Yes it absolutely should have won in 1969 and were the final fight not between a mismatched Jacky Ickx for Ford and Hans Herrmann in the Porsche, won it surely would have done. But it did win duly in 1970 and that was that.

Its current tally of 19 wins is unapproached by any other manufacturer. But even that doesn’t really reveal how good Porsche is at winning Le Mans. So let me put it another way. On the 20 occasions Porsche has raced as a works team at Le Mans since that first win, it has won 13 times, and that’s not including the works-backed Dauer victory in 1994, nor either of the Joest victories in in 1996 and 1997 with the WSC-95 lent to the team by Porsche for the first of those races and retained thereafter.

On three of the remaining four occasions where neither a Porsche entered nor Porsche supported team won, works Porsches came second on three occasions. This leaves the 2014 race alone as the only Le Mans in the last 53 years which a Porsche has entered with substantial factory backing of one kind or another and not come home in one of the first two places. When it comes to LeMans, Porsche really is in a different league to anybody else.

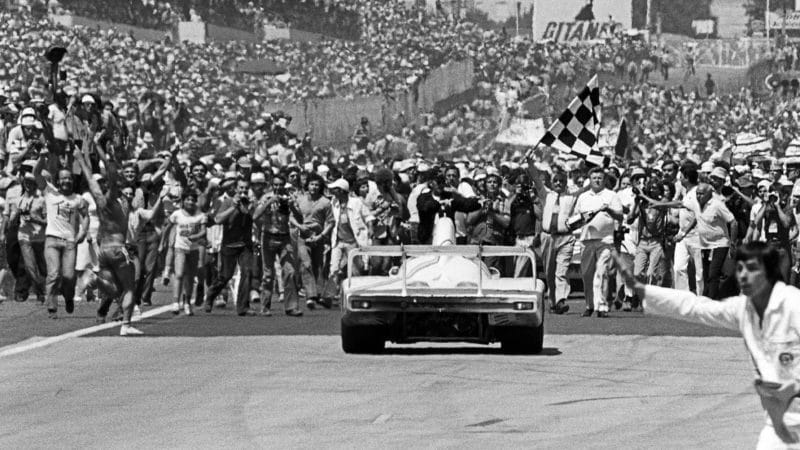

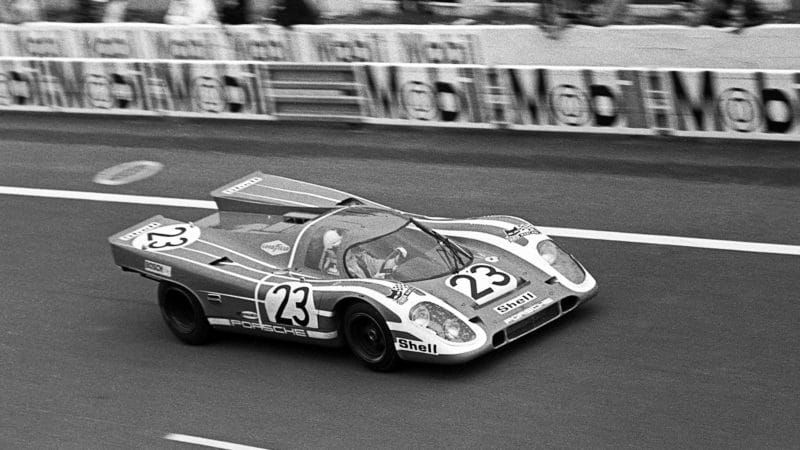

Richard Attwood pilots Porsche 917K at 1970 Le Mans

Getty Images

What’s the secret? I think most worryingly for those who try to rival Porsche, the truth is there isn’t one. I can’t think of one of those wins where Porsche brought some new technology to the table and blew everyone else away with it. It’s true it can get very cute with the rules: as legend recalls no one actually expected Porsche to make 25 917s in order to homologate the car in 1969; the GT1 of 1996 was not exactly within the spirit of regulations either.

The wheeze I particularly enjoyed concerned the suspension of the 911 RSR in 1973. Porsche wanted coil over springs fitted but the rules mandated that the original springing medium – in this case torsion bars – be retained. So Porsche just left the torsion bars in place, fitted the coils as well and then made so stiff the bars were rendered entirely redundant. The rules just said the old springs had to be there, they did not say they had to have a meaningful function…