Marcel Pourtout: Carrossier, book review

Fresh details about Gordon Cruickshank’s favourite coachbuilder Pourtout are hard to unearth – making this book a real treasure

Paulin’s pen strokes are evident in the sleek mid-1930s Darl’mat Peugeots

DPPI

I’m glad I can open this review with the Darl’mat versions of the Peugeots which raced successfully at Le Mans and elsewhere in the 1930s, otherwise a book about a French coachbuilder could seem a little peripheral. But Pourtout shaped many a racing car, so my favourite coachbuilder has a valid excuse to be here. Why favourite? In its finest years Pourtout displayed an originality of line which made its products unique and dramatic – the prime example and the one most people know being the Bentley 4¼ built for Greek shipping magnate André Embiricos to a design by Georges Paulin. It too raced at Le Mans, as a private entry, finishing a remarkable sixth in 1949.

Well known for his automotive historical writing, Jon Presnell has had much support for this work from the Pourtout family who still maintain the company archives. Nevertheless, he starts his preface by bemoaning how little information there is, which makes the wealth of detail here quite an achievement – for example much background on the streamlined 4¼ and sketches of further proposed Bentleys I’ve not seen before.

It was a surprise to me that the company, founded in 1925, only closed in 1994, having occupied itself in its last few decades with corporate work, a far cry from its glamorous pre-war clientele. That ability to adapt to circumstances made it a rare survivor from the golden days of bespoke coachwork, unlike such long-vanished contemporaries as Figoni & Falaschi.

Even early Pourtout designs show an essential elegance often emphasised by letterbox windscreens which added a rakish style to a Hispano-Suiza or Delahaye chassis. That trick worked especially well when in 1933 a dentist called Georges Paulin offered Pourtout his clever retracting steel roof design, soon added to Peugeot’s catalogued product line. It was Paulin who brought a unique vision to the company’s work.

“In its finest years Pourtout displayed an originality of line which made its products dramatic”

Meanwhile racers small and large came to the firm’s workshop to be clothed, thanks to a garage owner with a network of racing pals. Presnell has collected a wide range of photos including some lovely shots of these one-offs on Samson and Lorraine chassis which raced widely.

Still, despite some fabulous designs which shone at concours d’elegance the company was struggling until Lancia began building cars in France, which brought Pourtout much work including catalogued Lancia production models. All this was news to me as I hadn’t seen most of these striking machines, often with Paulin’s patent Eclipse retracting roof. And the photos keep coming, including an astonishing Peugeot 601 at another concours, that shop window for coachbuilders, with a flush-sided body that surely belongs to a future decade, and those sleek Delahaye racers that were a privateer favourite in the mid-1930s.

Sleek perhaps, but suddenly outdated when in 1936 Peugeot dealer Émile Darl’mat decided to offer his own range. This was when Paulin, by now the de facto company designer, made the carrossier into fashion leaders, with a streamlined, almost aeroplane-inspired line which no longer owed anything to carriages, especially the plunging tail with heart-shaped registration plate. These too saw the Pourtout name streaking down the Mulsanne straight as well as posing with couture-clad ladies on the concours circuit.

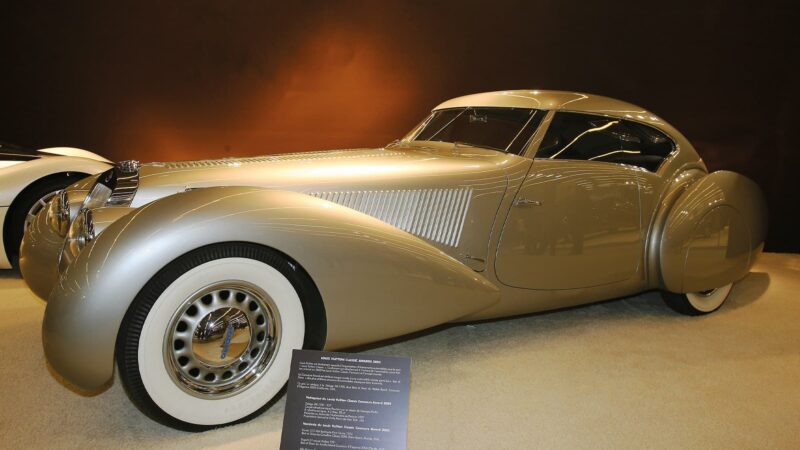

This is when Pourtout and Paulin co-operated in some of the most stunning cars ever seen, such as the Delage D8-120 Aero coupé, a firm fixture in my ever-shifting list of top-10 most beautiful cars. Presnell includes comparisons with streamliners by Andreau and Mercedes which show Paulin wasn’t alone – he just did it better.

This glorious era more or less came to a close with the famous Bentley, not withstanding some racing Rileys and beautiful Talbot coupés, so much more restrained than the flashy Figoni T150s built on similar chassis.

Forgive me for being carried away by aesthetics. Presnell doesn’t neglect the human side, though, describing Marcel Pourtout’s difficult choices during wartime occupation and how he had to defend himself while dealing with the disappearance of the good times and finding new markets – including a small electric car.

The Delage D8-120 coupé was a joint Marcel Pourtout-Georges Paulin piece of theatre

DPPI

As Presnell puts it, “The Germans leave, and the problems begin…” There is a wealth of family detail about founder Marcel Pourtout and his supremely supportive wife Henriette (she’s quoted as having an eye for elegance, implying that she had oversight of the firm’s designs), and their many children, some involved in the company as it transitioned through the 1950s into a new era building expanding caravans, bubble-top bateaux mouches for cruising the Seine and bizarre advertising one-offs which would become the company’s calling card.

By now the racing work had faded away but there’s some impressive creativity to admire – giant mobile hoovers and sticky-tape dispensers are only part of it.

Family tensions are frankly depicted, backed by first-hand memories, letters and financial facts, as losing key contracts and taking on a costly new building finally kibosh the company’s viability. An extensive section of appendices covers chassis numbers, survivors and specific marques, making this a reference work as well as a fascinating look at the finest years of bespoke coachwork. It is the book you would want written on this innovative coachbuilder.

It may be true that the firm’s great years were in the late 1930s, but perhaps, as Presnell says in his conclusion, its finest achievement was simply in adapting and surviving for so long.

|

Marcel Pourtout: Carrossier Jon Pressnell Dalton Watson, £110 ISBN 781854432865 |