Lyons was a businessman first and foremost. The selling of thousands of thoroughbred sports cars in America on the back of success in the only European race with cachet Stateside was his focus. He was happy to admit that Bill Heynes – a valued employee since the pre-war SS days and now his Technical Director and Chief Engineer – had been right. When quickly he realised that Hollywood leading man Clark Gable was far from alone in lusting for one, he was sold: Le Mans became Jaguar’s most important showcase of the year.

Three privately entered and mildly modified XK120s were its toes in the water of 1950. That of Leslie Johnson, co-driven by Bert Hadley, ran as high as second for a brief time and was holding third place when its clutch failed after 20 hours. The others, plagued by braking issues, finished 12th and 15th.

Lyons went all in for 1951 – the ‘world’s fastest production car’ really needed to win – by commissioning a Competition version to suit the demands of this race above all others. Only the fabulous 3.4-litre XK straight-six and front suspension was carried over, as Heynes designed a taut spaceframe upon which aerodynamicist Malcolm Sayer draped bodywork only slightly less slippery than it was sensual. Built in secrecy, the C-type caused a sensation – as Jaguar unveilings tended to do.

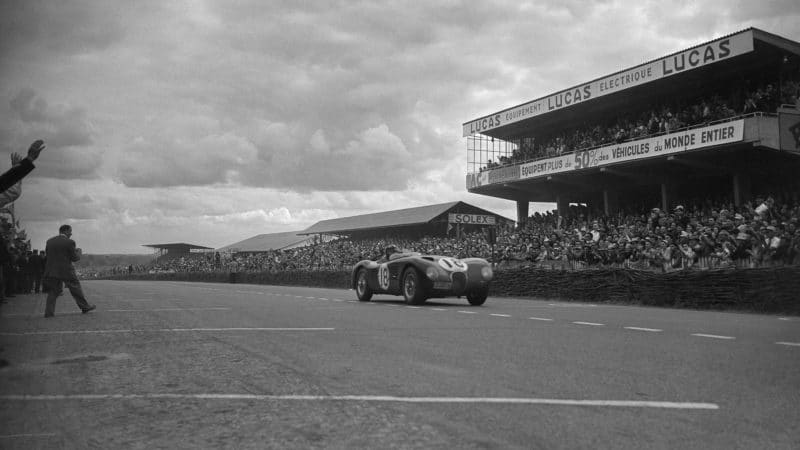

Stirling Moss at the wheel of a Jaguar C type competing at Le Mans in 1951

Getty Images

Stirling Moss – revelling in his first works gig and as proud as punch to be driving a British car that was so “futuristic and potent” – rushed into a lead that he and co-driver Jack Fairman held until a copper oil pipe in the sump fractured and ran the bearings dry just after midnight; a sister car had suffered the same failure. Fortunately, the remainder, opposition already pummelled into submission, was able to reduce its pace and still win, courtesy of Peters Walker and Whitehead–and by nine clear laps having set a distance record despite 16 hours of rain.

But for the shockwaves caused by Moss’s bombshell telegram after the 1952 Mille Miglia – Must have more speed at Le Mans. Stop – there is good reason to believe that Jaguar would have scored a second consecutive win at Le Mans. Instead, rushed alterations – when perfecting disc brakes should have been the priority – proved calamitous: all three cars boiled to death in the first quarter. (A fortnight later Moss won at Reims in a privateer car wearing discs: a world first.)

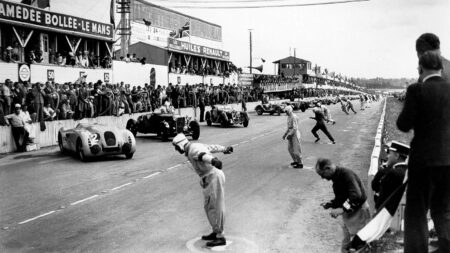

Scuderia Ferrari was in the Le Mans mix by now, as was Mercedes-Benz. The latter had come, seen and conquered in 1952, but the most competitive (in theory) field yet assembled compensated for their absence from 1953: Alfa Romeo, Aston Martin, Cunningham, Ferrari, Gordini, Lancia and Talbot-Lago all had their eyes on what had become a global prize.

An all-star field takes the start in 1953

Getty Images

Yet Jaguar blew them all away: first, second and fourth, using fully sorted ‘lightweight’ C-types fitted with Weber carburettors in place of SUs, plus servo-assisted Dunlop disc brakes. Moss again led but would finish second after a delay caused by a blocked fuel filter. The victors were war heroes Tony Rolt and Duncan Hamilton, who brushed aside the discomforting buffering caused by a broken aero-screen to win by four laps.

This same charismatic pairing was to the fore in 1954, too, albeit this time in a Jaguar that had given up all pretence of aping the look of its road-going cousin. The new D-type was a mix of blue-sky thinking by Heynes and Sayer and red-pen accounting: its monocoque centre section and aeroplane-on-wheels shapes and lines were attached to and underpinned by as much of its predecessor as could be repurposed, including an engine which was now dry-sumped.