John Watson: The Motor Sport Interview

John Watson recalls ruthless team-mates, dealing with downforce in the ’80s and the privilege of working with motor racing titans Roger Penske and Ron Dennis

Hoch Zwei via Getty Images

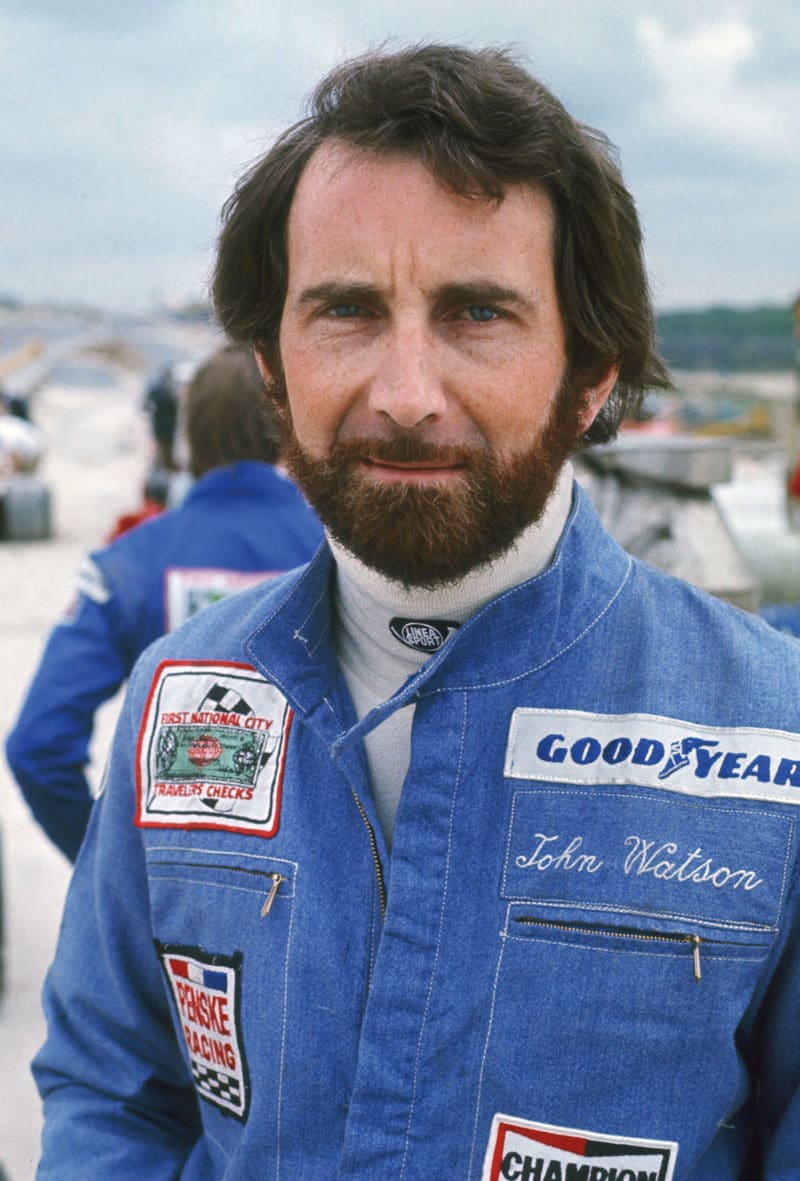

John Watson came to England from Northern Ireland to make his name in 1969. His natural talent was immediately recognised and his journey to grand prix victories had begun. Wattie was 26 when he had his first (non-championship) Formula 1 race, 1972 at Brands Hatch in a Hexagon March 721, impressing with sixth place. His first grand prix, with a Hexagon Brabham, came at Silverstone in ’73 and the following year he scored his first points with sixth in Monaco.

After a troubled season with Surtees in ’75 he was signed by Roger Penske and took the first of his five grand prix victories in Austria. In ’77 he went to Brabham alongside Niki Lauda, moving to McLaren in ’79 where he stayed until ’83. In ’81 he won the British Grand Prix by 40 seconds from fifth on the grid in John Barnard’s all-new carbon fibre McLaren MP4/1. These days he’s a commentator for both F1 TV and for the GT World Challenge on Eurosport.

Motor Sport: Let’s start in the present and get your take on Formula 1 in the modern era. What do you make of the sport today compared to when you were racing?

John Watson: “What we see today, it’s a million miles away. It’s the scale of F1 today – more a huge business than a sport in some ways. It’s an evolution, it’s progress. Some people won’t like it but the new, younger generation are loving it, and that’s in part down to Drive to Survive on Netflix. And, let’s remember, social media wasn’t even invented when I was racing.

“The sport is always evolving. In 30 or 40 years’ time Formula 1 will have embraced yet more new technologies and will be different yet again. Back in the day you had a Cosworth engine, a Hewland gearbox, you built your chassis and went racing, then along came wings, ground effects, aerodynamics and then with the coming of carbon fibre composites the cars became so much safer.

Penske Racing overalls in the mid-1970s, towards the end of the beard era

Getty Images

“When I crashed the McLaren at Monza in 1981 the impact split the car in half but I was left sitting in the carbon tub unscathed, and safety has improved still further since then. The world has changed, life has changed, and Formula 1 reflects the speed at which these changes are happening.

“As a journalist you know how easy it used to be to talk to a driver, or a team owner. Now I believe you have to go through a myriad of channels just to ask a few questions. That’s just one small example of how big, and how corporate, the sport has become. It’s less personal, maybe not as much fun as it was for us in the ’70s, but then you could say the drivers of the ’50s probably had more fun than we did, so we’re back to the sport evolving all the time. I’m certainly not critical of F1 today, but yes, it’s very different from when I was a grand prix driver in the 1970s and ’80s. I reckon the budgets for paddock ‘brand centres’, or whatever they’re called, are probably bigger than the racing budgets for any of the teams I drove for. That’s evolution, like it or not, and Formula 1 looks to be in a good place these days.”

You raced with some of the greats of your era. How did it compare being team-mates with Niki Lauda and Alain Prost, multiple world champions but different characters?

JW: “At Brabham in 1977 Bernie Ecclestone asked me what did I think about Niki joining the team for ’78. I said I had no problems with that as long as we had equal status, and equal treatment. What I had not appreciated was what a very good operator Niki was – a clever man aside from all his qualities as a driver, and Bernie liked a good operator.

“I liked Niki but he didn’t give a damn about me professionally“

“He brought his own personal sponsor, Parmalat, and they became the team sponsor, so that gave Niki a degree of leverage and he was able to swing the lead in his favour. I liked Niki personally but he didn’t give a damn about me professionally. In effect he became number one and didn’t want me to be a problem in his quest to win a third championship, with Brabham. On reflection the only way I could have won that battle within the team was to have gone out and dominated the championship by not only beating Niki but also by beating Lotus and everyone else. He was a very impressive competitor in whatever area you choose to look at.”

And Prost at McLaren in 1980? You were already there when he joined and I’m guessing he was a completely different kind of team-mate?

JW: “I’d joined in ’79 – a difficult year with the M28 and then the M29, which was very similar to the Williams, but copying is one thing, understanding is another. Frank Williams had employed Patrick Head who was a clever engineer and he understood aerodynamics. So after a year with two difficult cars, Alain joined the team in 1980. Marlboro wanted a new generation of driver, and they brought Alain and Kevin Cogan to a test at Paul Ricard at the end of ’79. It was immediately clear that Alain was a complete natural in a Formula 1 car.

The minute he drove out of the pitlane I said to the team, ‘There’s your guy.’ It was just the way he got into gear, picked up the throttle, rolled down the pitroad, you just can tell. He had a sensitivity for driving a car.

“From the first race Alain was extremely impressive – one of his gifts was being able to work with the equipment we’d been given. I knew the fundamental problem was with the aerodynamics but he worked with the team, playing around with rollbars, springs and dampers, and was making small gains. At mid-season we had a better understanding of the aero, the car became more competitive and, at that time, there were serious moves afoot to bring in Ron Dennis and John Barnard to take McLaren from being a 1970s team to an ’80s team.

“Alain got a carbon fibre underbody for the British Grand Prix; I didn’t get mine until the Dutch when the M30 was introduced and given to Alain. He struggled with the new car while I was finding I could get more out of the M29 once I had the new underbody. In Canada and America Barnard worked with me on my car and I remember him telling the mechanics to lift the ride height significantly.

“He realised that not enough air was getting under the front of the car to make the ground-effect tunnels work effectively. The car was transformed. So, while McLaren had seen Alain as the salvation of the team, the answer was all in the engineering, and by the end of the season he’d decided to go to Renault. Alain was never an operator like Niki. He just got on with the job, but of course he needed to be one later in his life with Senna at McLaren.”

Brabham bigwigs at the Swedish GP in 1978, from left: Gordon Murray, Bernie Ecclestone, Watson and Niki Lauda. The team arrived at Anderstorp with a trick up its sleeve – the fan car

Hoch Zwei/Getty Images

Alain Prost, right, joined John Watson at McLaren in 1980 and quickly found form, with a sixth and a fifth in his first two Formula 1 races

GP Library/Getty Images

By 1977, Wattie was with Brabham, driving the Martini- liveried BT45

Hoch Zwei/Getty Images

While we’re on the subject of drivers, you have sometimes been reserved, shall we say, in your assessment of Mario Andretti’s F1 championship in 1978.

JW: “Let’s be clear, he’s one of the most versatile drivers in the history of the sport. His record is phenomenal in so many different categories and I would never want to demean his achievements. Mario had done all the hard yards for Lotus in ’76 and ’77, helping the team get back to being competitive. Then in ’78, with the Lotus 79, he was given the status of number one driver when, in terms of sheer speed, I think most people would say his team-mate Ronnie [Peterson] was the quicker driver.

“Speed, however, is not everything when it comes to winning a championship. Mario had an extremely good relationship with Colin Chapman, both on a technical and personal level, and he was a good communicator. So Mario was in the number one seat and Chapman knew that by winning a world championship with an American driver, a market for Lotus road cars would open up in America for him. So there was a commercial gain for Chapman and Lotus with Mario winning the title rather than Ronnie who was, if you like, the hot-rod driver, the quicker of the two.”

At times the 1981 Dutch Grand Prix resembled a stock-car race. Watson is in the McLaren (No7) leading Mario Andretti’s damaged Alfa Romeo

Grand Prix Photo

For a great many fans, Gilles Villeneuve is an absolute hero, a swashbuckling character who was never far from the headlines. I think you saw him differently from the cockpit?

JW: “Look, first I want to say that Gilles was a hugely gifted and talented racing driver – that’s what he was but in many cases he drove beyond the maximum, beyond the limits of the car. The wheel-banging with René Arnoux at Dijon, I didn’t think that was clever, and then he spun at the Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort and dragged the car round with its backside on the ground.

“I was critical of incidents like that but then he also drove some outstanding races, like Monaco and Jarama in 1981, in a car that was a dog. He had those virtuoso performances when the Ferrari wasn’t a great car. In those days there were tyres from Michelin and Goodyear and sometimes, especially in the wet, the tyres could make a huge difference depending on what you were running.

“When people eulogise a particular performance they may not always know the reasons why one driver appears to be so much better than another. I always thought the risks you take are the risks you have some control over, not the ones over which you have no control. Risk management is an important element in racing and nobody is bulletproof. So I simply respect drivers like Stewart, Lauda, Fittipaldi or Prost who didn’t take risks they could not control.

“Ferrari, at that time, was the wrong culture for a driver like Gilles. If he’d gone to a British team I think the management would have helped him be a better driver, not a faster driver, but a more complete driver who understood the limits of what he could do, and where. I do realise, however, that Gilles is a legendary figure for many fans.”

Gilles in Spain, ’79 – Ferrari was the wrong fit for the Canadian

DPPI

From drivers to team bosses now. You raced for Roger Penske, Bernie Ecclestone and Ron Dennis. Three titans of the sport, and three very different people.

JW: “Bernie was not a hands-on manager. He was a businessman who bought a Formula 1 team and had very clear views about the presentation and how the team should be run. For a long time there was virtually no sponsorship but he couldn’t continue like that. He gave people like Gordon Murray and Herbie Blash great autonomy within the team, to manage and run it while he did the nuts and bolts of the finances.

“Bernie was a gambler. He liked rolling the dice, challenging the odds, and that was how he operated. He’s a very powerful person, exceptionally clever, on a different level from other team principals of that era. He was always looking at the future, where Formula 1 might go and the role he would play.

“Even now I don’t think much goes on in Formula 1 that Bernie doesn’t know about.”

“A great example is when he ran the Brabham fan car in Sweden. It was like a bomb had gone off in the paddock, and he took a totally pragmatic view. He said, ‘We’ve got what we’ve got, let me race it, and I give you my word we’ll never race it again.’ That’s how he resolved the problem with the other team owners. The car was never banned. Gordon Murray swears it was a perfectly legal interpretation of the rules to this day, but it caused an absolute furore. Ken Tyrrell was furious, frothing at the mouth; Colin Chapman was doing his nut as he realised the fan car could defeat his ground-effect Lotus for the rest of the season.

“Bernie very quickly saw that if he had persisted with the car it would have endangered the formation of FOCA [Formula One Constructors’ Association]. There was a far bigger game in town, and he was already well into that game, whereby he would become the pre-eminent team principal who would represent all the other team principals. He already had his eye on television rights. It was a seminal moment in his career when he realised he’d have to give in on the fan car to win something more valuable further down the road. Even now I don’t think much goes on in Formula 1 that Bernie doesn’t know about.”

Victory at the British GP in 1981 for McLaren

GP Library/Getty Images

On the podium with Gilles Villeneuve at Jarama, ’81

DPPI

Roger Penske… still quick

Alamy

And Roger Penske? Another extraordinary man who has achieved so much and continues to work into his eighties.

JW: “Yes, he never had the desire to rule Formula 1, but his success in North America has put him in an extremely influential position. Back in the ’70s, when I raced for him, he already had a number of very successful teams in America and then he accepted the challenge of Formula 1.

“He uses his teams as a platform to grow and develop his many other commercial interests. Racing is just one part of his empire which includes dealerships and car and truck leasing right around the world. Through his many sponsorships he makes contacts with the decision-makers in some of the biggest global companies and car manufacturers.

“In ’76 the presentation of the Penske Formula 1 team was groundbreaking for such a small team based in Poole, Dorset and employing so few people. Roger is a remarkable man, totally self-made, and to see him drive that Porsche at the Goodwood Festival of Speed last year was incredible.

I was behind him at the start in the Penske PC4 and, I tell you, he was not hanging about, but then he was a very successful driver before he became a team owner.”

Watson was ever-present for Penske in the 1976 F1 season – here at the Spanish GP in the PC3. His highest position in this car was fifth in South Africa

GP Library/Getty Images

Now to Ron Dennis and your McLaren International years, which included winning the British Grand Prix in 1981. Quite a complex character, Ron, I think…

JW: “Ron worked his way up from being a mechanic at Cooper which in itself is extraordinary. I first met him when he was running the Rondel F2 team with Neil Trundle and what impressed me was the level of presentation of every element of the team. He had a vision, he had a clear idea of what he wanted McLaren to be and it was beyond anything that anybody else had previously done. He’s a perfectionist and he worked extremely hard to realise that vision.

“Ron is a lateral thinker, like Bernie, and in ’81 he called me to tell me to get to a hotel in Weybridge. He said, ‘Don’t ask why, just get there.’ I went into this seminar, full of captains of industry. It was presented by Edward de Bono who preached the skills of lateral thinking. He told us not to look at a problem in a linear way, but to look at it from all different angles and come to a judgement that way. Ron was there to improve his ability to run his business more competitively and to make me start looking at myself.

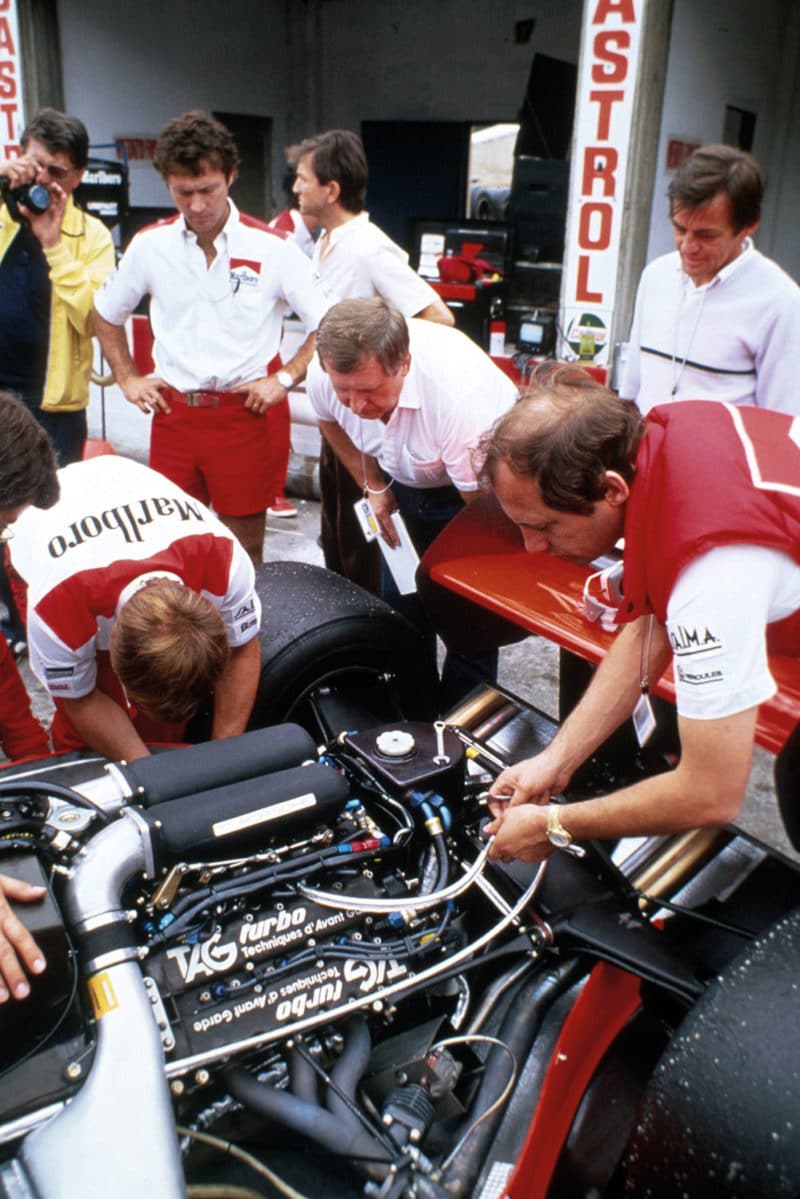

“At the time I wasn’t bright enough to pick up the message. If I had been… maybe my racing life would have been easier. Ron was never satisfied. He was always pursuing more and more, like bringing Niki [Lauda] into the team and getting the turbo engine from Porsche. He wanted engine exclusivity, commissioned Porsche to build that engine, and then he told them there would be no Porsche badges, that this was a TAG engine, his engine. He was very firm with them. It wasn’t the most powerful engine but it was very driveable, very fuel-efficient and reliable.

“Ron was extremely keen on reliability across the board. He hated hearing ‘bad luck’ stories when something on the car failed. He wouldn’t countenance bad luck. It was bad engineering, he said, or bad manufacturing, bad design, bad driving or bad management. He virtually eliminated unreliability.

The Porsche-built TAG V6 turbo arrived towards the end of 1983, giving Ron Dennis, right, the reliability he craved

Hoch Zwei via Getty Images

“In the Honda days, before the race, each car had a brand new engine, brand new gearbox, brand new suspension, because he knew that would reduce the likelihood of a failure. His success led to more success, like it was perpetual motion. The more he won the bigger the budgets, the bigger the sponsorship, and this dragged other teams along to where we are today. He was ahead of his time. After the heady days of the ’80s and ’90s he wasn’t able to sustain that level of success. Maybe it was his other commercial ventures, like his road cars, building the McLaren Technology Centre with Sir Norman Foster and even highly sophisticated hi-fi systems that was partly the cause. Overall, what the man achieved is mind-blowing, his obsessive attention to detail, his work ethic. The sport, I think, is the better for people like him.”

This year we have ground effects again in Formula 1. You raced the previous ground-effect cars so can you compare how it was back then, and how it is today?

JW: “Well, we’d never experienced the kind of loads put on the car by the advent of ground effects and the downforce it created, starting with sliding skirts in the ’70s and increasing from there. How you deal with big changes like that depends a bit on what you’ve been used to driving.

“In 1982 we had so much downforce we ran without a front wing“

“When Tommy Byrne did a test in the McLaren MP4/1 in 1982 he’d won the Formula 3 championship and driven a Theodore but never anything like the McLaren. He jumped in, went out and did some very quick times. He had no preconceptions or comparisons to make with a car at that level. We did have porpoising in those days but, like today, the engineers soon found a way round it. The difference is that we had full length sidepods with a venturi within that sidepod whereas now the cars have much shorter sidepods so as to get the centre of pressure further towards the back of the car.

“In 1982 we had so much downforce we ended up running without a front wing, balancing the car with a degree of attitude or by adjusting the rear wing and the thickness of the skirts. So it was a different way of generating downforce with ground effects. I’ve seen some violent porpoising this year and that’s unpleasant. The car gets into a pitching motion, and that’s in the corners as well as in a straight line. It’s no fun when you’re in the braking zone, entering a corner, and the car is a bucking bronco. With new developments it takes time to work through the process of understanding how to perfect what a new regulation has given you.”

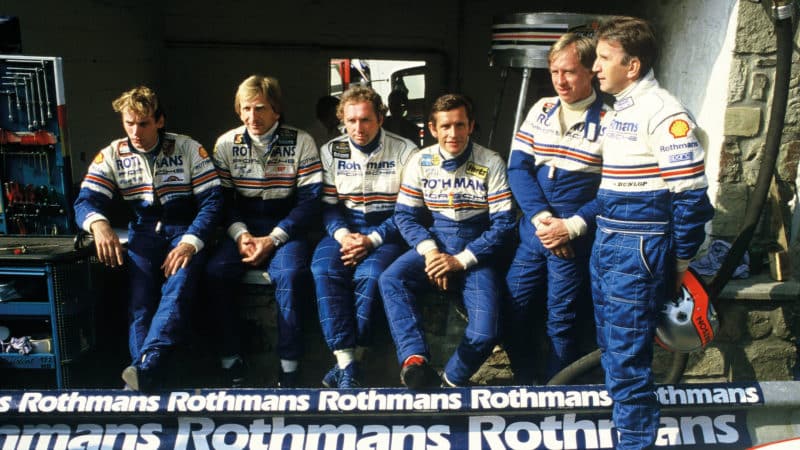

From left: Porsche drivers, 1984 (L-R) Bellof, Bell, Mass, Ickx, Schuppan and Wattie

Porsche

Jaguar win at Jarama with Jan Lammers, 1987

Alamy

Watson was rarely off the podium in the 1987 World Sportscar Championship, driving the XJR-8 to three wins

Jean-Marc Teissedre/DPPI

You left Formula 1 abruptly at the end of ’83, having won five grands prix, and went Group C racing. Why did you stop?

JW: “I didn’t decide to stop. At the end of ’83 I came home from the South African Grand Prix, and on the Monday I got a call from my team-mate Niki who said, ‘Be careful – Prost has lost his drive at Renault and is looking to take your seat.’ Niki didn’t want Prost in the team. He could see that he would be a threat, bigger than me, and so, to cut a long story short, I found myself out of a job at McLaren. There was no negotiation, no discussion. I was told that the team had signed Prost and my services were no longer required.

“I was out of contract at the end of that year anyway and I had two offers to drive in ’84, one from Peter Warr at Team Lotus whose sponsor John Player wanted a British driver. I turned it down because I knew Lotus didn’t want me specifically – it was that team manager Peter Warr, for whatever reason, didn’t want Nigel Mansell in the car for another year. I’d had 10 years in Formula 1, the chemistry with Lotus didn’t feel right, so I thought, ‘OK, I’m moving on.’

“Going cold turkey from grand prix racing leaves a huge gap in your life. I didn’t want to stop racing, but Lotus didn’t appeal, and I already had some links with Porsche, which turned out well when Stefan Bellof and I won the Fuji 1000Kms in a Rothmans Porsche 956 in 1984. Stefan was a remarkable young guy. He was way quicker than anybody in that 956. In the right place at the right time he would have been Germany’s first Formula 1 world champion but tragically that wasn’t to happen. A great loss to the sport.

“I got the opportunity to race for BMW in the GTP series in America. I wanted to do that, but the programme got binned. Then in ’87 I joined TWR Silk Cut Jaguar in Group C, a fantastic car, full carbon fibre chassis, proper aero, a powerful V12. Jan Lammers and I won three races and finished runner-up in the Sportscar Championship.”

And later there was a move to television…

JW:“In the ’90s I was coming up to 44 years old. Not many good teams wanted someone of that age, so I began doing commentary, got involved with the Silverstone Driving Centre, and now I had a new direction. The Formula 1 commentary keeps me in touch and I enjoy using my experience to help the audience enjoy a grand prix.

John Watson, the TV commentator

Alexandre Guillaumot/DPPI

Then there’s Stéphane Ratel’s GT World Challenge. It’s stunning racing and very competitive due to its balance of performance formula which ensures that no single manufacturer will be dominant over a whole season.

“It’s affordable. You can buy these GT3 cars from Porsche, Mercedes, Ferrari, McLaren, whatever, and race. It’s given young drivers a professional alternative to F1, where there is no place for a driver without a big budget. Stéphane is another good operator and he’s putting on quality racing which has attracted big brands and good drivers. People want to be entertained, with close racing, at whatever level that may be.”