Forced by financially straitened Clement-Talbot’s subsequent withdrawal to join Alfa Romeo’s ranks for 1933 – well, if you can’t beat them – Fox’s tight-knit team scored yet another third place before switching to a Singer for the following year and finishing seventh.

Seeking an uptick in competitiveness, Fox renewed the relationship with Lagonda that had opened his Le Mans account: a retirement in 1929 due to head gasket failure.

The Staines-based company was on its uppers, too, but the enthusiastic Fox persuaded it to supply, via agents Warwick Wright, three ‘lightweight’ and uprated versions of its M45 Rapide for the 1934 RAC Tourist Trophy, a handicap race at Ards that eschewed supercharging.

They finished fourth, fifth and eighth – a solid result befitting the equipment. Powered by Meadows’ 4.5-litre pushrod ‘six’ – good for 140bhp at 3600rpm in tweaked form – torque was the watchword for a car that weighed over 1500kg still. Two were entered for Le Mans in 1935 but few expected them to deny Alfa’s lithe and lissome, supercharged 8C a fifth consecutive victory.

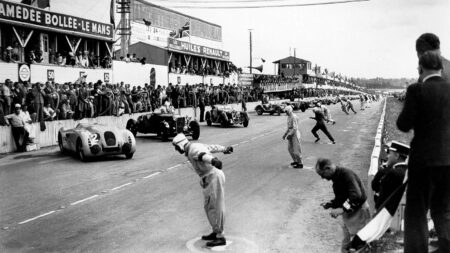

Lagonda M45 of Luis Fontés and John Hindmarsh at Le Mans, 1935

Getty Images

Fox’s driver selection was intriguing. Hawker Siddeley test pilot Johnny Hindmarsh was a known quantity: an affable, capable and reliable team player who looked much older than his years and who had finished fourth for the team in 1930 and co-driven its Singer in 1934. Co-driver and fellow flier Luis Fontés could not have been more different. Gawky at 6ft 2in and sporting thick-rimmed spectacles, this illegitimate son of a Brazilian shipping tycoon and British mother looked every inch the student that he had so recently been: an alumnus of Loughborough Engineering College not yet 23.

Suddenly flush with the family fortune, his apparently hot-headed, last-minute hiring of John Cobb’s 8C ‘Monza’ for the 1935 JCC International Trophy at Brooklands in May caused a stir such was his inexperience: he had recorded RAC TT retirements in an MG and Invicta. His victory – the product of measured, sustained speed attained in shirt-and-tie and minus headgear – was a sensation. So, too, was his bacchanalian party in celebration. Those looks deceived in more than one way.

At the end of the same month and in the same car – now in his ownership – Fontés finished third behind a pair of faster, more modern Bugatti Type 59s in the Isle of Man’s Mannin Moar: a gruelling 200-miler on a demanding road course. Fox, for whom money was secondary to talent in such matters – though oodles of cash never hurt – had seen enough to be convinced. Hindmarsh, however, would be trusted with the opening stint.