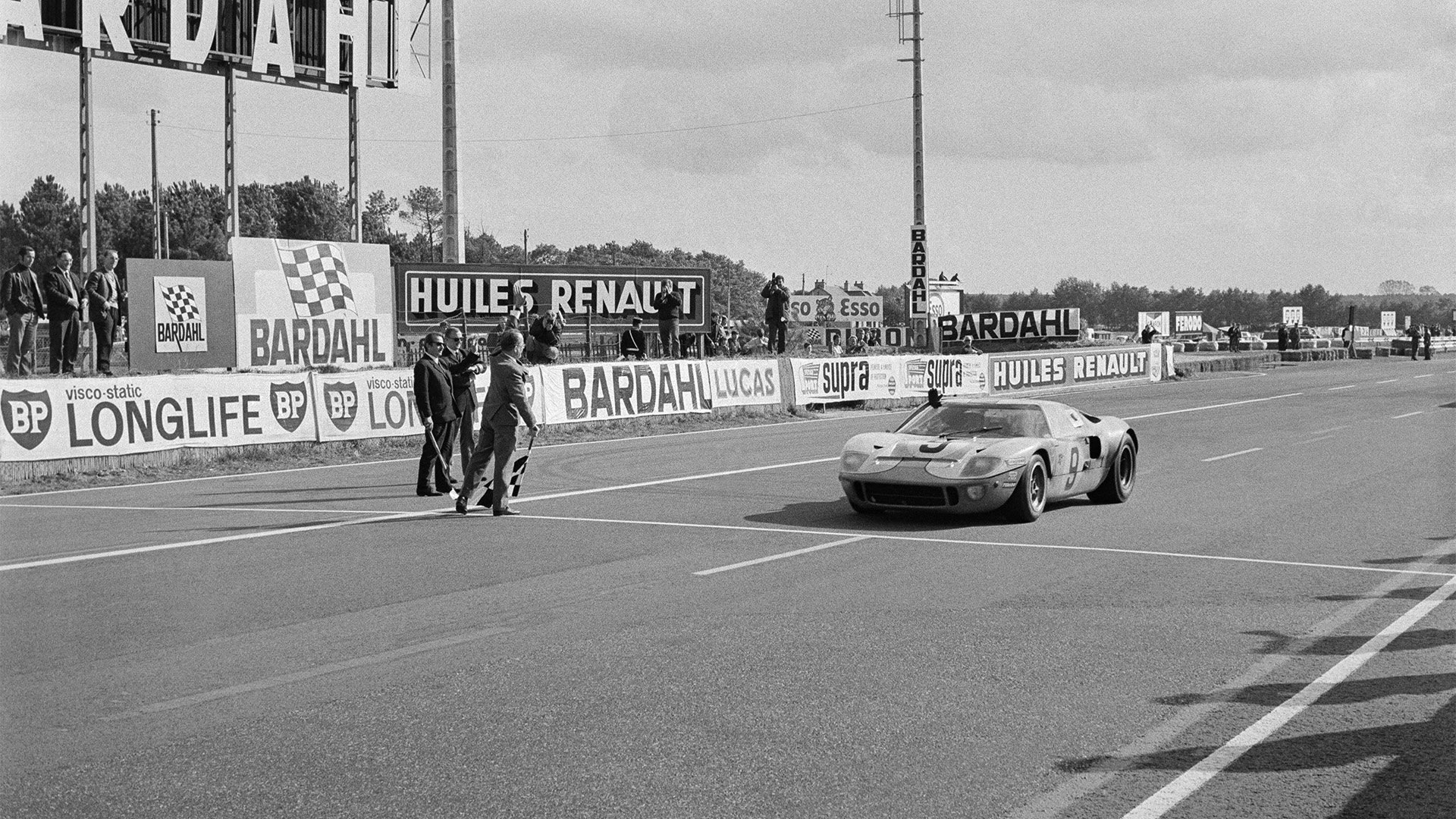

Henry leaves, gets the GT40 done and duly uses it to kick Enzo’s ass all the way from Le Mans to Maranello. Ford then duly won the French classic four times on the trot, while Ferrari would have to wait until 2023 for its next taste of victory. Ass kicked. Job done.

But as I will be by no means the first to point out, history tends to be written by victors naturally inclined to, if not make stuff up, then certainly put their best foot forward; accentuate the positive; put their own, unique spin on proceedings.

But the real story, while a little less flattering for Ford when it is realised the massively resourced factory teams only won twice in the six years GT40s and their derivatives raced in France, is I think rather more interesting than the wham-bam bare bones outlined about. Not least because it doesn’t start in 1964 nor even with a Ford.

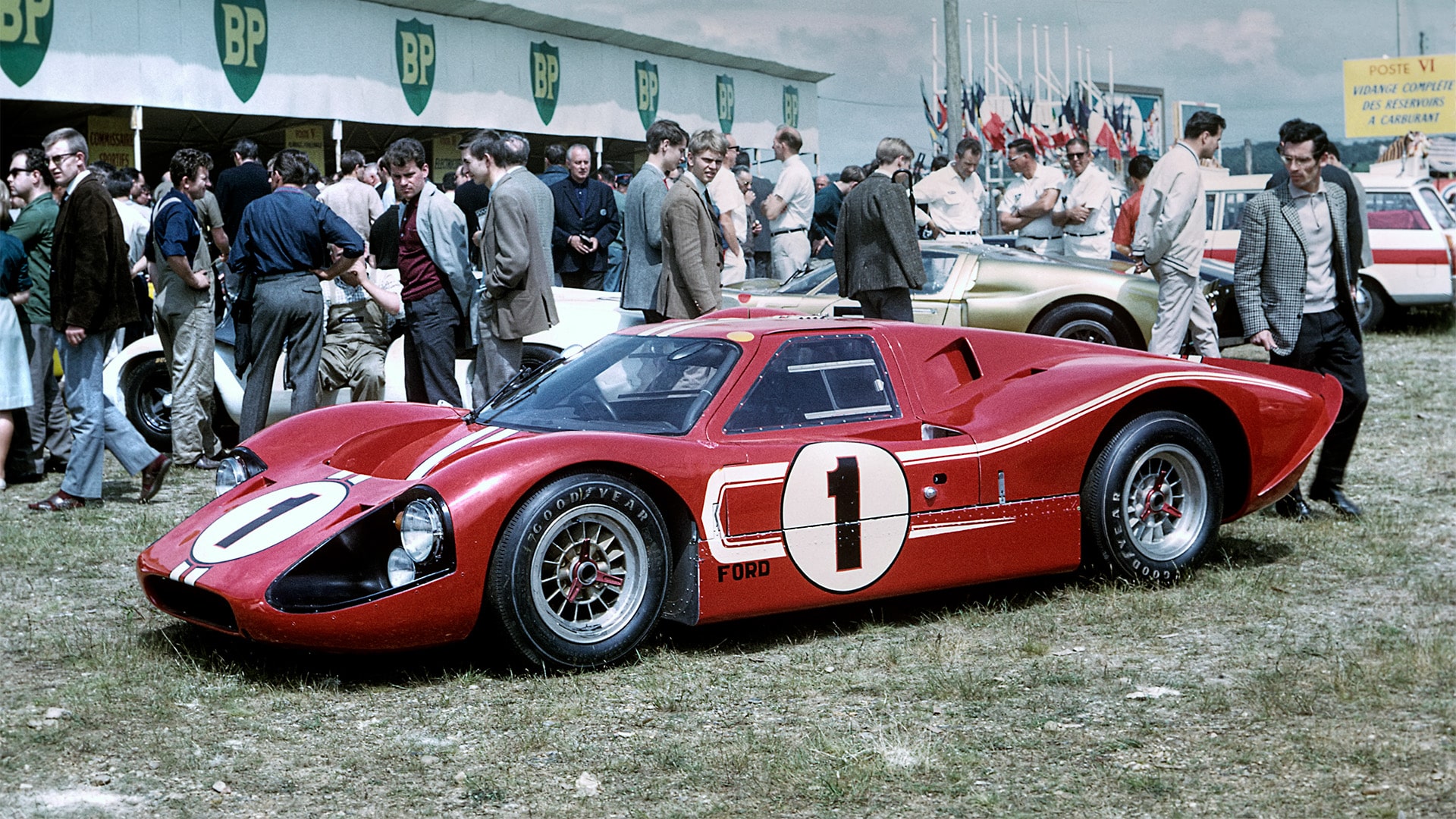

Prior to a picture perfect Le Mans in 1966, Ford’s true story began two years earlier

Getty Images

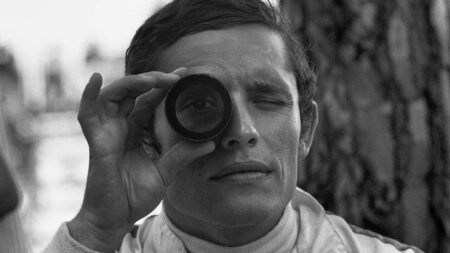

If Ken Miles was the unsung hero among the drivers in the GT40 story before Le Mans’ 66 got made, then to this day the Lola Mk6GT is the equivalent among the cars.

The decision to create the car that became the GT40 was made in 1963 with a view to it being at Le Mans the following year. For a brand-new car from a company with zero experience in building anything like what might be required, it was more of an impossible dream than an ambitious target. The Lola, and its creator, Eric Broadley, saved not only Ford’s face but its own bacon too.

By the summer of 1963 various design studies had made it clear Ford stood zero chance of getting a new car to Le Mans the following year. But in a moment of true Blue Peter worthiness, Broadley provided one he’d made earlier. The Mk6 was a make-or-break car for Lola and just as it looked like breaking it, it made it – just not in a way that could have been imagined at the time.

Broadley had thrown all the money, time and talent into the project that the then-tiny Lola concern could muster. The result was the first mid-engined sports car to use an American V8 engine, pre-dating even the Lotus 30. It had monocoque construction in an era of space frames, and it was light, slippery and potentially very fast indeed.

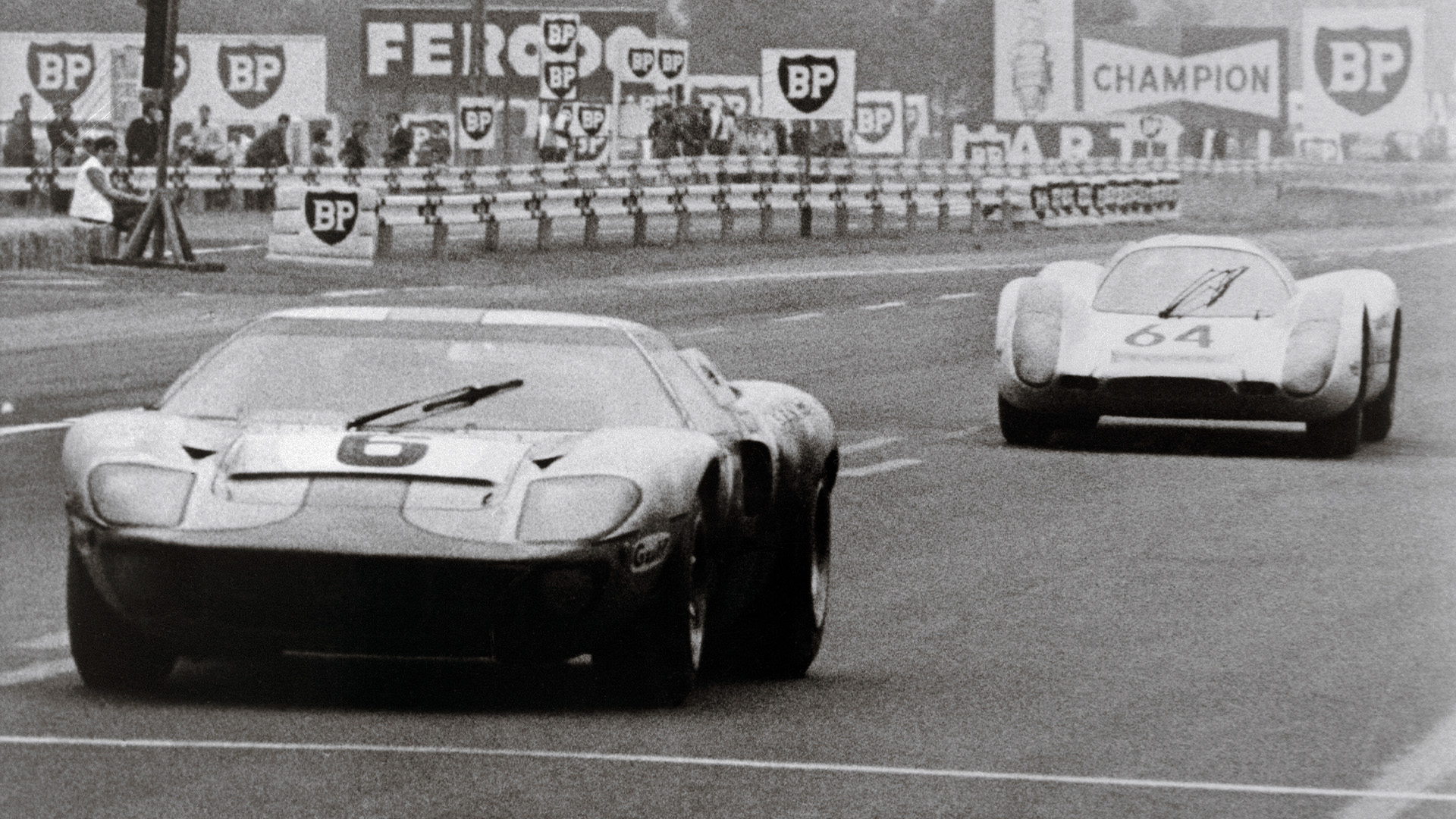

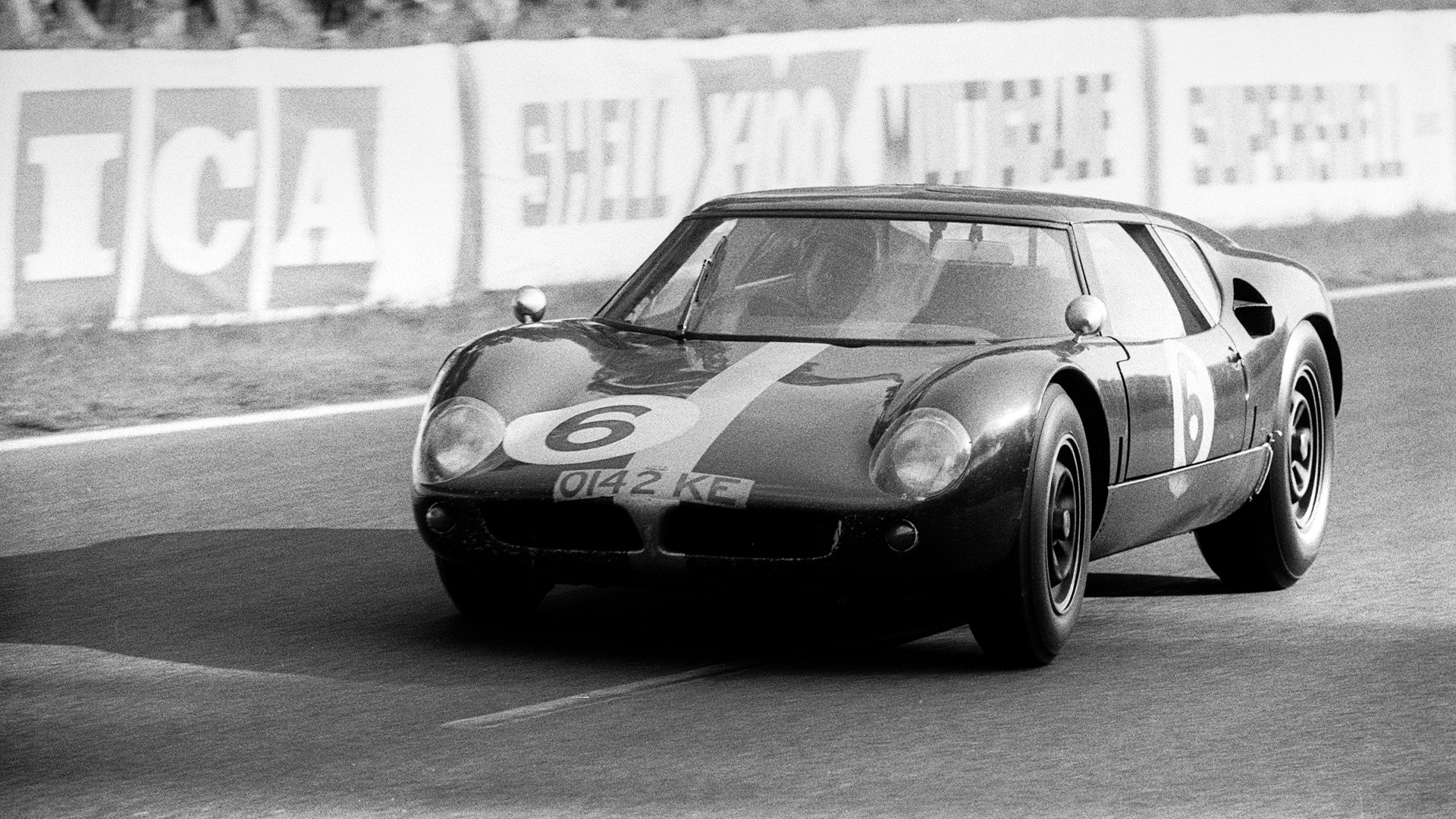

A hint of what was to come: The Lola-Ford Mk6 GT at Le Mans 1963

Getty Images

But it took so long to prepare for Le Mans that drivers Richard Attwood and David Hobbs had to leave for France without it, Broadley himself driving it down, arriving too late for scrutineering and having to beg not to lose its place in the race.