For the wider world memories of the French ’99 enduro are probably focused on flying Mercedes: the new CLR LM-GTP prototype flipped no fewer than three times through qualifying, the morning warm-up and then the race before the German manufacturer parked its remaining car. Sports car aficionados, however, will recall a classic confrontation between BMW and Toyota. It was a battle fought between the two brands twice over.

The first Toyota v BMW confrontation lasted into the early hours of Sunday morning and was a duel between the Toyota GT-One shared by Allan McNish, Thierry Boutsen and Ralf Kelleners and the BMW V12 LMR driven by the Schnitzer-run factory team’s lead line-up of Tom Kristensen, JJ Lehto and Jorg Muller. Neither would make the finish, and when the Bimmer retired in the 21st hour the race suddenly became a straight fight between the remaining entries from the two manufacturers. The BMW shared by Pierluigi Martini, Yannick Dalmas and Jo Winkelhock ultimately prevailed in a climatic and controversial finish to the race.

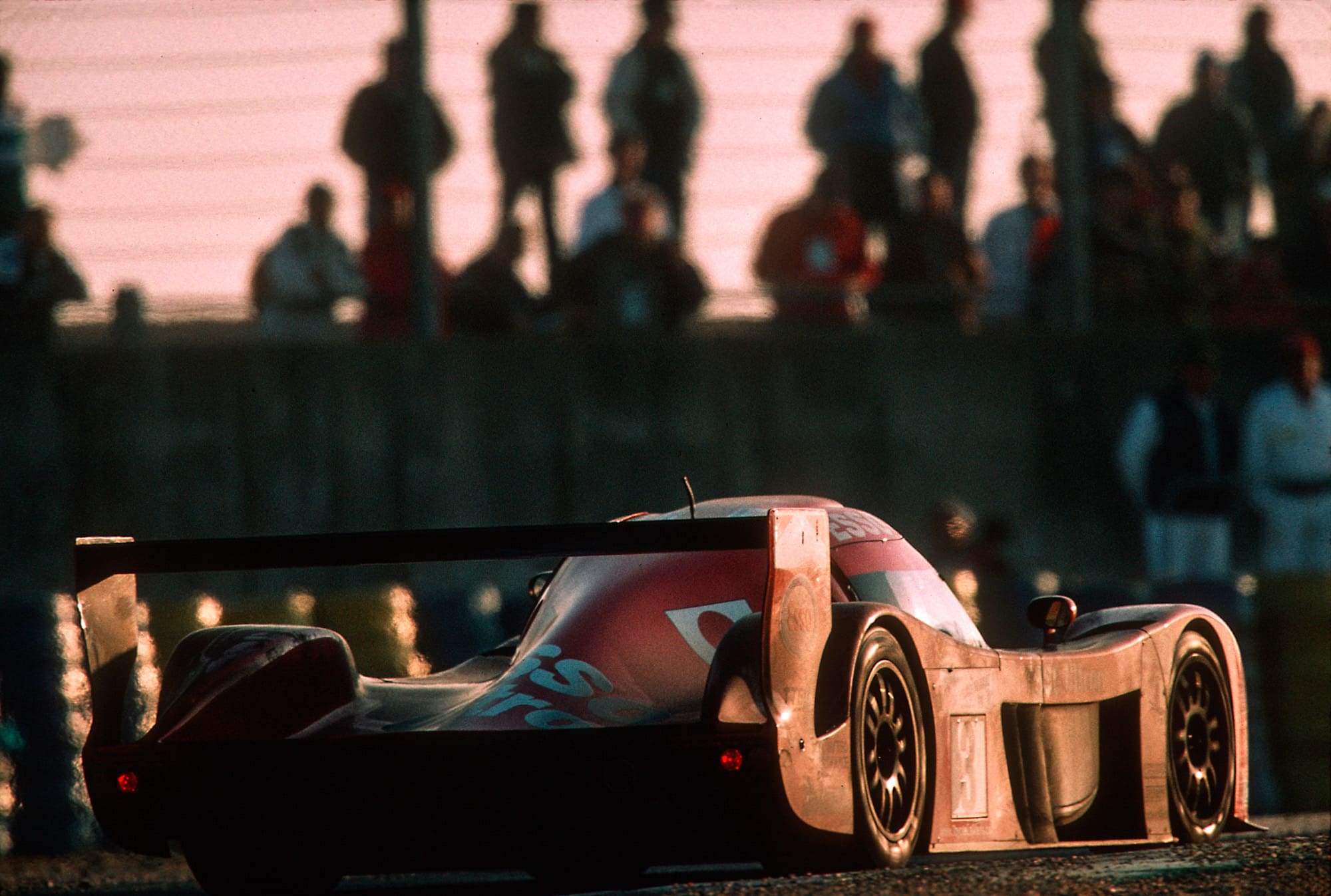

Martini teamed up with Frenchman Yannick Dalmas and Joachim Winkelhock of Germany for 1999 Le Mans win

Getty Images

It was the latest — and not the last — near-miss for Toyota in its quest to win Le Mans, which wasn’t finally fulfilled until 2018. The GT-One was a goal-post moving design initially developed to the GT1 rulebook, which made it a road car in theory rather than spirit.

It hah already lost a clear-cut chance to win Le Mans on debut in 1998. The car shared by Boutsen, Kelleners and Geoff Lees had come within 80 minutes of victory. The car had already needed two changes of its gearbox internals, but still had a narrow advantage over the chasing Porsche 911 GT1-98s as the race drew to a close when the transmission problems struck again. There was no oil left in the ‘box this time, the resulting temperatures leaving no scope for another repair. It may or may not be true that the sump plug had not been correctly replaced at the previous stop for a replacement of its gear cluster.