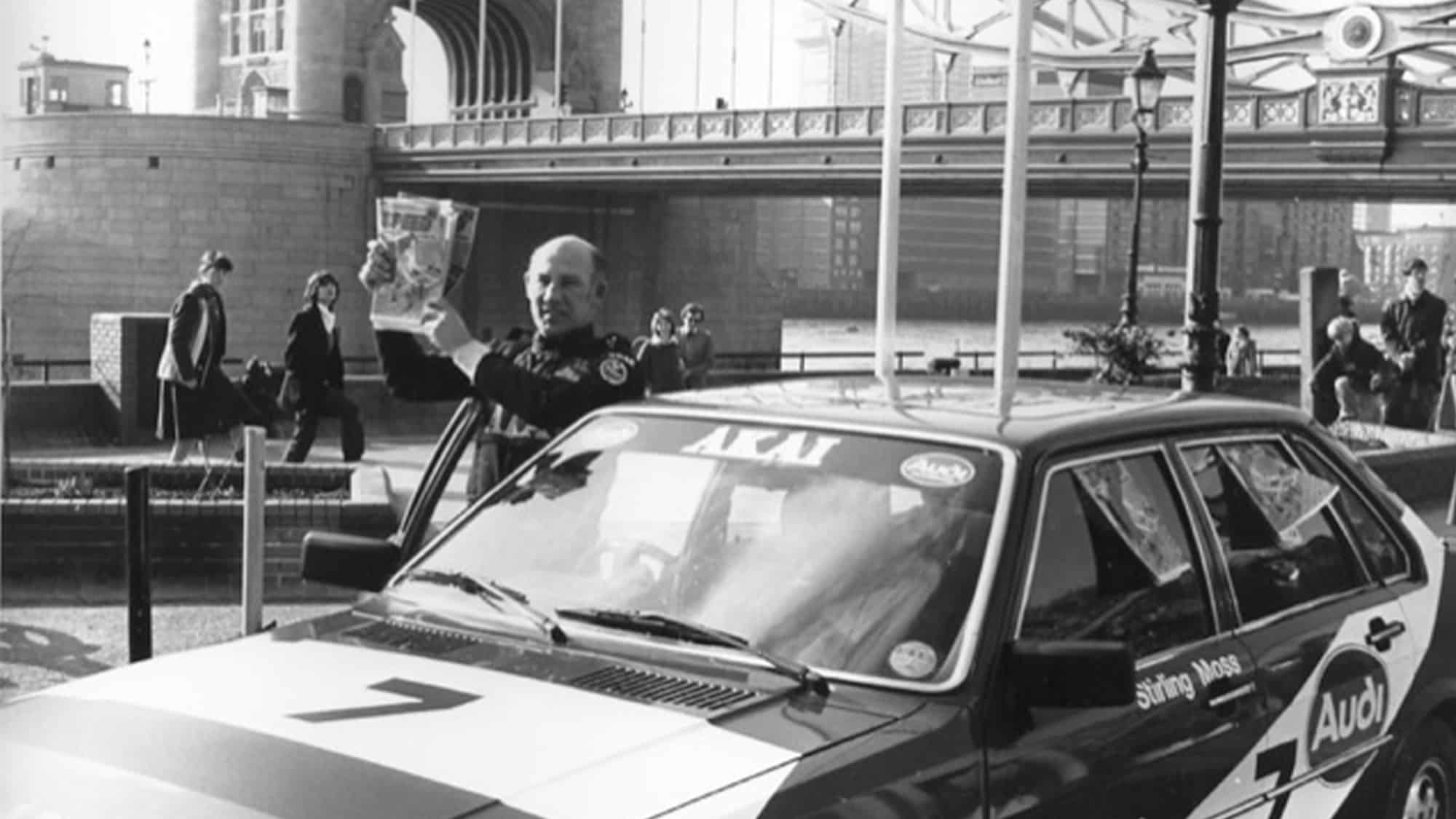

“Stirling was a keen fan of the comic,” says Tomlinson. “When I launched [the sadly short-lived] Speed at a hotel near Tower Bridge, he arrived in his [BTCC] car, at speed, carrying the first copies. He also agreed to appear in a Skid Solo storyline.

Moss with the first copies of ‘Speed’

Barrie Tomlinson

“I found that Tiger’s reputation was such that I could ask anybody – the Duke of Edinburgh, Sir Alf Ramsey, Morecambe & Wise – to do anything, and usually they agreed without it costing us anything.”

Weekly circulation was 300,000 at its peak.

Moss and Solo team up in the BTCC

It couldn’t last, of course, neither for me nor for Tiger.

My interest in it began to wane in 1975 when I received an Autocourse annual for Christmas. Turns out there were real F1 heroes.

So Solo pressed on without me – he made a Niki Lauda-like comeback at one point – and his demise passed me by.

The end was dark, an accident in 1982 leaving him at death’s door and a nation glued to updates in another nod to Moss.

He survived but clearly had been disfigured; readers were prevented from seeing Solo’s face as the loyal Sandy wheeled him into a greyscale sunset.

The harsher truth was that Solo had dipped in the readership stakes. Change was due. The bottom half of the last page of his final instalment extolled the virtues of the following week’s new-look Tiger – oh, and KP’s Griddles crisps.

“Every time a reader wrote to us, we asked them to name their favourite character,” says Tomlinson. “A big chart on my wall tracked their popularity.

“I have always said that one of my more difficult editorial decisions was to drop Skid Solo. But I didn’t have any choice: he was not as popular as he used to be.

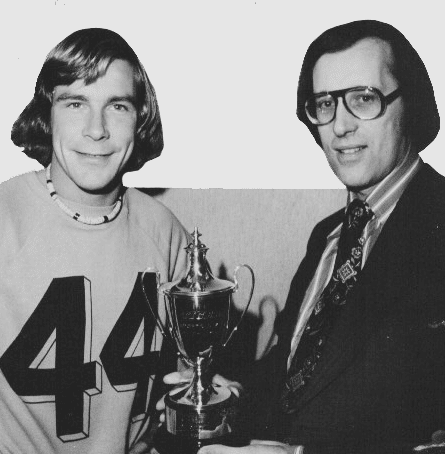

“But he had been very popular. Three times readers voted a racing driver as their favourite sports star of the year: Jackie Stewart in 1972 and 1974, and James Hunt in 1977. When you consider the competition from football and cricket…

“It was not a quick decision. I debated with Fred how to end it and we decided to make it dramatic rather than have him fade out.”

Tomlinson presents James Hunt with the 1977 Tiger Sports Star of the Year trophy

Barrie Tomlinson

There came the inevitable outcry and a subsequent editorial by Paul Gettens – Tomlinson was Group Editor by this time – attempted to pour oil on troubled waters:

Many of you have written to me about the ending of the Skid Solo story, saying you thought it was too sudden. Well, unfortunately, motor racing is like that, being such a hazardous sport.

But very shortly we will be bringing you a tribute to Skid [a single page] and giving you a report on how he is progressing [walking, with a limp, but far from race-ready].

Motor racing was indeed like that still, as fan-favourite Gilles Villeneuve’s fatal accident that same month at Zolder proved so horribly. Reading Nigel Roebuck’s heartfelt appreciation of the brilliant French-Canadian in Autosport caused me to question my devotion to the sport.

Then, of course, I became blasé during 14 years of relative safety…

When researching this article I discovered a remarkable coincidence: Solo’s accident occurred in the early laps at Imola. Lagging in the F1 points, he was leading from pole and perhaps pushing too hard in an unsorted car.

The magazine carrying the story was dated 1 May.

Tiger folded as a separate entity in 1985, though its name continued for a time as second billing on Tomlinson’s relaunched Eagle.

“In the early days the most important thing for a young lad was to have his comic delivered,” he says. “That faded in importance as competition from computer games and TV increased.

“But I still receive lots of messages from people telling me how much their comics meant to them. That’s very rewarding after all this time.”

Three-and-a-half new pence well spent. Thanks, Barrie.

Thanks to Tilleys Vintage Magazines, which assisted with images for this feature