The dedicated gang keeping the 500cc flame burning

They fostered some of the great drivers of the post-war era, and now a dedicated group keeps their small flames alive. Gordon Cruickshank went for a 500cc reunion

Jayson Fong

1. 1953 Staride-NortonNotable by its up-front cockpit, Xavier Kingsland’s Staride unusually boasts a central fuel tank. After finding the much-modified car in the US he returned it to original spec, including its swing-axle rear suspension and original Manx. Prices of 500s are fairly static, he says, and he’s pleased about that because it “keeps them affordable for newcomers” |

2. 1947 WaspThough his father Cliff had raced it after buying it from Duncan Rabagliati, Edwin Jowsey’s Wasp sat unused for years while he and Cliff raced other things before an invitation to the 2019 Revival sparked a rebuild. The oldest 500 still racing and famous in period, it dates at least to 1947 with the Fry family, though now in ’52 spec with a Manx replica motor. |

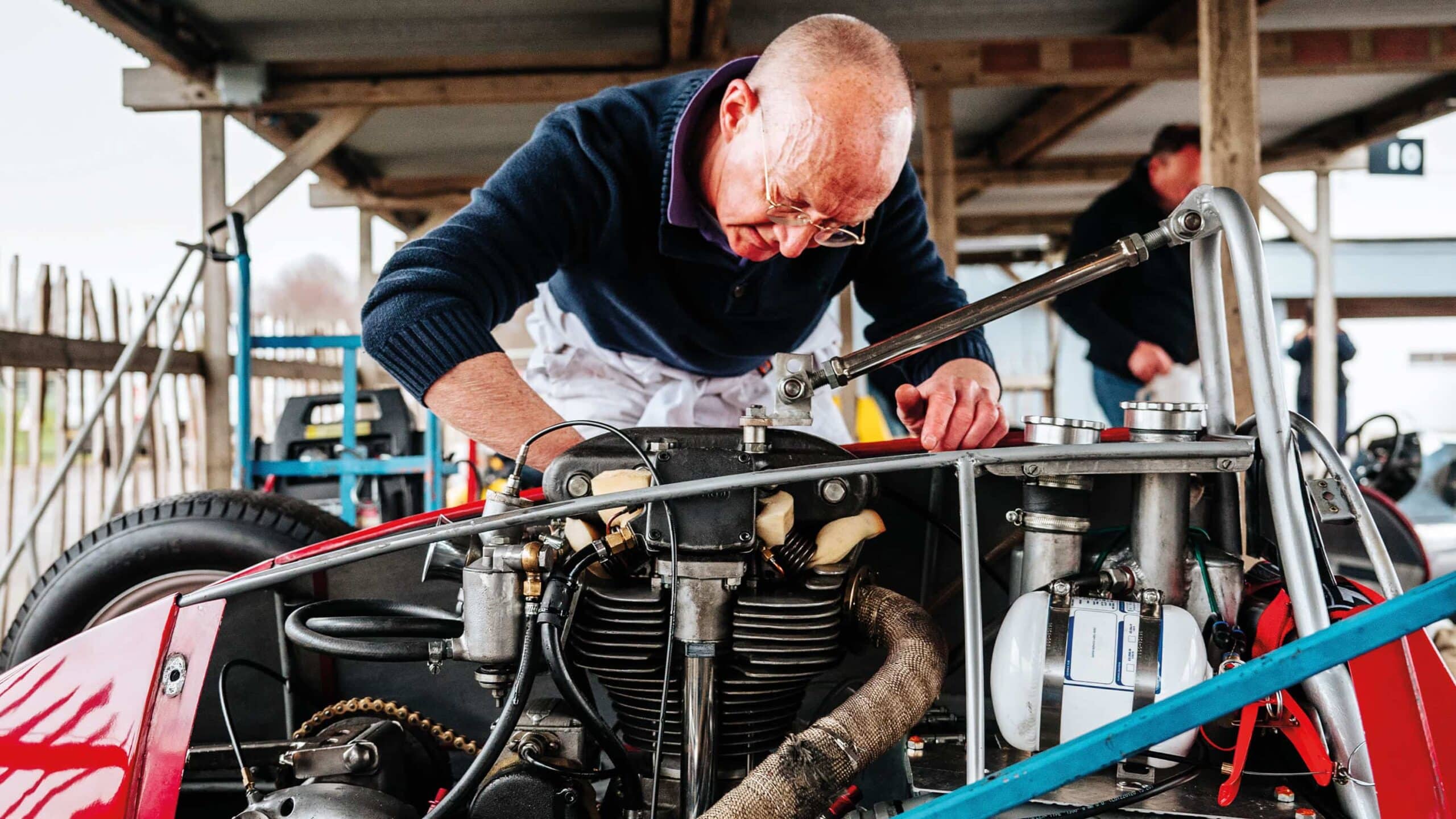

3. 1956 Cooper Mk XNow the 500 Club registrar, Simon Dedman rebuilt the unique Waye to be used for hillclimbs, then looked for a track racer. He found the Cooper sitting unused since 1960, complete and in original form, even through to the engine, although he races with a replica unit. He does his own maintenance and says he’s lucky his wife Jayne is prepared to be his support crew. |

4. 1954 Kieft-NortonBefore buying his car Andy Raynor had done no racing but was drawn to the innovative engineering. He bought it from Charlie Banyard-Smith, who found it in South Africa and restored it, and also makes replica Manx units. Andy has a Norton rep in the car, which retains swing-axle rear suspension. Andy also has a Cooper for hillclimbs and is assembling his one-off Jason. |

5. 1951 Cooper Mk VInspired by seeing 500s in VSCC racing, Mike Fowler bought his Cooper more than 20 years ago, restoring it himself. It’s the last Cooper model to utilise the Topolino layout and box-section chassis. He is another who has a genuine Manx but races a replica unit. Mike looks after it himself, in-between building up a 500cc Bond and trying to fit in racing his FJ Gemini. |

6. 1951 Smith-BucklerRichard de la Roche stands beside one of three machines assembled by racer Ken Smith, of which two survive. Built around a Buckler chassis with Topolino suspension and leaf springs at both ends, Richard’s has the lighter JAP power unit at its heart. He also races a Cooper but enjoys driving the Smith. “I never get out of it without a daft grin on my face,” he says. |

Ancient truisms ain’t always true. There is a substitute for cubic inches. It’s ingenuity, innovation and clean-sheet thinking, and it’s what in the 1950s propelled a class of pint-sized, cut-price oddities from club racing to the front of the grand prix grid. They were the 500s – half-litre bike-engined creations with their motive power out back against all the norms of the age. Born of post-war shortages and tight budgets but propelled by the pent-up frustrations of the war years, they brought forward a new generation not only of drivers, but of engineers and problem solvers. They changed everything.

And they thrived at Goodwood. On the pre-chicane Goodwood too, then an even swifter circuit than today, barring seven decades of vehicle and tyre progress. It sounds counterintuitive for tiny devices with economy powerpacks, but the sheer speed of the Sussex venue only highlighted fractional differences not just in bhp but in overall weight and cornering speeds. If you leave that apex one or two mph faster than your challenger you hit the straight with a couple of feet in hand and that will matter as you approach the next corner.

“There’s some seriously quick people. It’s wonderful to see them going sideways”

Half-litre racing was the perfect arena for tuners, builders and drivers, and these tiny tearaways are still providing the same wheel-to-wheel challenge they always did. So does Goodwood, the only historic historic racing circuit there is. As you’ll hear, it was watching these cars at the Revival that inspired many competitors to get involved. That’s why we’ve grouped half a dozen 500s at the Sussex track and asked their owners why they still offer such brilliant racing.

Andy Raynor, who had done no racing before he was intrigued by 500s tackling Prescott in 2015, sums up what’s great about the class for him: “It’s the perfect entry point – manageable costs, beautiful cars that look, feel, sound and smell fantastic, and there’s always someone around your level in the pack. There are some seriously quick people and it’s wonderful to be passed by them and watch them going sideways round Gerards.”

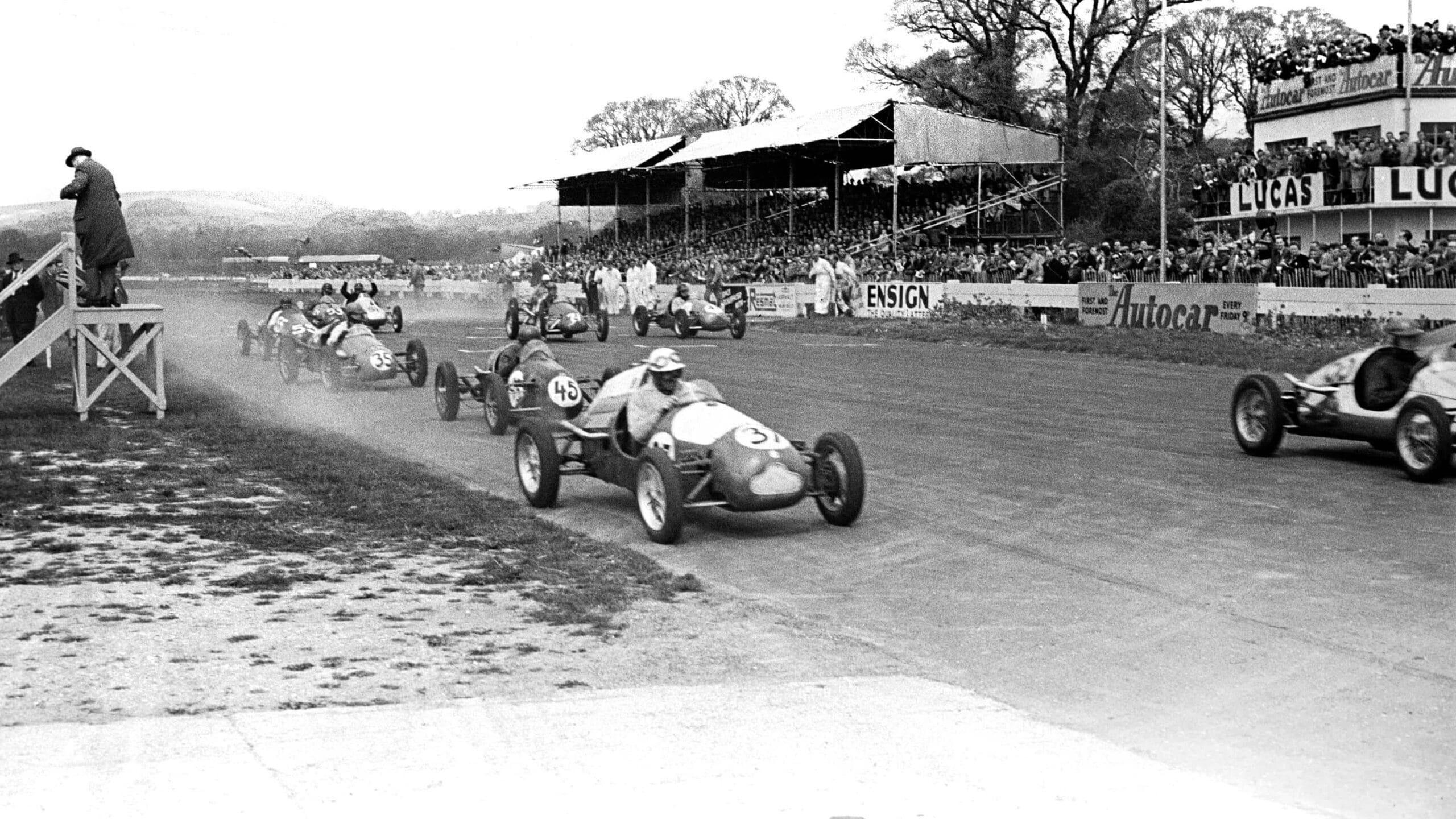

Harry Schell gets his Cooper off the line at Goodwood in 1951. He would be the first to qualify a rear-engined Cooper (fitted with a 1000cc twin) for a grand prix, at Monaco in 1950

Getty Images

Another thing these guys agree on is the range of racing that’s available even for these pint-size machines. Their parent organisation is the 500 Owners Association which runs its own series, but the cars are welcome at plenty of other places. “There are six or seven 500 races usually with a European round,” says Andy. “I’ve been to Angoulême and Zandvoort; you can do front-engined FJ and historic 750 events – there’s probably 15 races you could do, with hillclimbs, sprints and invitation events on top.” Mike Fowler says that racing his Mk V Cooper has got him to places he probably never would’ve visited.

One thing that makes the class popular with organisers is the reliability, due to high preparation standards. Xavier Kingsland reckons much thought and effort goes into preparation “which means fewer DNFs, which makes us more attractive to race organisers”. Andy Raynor says he has raced two replica motors for six seasons and the most he’s done is one main-bearing change.

“I race it with a replica Manx – crankcases are too important to lose!”

“The 500s don’t disgrace themselves with the FJs,” adds Richard de la Roche, who was grabbed by the formula after seeing them here at the Revival. “And it’s the cheapest club to join – £50!”

Almost everyone here stresses the affordability of the movement, which chimes with its origins just after WWII as racing staggered to its feet in the face of rationing and materials shortages. In 1946 impecunious enthusiasts formed the 500 Club, with a national formula that allowed plenty of experimentation. In fact at the first post-war British race, Gransden Lodge in July 1947, the new 500s were the only modern class in a field of pre-war machinery. Eric Brandon’s victory in a Cooper set a theme, and by 1950 500cc had become FIA Formula 3.

We’re used to the little critters now but it was Goodwood that in 1998 propelled them from quiet historic and clubbie events onto the main stage with a 500 race at the first Revival. Since that event more and more 500s are being dragged from obscurity or reassembled, energised by whip-cracker-in-chief Duncan Rabagliati, kingpin in the FJ and 500 world and lover and historian of odd and forgotten racing kit. It’s Duncan who has assembled today’s crop.

Diminutive in size, but they still pack a punch: the fastest 500cc F3 cars can pull over 130mph by the end of a sprint

Jayson Fong

The formula turned out Coopers aplenty of course, biggest builder in those early 1950s, but also Kiefts, Marwyns, Iota, JBS and scores of other hopefuls. There were plenty of one-off specials too; there are a couple here today.

Club registrar Simon Dedman owns the unique Australian-built Waye as well as a Staride, though today has brought his Cooper Mk X, once property of racer and school founder Jim Russell. “It had been in a static collection since 1960 so it was totally complete, even to the Manx Norton engine. But I race it with a replica Manx – crankcases are too important to lose!”

He’s another who was Good-wooed by seeing the 500s at the Revival. “I’d never even done a track day before,” he remembers.

“The series is well policed, everything in period spec. Only safety kit is not period”

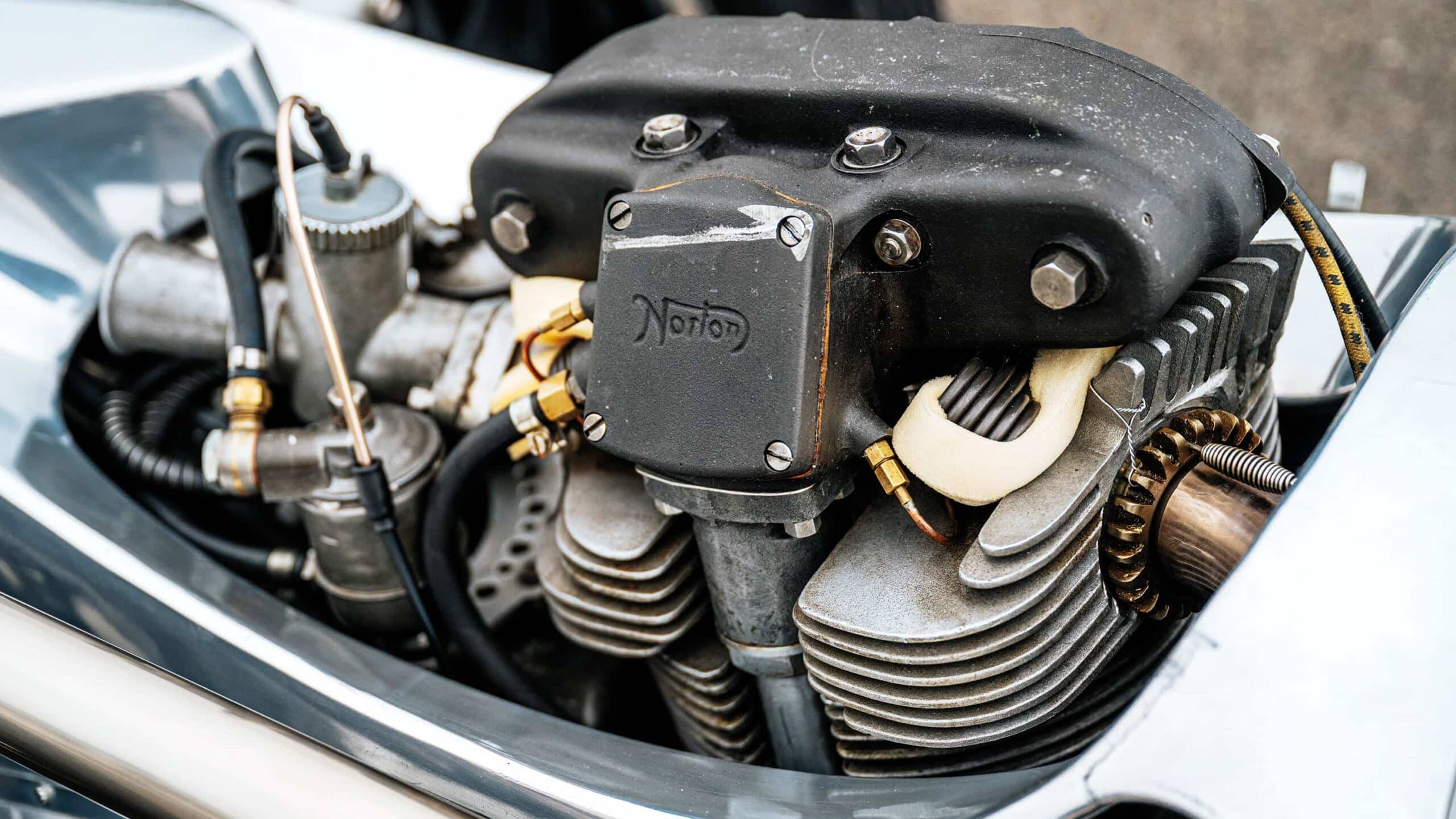

While the club imposes a Dunlop R5 control tyre, engine make is free if in period, though mostly settled into two options – the twin overhead-cam Manx Norton and the pushrod JAP, both air-cooled. The difference isn’t about power but cost and weight: up to 48bhp each, but the JAP weighs two-thirds of the ‘double-knocker’. With original Nortons so precious, several firms make original-spec replicas at around £16,000, although Xavier Kingsland points out “you can buy an original for £4000 and spend £1000 rebuilding it” instead. He feels especially lucky in that he was able to buy the original 1959 engine back to fit in his Staride, one of around 10 built.

Richard de la Roche has brought the only JAP here today, in the back of his exotically named Smith, one of only two. “When I bought it I couldn’t afford to install a Manx. But it’s a brilliant engine; it was only designed to run for four minutes in Speedway, and now it does 20 happily. But it’s total loss oil cooling so we have to put nappies on them!”

Mind you, Richard’s garage also includes a Mk V Cooper-Norton, which he and his son Peter race with success. “His 2019 Goodwood lap was 83mph – not bad for 500cc.”

Hands-down fun: this brave cornering method helps shift the weight, as Xavier Kingsland demonstrates

Jayson Fong

Andy Raynor likes to strike a different note. He’s brought his Kieft, the make which for a time bid fair to rival Cooper, boosted first by Stirling Moss and then Don Parker who took F3 titles with his modified version in 1952 and ’53. Unusually Andy’s car retains its swing-axle rear suspension with pull-cable rubber cord springing, “which is fine if you’re progressive but if you chuck it in at a hairpin you can lose it very quickly. And you’re a long way forward so it’s bloody difficult to get into.”

He also races a JBS and a Cooper and hopes to have something new ready soon – a Jason. “It’s a one-off, which is great because there’s no one to tell you what it should be like; the downside is there’s no one to tell you what it should be like…” It packs a Triumph twin just to leaven the grid mix. “Duncan told me about it – he just wants every car out.”

Duncan will be happy when Mike Fowler finishes his Bond, one of three made. Meanwhile Mike is another Cooper driver: “I just like early ones – this is a Mk V, the last of the Topolino-type chassis before they went to tubes.” That baby pre-war Fiat was a fruitful source for early 500 builders, its transverse leaf-sprung front end a simple, light route to independent suspension, sometimes with another reversed for the rear as on the prototype Cooper. Later Surbiton models abandoned the Italian scheme, but Mike says, “The Mk V is a pleasure to drive, nicely balanced. A good pedaller in a V will live with a Mk IX.” He’s not a bad pedaller himself, with a couple of championships and a hillclimb title behind him.

Thanks to the motorbikes the engines that go with these cars all have a double chain drive, one to the gearbox, the second to the rear axle. “Norton is the ‘box of choice’,” says Simon, “although mine is close-ratio so standing starts are hard and with a dry clutch it can overheat. But it’s good on a big flowing track like this.” Xavier Kingsland, tempted back to racing by the 500s after a 40-year layoff, says that he can do a season rebuild on his 1953 Mk III Staride-Norton for £1000. Once inside it he sits hunched between the front wheels, skimpiest of bare metal panels around him. He runs the car with no engine cover – “I like to see the engineering. And 500s are forever being fiddled with.”

“The series is well policed – no five-speed boxes, everything in period spec,” he continues. “Only the safety kit is not period. Many of us run without belts – with only 48bhp it’s all about carrying speed through corners and that’s aided by your ability to move in the car to change the weight distribution, which is why a lot of us still adopt the old ‘one hand under the chassis’ position, hanging out of the car. You can’t do that with belts.”

“Mine has a small rollbar so you might still get a headache…” Andy chips in.

500cc F3s light up Goodwood in 1998.

Peter Fone

Andy Raynor attends to his Kieft

Jayson Fong

Cooper was the dominant brand in period, and powered a young Stirling Moss

Jayson Fong

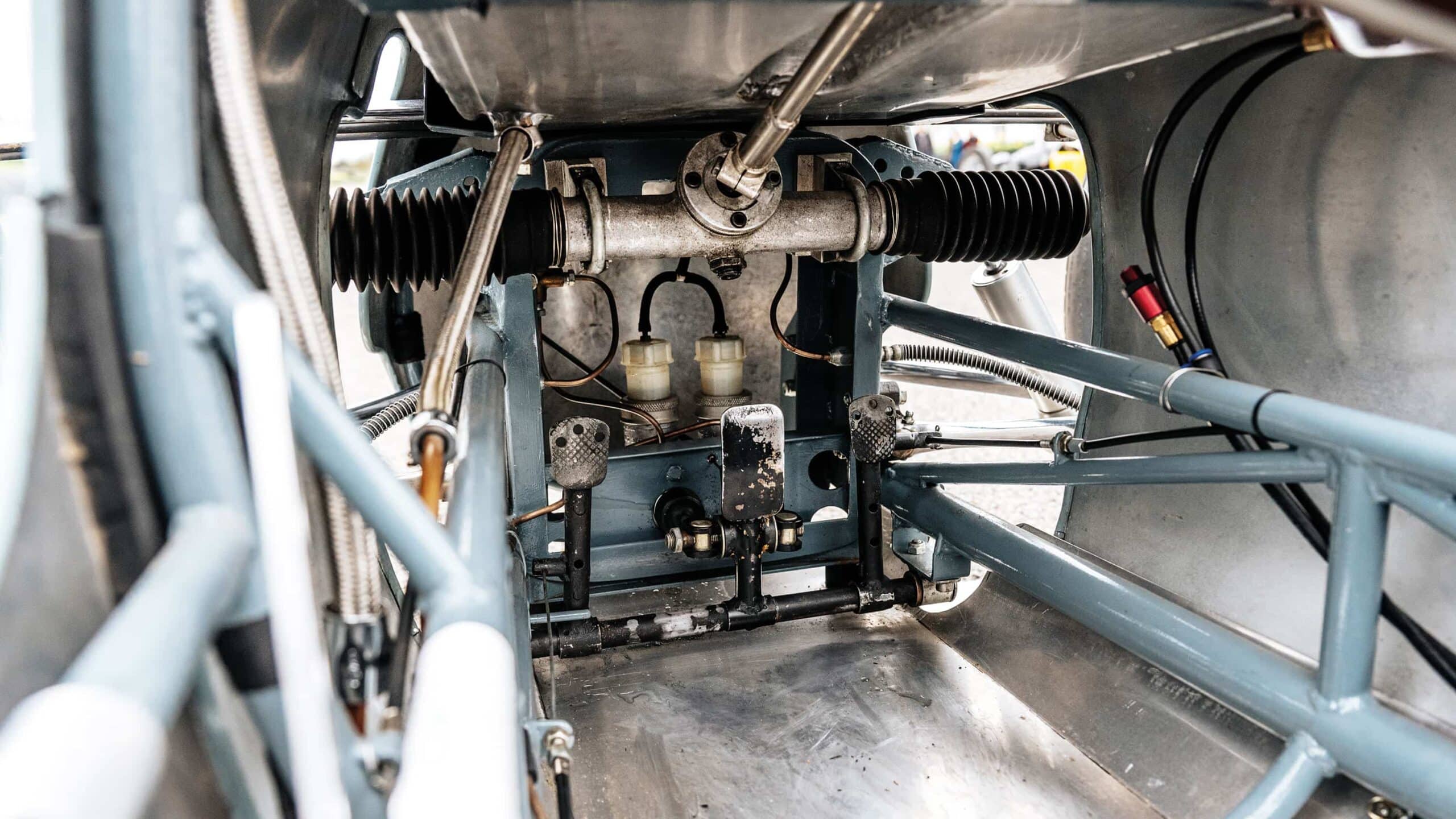

Shot-cord springing for the venerable Wasp’s suspension.

Jayson Fong

A young Moss victorious

Getty Images

The Wasp – in 1952 spec

Jayson Fong

Twin chains are used, one to the gearbox, one to the rear axle

Jayson Fong

Neat rev counter arrangement

Jayson Fong

Vintage 500 action at Brands Hatch in the early 1950s.

Getty Images

Spartan pedal box on Smith-Buckler.

Jayson Fong

Motorbike gearboxes are sequential.

Jayson Fong

Norton DOHC Manx is a favourite, though owners often race new replicas

Jayson Fong

That wacky cornering technique is one of the things crowds love at the Revival – that and the needle-match racing at the front. “I think the skill level required is very underrated,” says Xavier. “I take my hat off to the guys who are doing the best times in sprints – 130mph over the finish line at some.”

Chassis design was open season for the scores of hopefuls who joined the half-litre bandwagon, many built in garages and sheds, so suspensions vary like flowers in the spring. Over the years many of those transverse Topolino leaves have been swapped for wishbones and coil springs while the box-section ladder-type frame gradually became more sophisticated, Cooper leading the way from 1952 with its famous curved tube chassis, flouting ideal structural rules but gaining more and more success as it dominated F3.

“It’s a great club to be in. There’s a great social side and you make good friends”

It didn’t hurt that Stirling Moss switched from Kieft back to Cooper, either. A pivotal moment for Cooper and the movement came in 1950 when Harry Schell qualified a rear-engined T12 1100cc (or possibly just 1000)Cooper for the Monaco Grand Prix, and we know what that eventually led to… And all because if you’re stuck with chain drive it makes sense to bolt it behind the driver.

Thanks to their innate simplicity and common formula, 500s were also being built right across the continents from Estonia to South Africa, but England was especially fruitful, stemming from a rich tradition of pre-war lightweight specials. With their Freikaiserwagen David Fry and Dick Caesar had much success and Joe Fry had even set an FTD at Shelsley in 1947. Edwin Jowsey’s startlingly yellow and black Wasp IV derives from one of the Fry specials and is one of the longest-serving 500s, though it rarely looked the same from one year to the other as next owner Jack Moor made more improvements, notably putting double wishbones on the rear and rubber shot-cord springing, still suspending the car. Through the early ’50s Moor’s Wasp was one of the few specials that could harry the works Coopers and Kiefts.

With prices of cars relatively stable, cheap club membership and some great racing on offer, 500cc F3 is an appealing option for anybody looking to get into historic racing

Jayson Fong

“Jack Moor’s son Nick told us that his dad wouldn’t think twice about completely altering the suspension or any part week on week,” says Edwin. “My father Cliff bought it in 1998 from Duncan for the first Revival but we didn’t start to rebuild it again until 2018 when we got an invitation for the Goodwood Revival. We chose to aim for the 1952 form and when we took the nose fuel tank off surprisingly there was a second nose inside, and the remains of the old suspension that had been cut off.”

Moor had an ‘in’ with Norton but the Wasp arrived with a JAP. “Nick said, ‘That can’t stay!’ So now I have a replica Norton.” So many notable drivers came through that version of F3 – Ken Wharton, Peter Collins, Ivor Bueb, Alan Brown, as well as Bernie Ecclestone. “It was at Goodwood when Ken Tyrrell came over saying he remembered the car well that we realised how well-known and distinctive this little car was,” says Edwin.

Though the cars and motive power vary, one thing that all our group commend is the 500 club spirit. “The club really looks after the enthusiast,” says Andy. “If you have a problem during practice the car will be surrounded by people trying to get you out on the track again.”

Even the AGM is fun, according to Xavier. “We put on a sketch show – members entertaining members. The ladies all dress up, and there’s dancing in the paddock.”

“It’s such a great club to be in.” says Mike Fowler. “There’s a great social side and you make good friends. It’s become my life.”

Not a bad takeaway for the little cars.