Carroll Shelby: The lost interview

When motor racing legend Carroll Shelby visited Goodwood 25 years ago, David Waldron met him as part of his research for a book project. The conversation has never been published – until now…

Getty Images

Chatter, the clatter of plates and children screaming doesn’t amount to the ideal soundtrack when you’re trying to interview a legend. But that’s the background distraction I faced when I met the great Carroll Shelby in a hotel lobby during his visit to the second Goodwood Revival back in 1999. Still, it didn’t perturb the tall, rugged Texan, then 76 years old, whose impressive physical presence belied an open and friendly nature.

The Le Mans winner, ace tuner and former chicken farmer had travelled over for a celebration of Aston Martin’s 1959 World Sportscar Championship, clinched at Goodwood almost exactly 40 years earlier. Shelby, who died in 2012, had agreed to an interview for a book I was working on about Le Mans winners, and he answered all my questions without holding anything back. As you’ll see we covered a lot of ground, and he’d forgotten nothing of the three and a half years he spent masterminding Ford’s victorious assault on the 24 Hours. When we parted company he shook my hand warmly and told me to contact him if I needed anything further. What a privilege.

The book never materialised and the interview has remained unseen and unpublished during the intervening 25 years. Here it is…

Shelby had a long association with Goodwood, starting in 1959; 40 years on, he was back at the Circuit for the Revival – where this interview was conducted. He returned to the Revival in 2000, too – and saw a Shelby Daytona Coupé on track

Getty Images

Motor Sport: Your first Le Mans drive was in 1954 with Aston Martin and yet you didn’t come back to the race until 1959, the year you won. Why didn’t you return to Le Mans earlier?

CS: I was racing in the States and getting more experience over there than I could have got here. I was also able to stay closer to my family for part of 1955. I could have gone to Le Mans, but it wasn’t high on my priorities because, although I wanted to win the race, I didn’t feel that Aston stood much of a chance. In 1956, Ferrari offered me a seat in their sport cars. I turned that down because I was still interested in spending as much time with my family as I could. I had a good situation in the States financially, racing practically every weekend, so staying in the USA was the best option because I had businesses there too. In 1958 I came over to drive for Aston but I got sick and didn’t race, so I decided to do it in ’59.

The Shelby American team busy themselves at the 1963 Daytona 3 Hours with the Cobras of Dan Gurney (No98) and Skip Hudson (No97)

Getty Images

When you began the AC Cobra project you were quoted as saying, “The reason I did it was to kick Corvette and Ferrari’s asses!”

CS: Nah, that’s not right! Firstly, AC was a subcontractor and the car was the Shelby Cobra, never the AC Cobra, which journalists loved to call it. It was homologated as a Shelby American Cobra. I started making it because I’d always wanted to build my own car. My ambition was to construct a car that could beat the Corvettes.

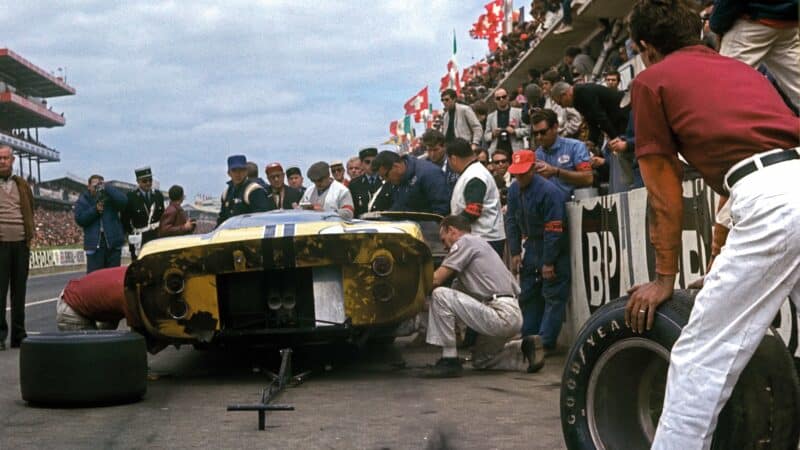

Gurney and Bob Bondurant’s beautiful Daytona Cobra Coupé, Le Mans 1964.

Getty Images

Hadn’t you proposed a similar project to General Motors?

CS: Yeah. I put a deal together with Ed Cole [Chevrolet general manager] and built three cars in Italy on Corvette chassis, but it all became very political on GM’s side, and I was forced to give the Corvette project up because Zora Duntov [engineer who transformed the Corvette into a high-performance car] wasn’t happy about it: that’s when I started looking for an alternative.

“I’d always wanted to build my own car. My ambition was to beat the Corvettes”

I heard about a new Ford engine, and around the same time I learned that AC had lost their Bristol engine. They were using an old six-cylinder Ford that was unsatisfactory. I talked to the Hurlock family that owned AC Cars about shoehorning the new lightweight 4.2-litre Ford engine into a beefed-up AC chassis and we reached agreement. I went to Ford and secured a couple of engines. In addition, I met Lee Iacocca [from Ford’s marketing arm] and got a little money; I also met a young guy called Ray Geddes who was new to Ford’s financial department. I told Ford I needed someone to look after the management side as I was going to build cars, so Geddes and I formed a partnership. We had to build 100 units to give Ford a production car to compete against the Corvettes. We succeeded and we realised that the car could come to Europe to race so we came over to Le Mans in ’63.

We soon understood that the drag coefficient was too great and we started working on the Daytona Coupé. We could very easily have won Le Mans outright with it in 1964, but a hose came loose on the oil cooler: but we still won the GT 4001-5000cc category.

from left: Shelby, Bondurant and Jochen Neerpasch with Shelby’s Kammtail creation

Getty Images

I was working on the Ford GT programme at the time and Ford decided to push on with that project. They’d been unsuccessful so we moved most of the work to the United States and came over in 1965. Ford built the engines. Unfortunately, we got some bad head bolts and all the engines blew up in the opening hours of the race.

“The press quoted me: ‘Ferrari’s ass is mine.’ I never said it although I did want to beat his ass”

Henry Ford called in Leo Beebe [Ford executive], myself and a few others in September ’65. He was there with his wife and his young son, Edsel. They’d wondered what was going on because Ford couldn’t make a better showing. Mr Ford had some little nametag-like things made up for us to wear that said “Ford wins Le Mans in 1966”. That scared us! We left the room, walked down the hallway, then walked back in and asked him what the fiscal restrictions were. All he said was, “You probably won’t have a job if you don’t win Le Mans in 1966!” That was the first of the really big money spent by factories in racing outside of Mercedes in 1954 and ’55 on the grand prix project.

Ford’s attempt to buy Ferrari failed so they decided to build their own car. Ray Geddes and I came over to England and made a deal with Eric Broadley [owner of Lola Cars], bought his car, hired him, hired John Wyer, put the programme together and they started constructing the car. Broadley fell out of love with Ford pretty quickly because of the bureaucracy and the politics. I don’t blame him! John Wyer and Len Bailey carried on building the car. In 1964 they began putting it together and saw it was fairly competitive. We scored our first victory at Sebring in the GTP category in 1965.

Lola Mk6 GT, the basis of Ford’s GT40, Le Mans 1963

Getty Images

But you had major problems at Le Mans during the 1964 April test weekend because the car was basically a disaster.

CS: Aerodynamically it was horrible. At that time I was concentrating more on the Cobras than on the Ford GTs. In 1964 Ford came to me and said they wanted us to play a more active role in the Ford GT project, so I got heavily involved at the end of the year.

In 1964 you won the GT 4001-5000cc category at Le Mans beating the Ferrari 250 GTOs – a big satisfaction for you.

CS: I didn’t set out to beat Ferrari especially, but he [Enzo] was competition so we wanted to beat him. When he supposedly got Monza cancelled, the press picked up the incident and quoted me as saying, “Next year Ferrari’s ass is mine,” which created hard feelings between Ferrari and us. I never said it although I did want to beat his ass! I let things go along because it gave us a lot of press coverage.

He really had some hard feelings in ’65 and ’66 when we got serious at Ford. I’d turned him down as a driver and he made some snide remarks. I always respected Ferrari. He was a hard-nosed old guy, but he accomplished a lot after the war with very little and I respect that. But I didn’t at all admire how he treated his drivers as Fangio very aptly stated; the way he created animosities and so forth. I was real good friends with Luigi Musso and spent three months with him before he was killed. Musso and [Eugenio] Castellotti were friends and I saw Ferrari go to one and say, “What’s your problem with Castellotti?” and then go to Castellotti and say the same thing about Musso and both these guys were killed.

Ford V8 in the Cobra 289 Roadster, 1964 Targa Florio

Getty Images

I’d never say that Ferrari caused that, but a lot of people thought so. He did the same thing to some of the other drivers; it was his way of goosin’ them up and putting them on the edge, because he thought he’d get a sharper driver out of it. I never had to do that. I think a race driver has a desire to win or he doesn’t, or he has the heart to win or he doesn’t and you don’t have to pull stuff like that. So while I might have disagreed with some of the things he did, I also admired his accomplishments. It was just a section of the press that created antagonism between us.

Let’s come back to Monza 1964 and the cancellation. There were three races left, Monza, Tour de France and Bridgehampton. The Tour de France was a foregone win for Ferrari. Bridgehampton was a Cobra circuit. So Monza was going to make the difference.

CS: We had six Daytona Coupés ready and we could have easily beaten the GTOs. I feel that we would have won without any problems in ’64; we didn’t so that’s history. I don’t think that what he did was kosher, but so what!

Shelby shares his thoughts at Le Mans ’64 – but Ferrari would prevail with a 1-2-3

Getty Images

What do you think gave you the edge over the European manufacturers?

CS: What most people didn’t realise was that at the time the European formulas were based on smaller engine displacements. We had V8 engines that you didn’t have to stress to outperform the European engines of that era. Mr Ferrari chose to run with 3 litres instead of 4, which he had at the time. In 1965 the Ferraris were running 4-litre engines all the time in their cars, but we could beat them anyway so it didn’t make much difference.

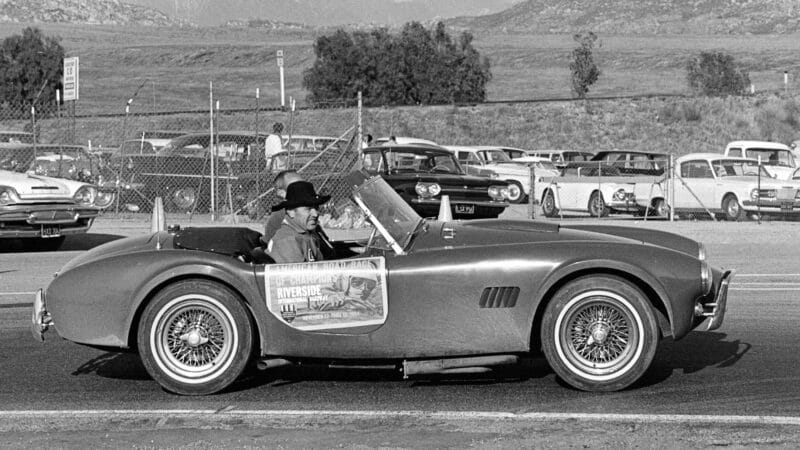

Shelby, later in the year – with hat, of course – at California’s Riverside 200 to see a team win

Getty Images

Another area in which the Europeans were very backward was tyre development, which was very lucky for us! They didn’t believe in the tyres growing wider and wider. Goodyear was just getting into the tyre wars and they gave us whatever we wanted. Our chassis was unsophisticated, but you can make any chassis work if you put a lot more rubber on the track than the opposition. Two years later that wouldn’t have worked, but it did in ’64 and ’65. By ’66 when we were racing the Ford GTs against the Ferraris, they all had wider tyres.

So you feel you were a pioneer in that area?

CS: Yeah. In my driving career I’d started using Goodyears in ’58 and I had a good relationship with the top management, so I could go to them and make them spend a lot of money they wouldn’t ordinarily have spent to try to build their reputation quickly, which fitted in with my plans at that time.

Did you make enough Cobras to get them homologated?

CS: Hell yes! I built about 600 289s.

Although you had it homologated for racing, some say you didn’t have the required number of cars built at the time.

CS: We homologated the 289s. We had over 200 cars under construction at AC Cars and the FIA came and counted them. We had 50 427 SCs built and completed and we had another 50 under construction, but we never completed them so we never homologated them. Ferrari is the one who didn’t build enough 250 GTOs.

“I think museums are the cancer of the automobile racing world”

We built the 289 Cobras and the regulations at the time said as long as we used the same chassis, we could put any body on them we wanted hence the Daytona Coupé. I still take 289 Cobra chassis and put Daytona Coupé bodies on them, but I do it now for another reason. Those six chassis are selling for $4m-$5m and that’s making trailer queens out of them! I think that’s a crappy thing to do as I reckon the cars are there to be raced. I’m building 10 or 12 more Daytona Coupés today on genuine 289 chassis I bought. I build these Coupés because I want them out there racing in these vintage events, as there are these guys who won’t race a car worth $4m or $5m. They just stick it in some museum somewhere.

I think museums are the cancer of the automobile racing world to tell you the truth. I’m not saying you shouldn’t have museums, but they should be for historical reasons. If you have a racing car, I don’t think you should just sit it up on a pedestal and say, “Oh that won this or that won that.” Get out and show it off once in a while the same way I do with my cars. I have a lot of the originals of the different cars I built, and I keep them in driving condition. I don’t have time to drive all of them – I wish I did!

a salute from Le Mans race director Jacques Loste as Shelby’s Aston Martin finishes first

Getty Images

When you won the GT category in 1964, did that make a lot of noise in the States?

CS: It made a lot of noise in the enthusiast publications like Road & Track, but not really outside the motoring press, which was always much more active in Europe than in the States. It got us a lot of publicity. Ford was very proud of it. They wanted to get more sophisticated, which I knew we should, but we were damn lucky to take that old chassis and do what we did with it. This was because, as I told you before, the American V8s were available, while the Europeans were very slow to increase their engine capacity, and also very backward in their tyre development compared to where we were in the States. They were very slow to realise that race cars go faster on wider tyres.

I went to the chairman of Goodyear at the time, and said, “If you make me some moulds to the width of these tyres, we’ll beat hell out of those guys! And we don’t even have to get sophisticated to do it.” I was lucky for a year or two and then the Europeans caught up.

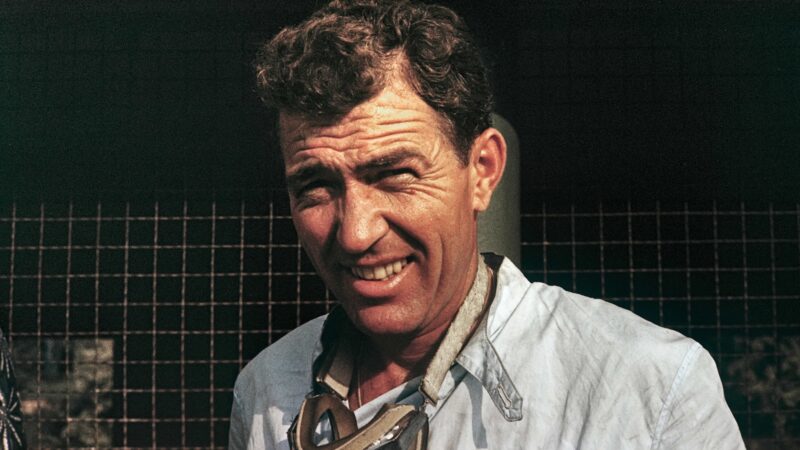

Shelby, Le Mans winner, 1959.

Getty Images

In 1963 when you actually began the GT programme, a guy who drove for you, Skip Hudson, said it was the fact of having two crack drivers at Daytona – himself and Dan Gurney – who got the project off the ground. Was that true?

CS: Skip wasn’t that good; he always out-thought himself! Dan Gurney had the natural ability right off, but it wasn’t Skip’s case. The guys who got the Cobra off the ground were Ken Miles and Davy McDonald. Daytona wasn’t even a big factor in the success of the Cobra. In fact it was a failure there because with the old 289 Cobra it was like pushing a brickbat through the air! So we saw very quickly that if we were ever going to do anything outside the little old circuits in the States, we had to come up with something different.

“We won because Ferrari couldn’t change their brakes; we could”

And that’s when we had Pete Brock sketch up a design and Phil Remington, John Collins, John Ohlsen and Ken Miles went to work. The first time we took that car out to Riverside to test it – we didn’t have a wind tunnel back then – we ran it down the mile-long straightaway. The tufts went up and the ass end came off the ground! So it was about a four-month constant development process of fitting spoilers and revamping the aerodynamics. One of the interesting things is what Pete Brock says in his book about how this famous aerodynamicist told him how we needed to design the car, and he loves to say, “Carroll let me build the car and proved me to be right.” In fact, all we did was use the Kamm effect on the back end of the Daytona. It’s a primitive solution as you cut the ass end off the car and add an air dam.

This aerodynamicist was Benny Howard. He was probably the greatest aerodynamicist before aerodynamics became so vital to the aircraft industry. He was self-taught and all he wanted us to do was to extend the tail like Porsche did with the 917s. So in the end Benny Howard was right and Brock was wrong. But we made it work by fiddling round with air dams. John spent over 1000 hours without a seat on the other side of the car with Ken Miles. They’d stick tufts here, put an aero dam there, and change the slant of the windshield.

Why we won was due to many factors, but one of the main ones was that Ferrari didn’t know anything about aerodynamics either, and he was sold on smaller engines. Also he didn’t realise until very late in life that disc brakes were a hell of a lot more efficient than drums. As I said, I’m not here to criticise Ferrari, but we were fortunate that we were up against him.

Le Mans 1967 was a GT40 fest, although Shelby didn’t appreciate Ford’s interference nor their inclusion of Holman Moody cars as competition

Getty Images

Nineteen sixty-five at Le Mans was obviously a big disappointment. Who was responsible for quality control?

CS: Ford built the engines and bought all the parts for them. It was just one of those things that slipped through the cracks. The quality wasn’t checked at the head-bolt supplier as who’d ever have thought we’d slip up? We built some gearboxes at the airport and one of the best guys in the business, Ian MacGregor, got a lot of flak. But he had to build these first gearboxes too quickly; they wanted to build automatic boxes too, which was a goddamned stupid thing to want to do. We had a lot of help from inside Ford from a lot of people who didn’t know what they were doing.

The guys Ford gave me were more a hindrance than a help! When Henry Ford said in 1965 he wanted to win, we kicked most of them out because they thought they knew what to do, and we brought in a guy called Homer Perry plus Leo Beebe to take charge of the programme. Beebe had been a sales manager and Ford was also Beebe’s wartime commanding officer; he was a very fine administrator and he took the politics out of it. We made only one serious mistake as we brought sprint car drivers to Le Mans in ’67 and a few in ’66 too. We were forced to do that. There’s nothing wrong with sprint car drivers, but they just didn’t know a damn thing about Le Mans and we had to train them. We had Ken Miles, Bruce McLaren and Denny Hulme who knew the problems you have at Le Mans.

Back then you never had enough gearboxes, brakes, engines and you had to take care of all three of them. Those guys understood that and those sprint car drivers didn’t so we lost a lot of cars through stupidity. We got messed around by a bunch of amateurs that were jealous and didn’t know a damned thing about the problems at Le Mans.

Beating Enzo again, Le Mans 1967.

Getty Images

What were the biggest problems you faced at Le Mans?

CS: The biggest problem was brakes because we were forced to use the 427 engine, which was unnecessary. We could have used a 5-litre engine and had a much lighter car and still got the job done. We weighed 2700lb on the starting line. Our kinetic energy was enormous and we would never have won except that Phil Remington figured out how to change the brake discs and callipers in 20 seconds! And that won the race for us. We had a wonderful engine that would run 10 Le Mans, a gearbox that would run 10 Le Mans, but the reason we won Le Mans was because Ferrari couldn’t change their brakes and we could. We could use the brakes as hard as we wanted and change them three times during the race while we were refuelling. That’s probably never been printed before, but that’s what won the race for us in 1966 and ’67.

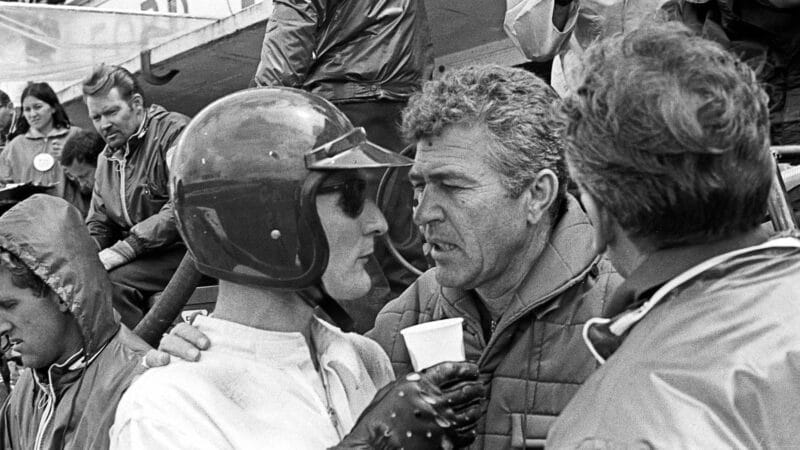

Shelby in 1966 with a proper endurance driver – Ken Miles.

Getty Images

After winning in 1966, Ford had nothing to prove but still came back in ’67. What motivated that decision?

CS: Henry! He just wanted to back it up. In ’65 we laid the plans to race in ’66 and ’67. If we hadn’t won in ’66 we had the groundwork for ’67. The people that caused it to happen were Henry Ford, a fellow named Bill Innis, Leo Beebe and Homer Perry, and all the people at Shelby America. They were the key players.

J-Car set the pace at 1966’s Le Mans test

DPPI

You had two or three different teams running cars at Le Mans. Why?

CS: At Ford some of those silly amateurs decided that it would be best if Holman Moody raced against us. It was stupid because although John Holman and his crew were experts in stock car racing, they didn’t know a damn thing about Le Mans. The best thing that came out of Holman Moody was Dick Hutcherson. He was a stock car racer and he turned out to be as good a driver at Le Mans as any of those guys who had been there and knew the place. This guy was at GM, but he knew what he was doing and the rest of them were worthless. There wasn’t one person in the organisation outside of him that wasn’t a detriment to the programme. I don’t say that because I disliked John Holman – he was a friend. I say it for the reason that it’s the truth about how it really was. They didn’t know what to do. Homer Perry had to carry them on his back and organise the whole thing.

What role did the Ford J-Car play in the Le Mans programme?

CS: A disaster! It killed Ken Miles and it took Roy Lund and Kar-Kraft out of the programme.

Shelby at La Sarthe in 1965, but none of the Shelby American Cobra Coupés finished; AC Cars’ entry came eighth

Getty Images

Did the J-Car influence the Mk IV design?

CS: Yeah. The ’67 car had a different low-drag sleeker-body configuration. It was done mostly by computer. That was the beginning of the computer age and like the Ford 427 Cobra it was the first chassis ever built completely on a computer! Klaus Arning, a German who worked at Ford, did it. No anti-squat, no anti-dive. It was the first chassis ever completely done on a computer. We checked it out by going to Riverside, putting tufts on it and seeing what happened. I think about three versions were made.

Why the name Cobra?

CS: I just thought it up. I didn’t know where it came from. So I said I dreamed it one night, but I didn’t. It just seemed like a good name.

Was your experience at Le Mans a help when you decided on the programme?

CS: I was able to act as a guide. I’d been there a few times; I knew what the problems were.

The Stetson was your trademark. How did that come about?

CS: I had a chicken farm and there was a race in Fort Worth, Texas. I had about an hour to get to the track. I had my overalls on so I jumped into the car, drove over there and won the race. I used to wear an old straw cowboy hat I had at the time. I got a lot of publicity out of my overalls and hat for winning the race. So I thought this is a good way to get publicity and that’s where all this crap came from!

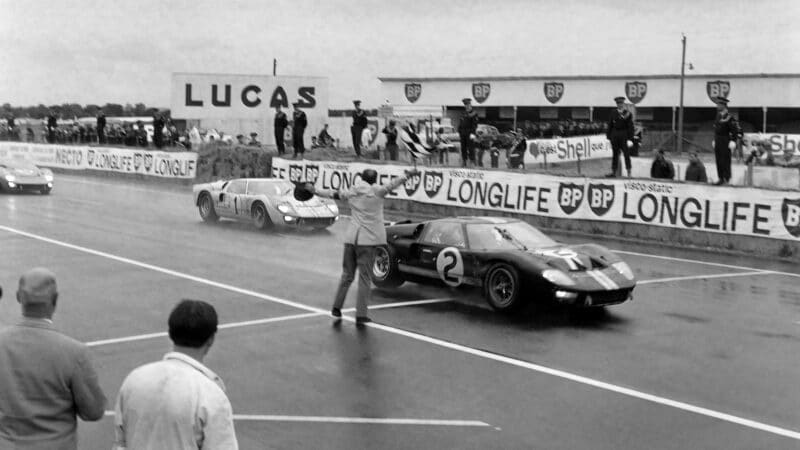

Mission accomplished for Ford and Shelby – a GT40 1-2-3 at Le Mans in 1966 and a racing career high for Carroll

Getty Images

What advice would you give GM, which is undertaking a very expensive long-term programme for the 24 Hours race? [GM was heading to Le Mans in 2000 with its Cadillac Northstar LMP programme]

CS: Get their own internal people out of it and hire Joest or some of the teams that have been at Le Mans like the people that run Toyota or Audi. GM should get out of it completely and hire somebody to build the kind of car they want to build, not a car designed by an engineer in an ivory tower using something that won two years earlier as inspiration. Their first year, they’ll say, “Oh what have we got ourselves into?” and hire somebody who knows how to go over there and compete. That’s what any big company does.

“To put that GT40 programme together is the proudest moment of my racing career”

You have to have people who spend 24 hours a day seven days a week doing it. That’s why the guys who work there like Chip Ganassi make a success of it. They spend seven days a week on one race not like somebody who rolls up on Friday just for the weekend and doesn’t know what’s going on. It doesn’t work like that any more and GM will find that out.

What’s your best memory from Le Mans?

CS: My greatest memory is when we built the GT40s, and we won the race after I’d won it as a driver. Very few have done that, and to put that programme together and get it to work, that’s the proudest moment of my racing career; the greatest thrill I got out of racing!

And your worst moment at Le Mans?

CS: My first year stupidly going off straight into the sandbank at Mulsanne in the wet. I hadn’t enough sense to know that Le Mans isn’t a race. Le Mans is a game of chess!”