The fiery trail blazed by Hesketh Racing: from F3 to F1

Dismissed as cork-popping playboys, it was hard not to like Hesketh’s fun-at-all-cost ethos. Fifty years on from its inception Anthony ‘Bubbles’ Horsley tells Simon Arron about the team’s riotous ride from F3 obscurity to the F1 podium

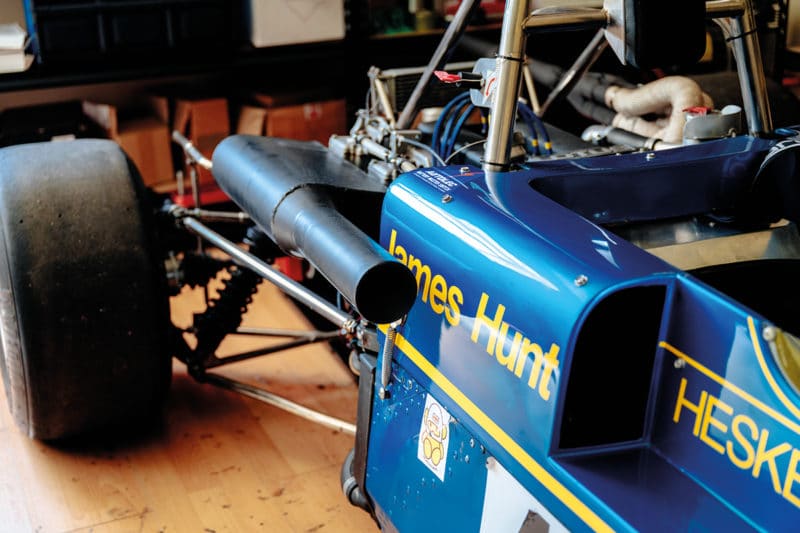

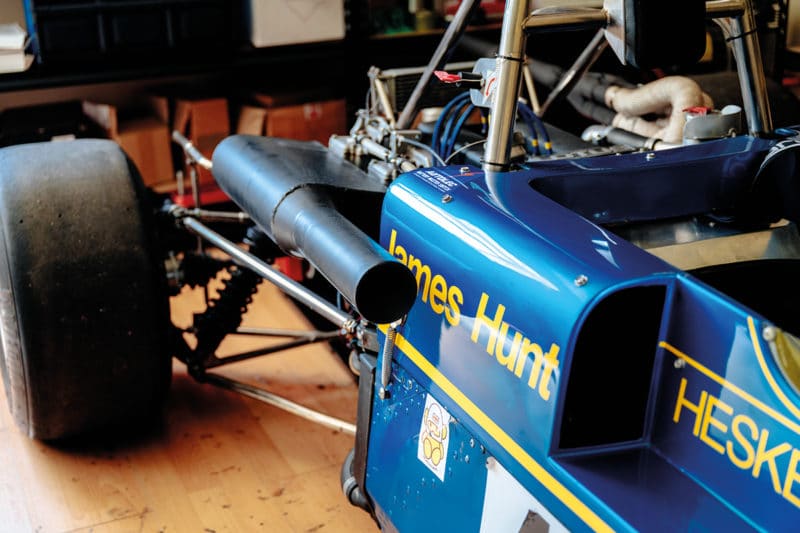

James Hunt’s final Formula 3 races came in a Hesketh Racing Dastle Mark 9 – designed in 1972 by Geoff Rumble

Good grief. I haven’t sat in this since I climbed out at Brands Hatch in 1972, having just buried it in the bank…” Half a century on, ‘Bubbles’ Horsley (it says ‘Anthony’ on his birth certificate, but nobody calls him that) lowers himself into a small but significant slice of motor racing history, one of two Dastle Mark 9 Formula 3 cars that were the founding pillars of Hesketh Racing when it launched 50 years ago.

Hunt failed to make a mark in British F3 in ’72

The highlights of the Hesketh story are well known. In 1973, only the second year of the team’s existence, it emerged as an unlikely front runner in the world championship, running a customer March chassis for James Hunt. It then became a constructor and won one of its earliest Formula 1 races, the 1974 International Trophy at Silverstone, before Hunt scored its lone world championship victory in the following season’s Dutch GP at Zandvoort. The money was running out by then, though, and the factory team folded at the year’s end, though Hesketh continued to sell cars to customers through to 1978 – a humble end to a bright, breezy story that commenced in the unlikeliest of circumstances. And these Dastles herald its genesis.

Worn smooth by the gear changes of Hunt

Today the cars are owned by amateur racer Rob Johnson, boss of Classic & Sports Finance, who campaigns a Triumph TR4 in Equipe GTS events. “I didn’t acquire them because they were particularly good cars,” he says, “but the Hesketh story is one of the most engaging in British racing history and they are an important cog within that, but something not many people know about.”

Suzy Miller, wife of Hunt, in a Hesketh T (currently available in the Motor Sport shop!)

One chassis is a runner that is due to be returned to period specification; the other is complete, but unassembled, and will in time be rebuilt to sit alongside its stablemate. The work will be done by BIOS-sport, an engineering firm run by Peter Sneller, who once manufactured Formula Ford cars under the Zeus banner.

Hunt failed to make a mark in British F3 in ’72

“Why did we choose to run Dastles when there were so many possible alternatives? Good question,” Horsley says. “I’d been driving a Dastle midget racer on short oval tracks so I had a relationship with the company, and in effect we’d be a sort of works team, which appealed.”

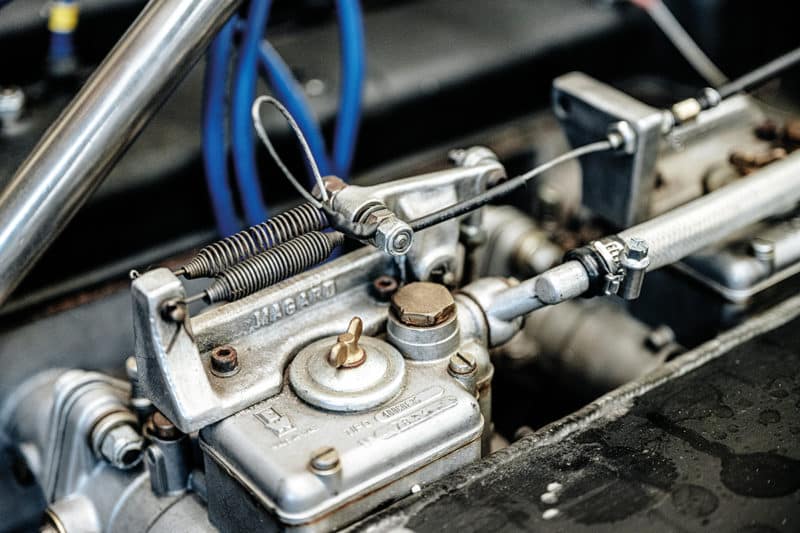

Twin throttle return springs mandatory on competition engines

Horsley had started racing early in the 1960s, at the wheel of an Ettorne, a 500cc F3 racer crafted by George Henrotte. “I’d left school at 18,” he says, “and was desperate to get into motor racing. I’d approached Cooper, Reg Parnell and all these UK-based teams, asking whether they needed a van driver, a gofer or whatever, but had absolutely no luck.

Hand-stitched Racetech wheel

“I ended up working as a waiter at The Mitre hotel near Hampton Court Bridge on the Thames. One day a group of Americans came in and talked about this Formula 1 team they were involved with. At the end of their meal, I said, ‘Excuse me, I couldn’t help but hear your conversation. Any chance of a job?’ They said, ‘Yeah, OK – why not? Come and see us tomorrow morning at 10.’ It was the Scirocco-Powell team, based behind Cliff Davis Cars on Goldhawk Road, Shepherd’s Bush. They had bought some Emeryson chassis and Climax engines, but no longer needed them as they were building their own BRM-powered Formula 1 car for the 1963 season.

Dastle is an acronym of the founder’s name DAvid STanley RumbLE. The company was founded in 1958 by Rumble, first making midget racing cars

“They asked whether I’d be interested in selling all the old stuff, so I went from being waiter to sales manager, put ads in Autosport and Motoring News, sold everything on 10% commission and suddenly had £1000 in the bank, so I bought a Lotus 11.”

James Hunt in the Hesketh March 731, F1 championship, 1973,

Simultaneously, he had befriended a group of racers operating from a lock-up across the street – and their number included Charles Lucas, Piers Courage and Frank Williams. Horsley would subsequently move into a flat in Pinner Road, Harrow, sharing with Lucas, Williams and another racer, Charlie Crichton-Stuart. It was partly a residence, but mostly a magnet for high jinks with an ever-rotating cast of guests sleeping on floors and sofas, not least Courage and Jochen Rindt.

You can barely see the join

“It was through them that I acquired my nickname,” he says. “I bought my Lotus 11 from Bluebelle Gibbs, a well-known driver of the time. Then they started calling me ‘Bluebelle’, which Piers contracted to Bubbles, and it has been that way ever since.”

“Frank Williams went flying off the road. I was so busy watching that I did the same thing”

In 1964 he joined them on the road, trying to scrape a living from start and prize money in the myriad F3 races around mainland Europe – and subsequently wheeling and dealing in all manner of spare parts, which were easily accessible in the UK’s bustling motor sport hub and much in demand among rivals based overseas. “I had quite a big accident at the Nürburgring in 1964, when racing an ex-Steve Ouvaroff Ausper,” he says. “Frank Williams was just ahead of me and went flying off the road into the trees. I was so busy watching that I promptly did the same thing.”

Horsley’s partner in crime Lord Hesketh, left, lights up in the team garage before the 1973 Dutch GP, Zandvoort

Horsley scaled down his own racing activities beyond 1965, but remained involved with the travelling circus for a few more years. “I finally divorced myself from the sport in 1970,” he says. “Of the guys who visited the flat regularly, three had gone on to bigger things. Chris Irwin was terribly injured at the Nürburgring in 1968 [while practising one of Alan Mann Racing’s Ford P68s] and never raced again, while Piers and Jochen died within a few months of each other two seasons later. I decided to go and do something else and accepted an invitation from Nick von Preussen [another racer] to go travelling in a Land Rover, mainly around India.”

In the meantime, he had met Alexander Hesketh for the first time. “That was at Charlie Lucas’s wedding,” he says. “I’d been buying and selling Mercedes-Benzes, Rolls-Royces and Bentleys, and would go to weddings in a Bentley or a Roller to see whether I could sell it to somebody to make a fast buck. When I met Alexander I asked whether he’d like to buy my Rolls-Royce. He wasn’t interested, but wondered if I’d like to purchase his Mercedes, so I gave him pound notes there and then. The following morning, I received a phone call. ‘Is that Bubbles Horsley?

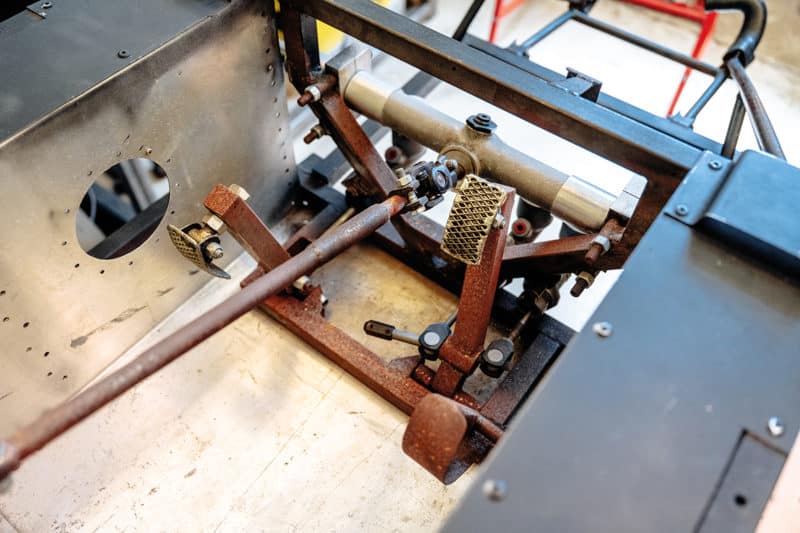

Simple mechanicals in pedal box

I believe you have my Mercedes. Could you possibly bring it back, and please join us for lunch?’ It was his mother, a wonderful lady, and it transpired the car was hers.

“I guess our friendship started in quite a strange way – I did get my Mercedes cash back! – but we still remain very close to this day. After I returned from India I was staying with him one weekend and we talked about setting up an F3 team. I agreed to buy the chassis if he’d cover the engines and that’s how the whole thing began.”

Initially Horsley was the only driver, finishing ninth on his first appearance of the campaign at Oulton Park in April, but generally the car was not competitive – though Steve Thompson managed to make the final when he subbed for Horsley in the Monaco Formula 3 race, having finished eighth in his heat. And then, one week later, at Chimay, Belgium…

Horsley’s year of “hard labour” in the early ’70s was as a used car salesman – Horsley’s Horseless Carriages

“James Hunt had lost his drive with the factory March team following a series of accidents and we were standing next to each other in the Chimay loo, which was basically a tent. I asked what he was doing, to which the reply was ‘not very much’.

“I’d quickly worked out that I wasn’t going to be good enough to move up the ladder, but I knew a bit about James. He had a reputation for being wild, but also very quick, so I asked whether he’d like to drive for us and then went on to have the honour – or perhaps the humiliation – of being his team-mate for a few races.”

The Mark 9 engine

When Hunt raced the Hesketh Dastle for the very first time, at Silverstone in June, he sprinted briefly into the lead – but promptly spun into the pitwall. He also crashed heavily during the British Grand Prix support event, at Brands Hatch. For all that the Dastle was ineffective – or else in bits – Hesketh obtained a better clue about its protégé’s true potential when it hired a March 712 for the British F2 Championship finale at Oulton Park in September; he finished third, beaten only by the newer factory 722s of Ronnie Peterson and Niki Lauda. For the following season, then, the decision was taken to tackle a full year of F2.

Team Surtees had won the 1972 European title with Mike Hailwood, running a TS10, so Hesketh ordered its successor, the TS15. Hunt ran as high as fourth in one heat during the opening round at Mallory Park, before suffering suspension failure, then finished third on his F1 debut the following weekend, when the team rented a TS9B for the Race of Champions at Brands Hatch.

The Mark 9 cockpit

“It quickly became apparent that the TS15 wasn’t the car to have and that we were wasting our time,” Horsley says, “so we began to wonder whether it might not be more productive to have more of a go at F1. If we made a mess of that, fine, we could just get on with the rest of our lives.

“At the Pau Grand Prix, where James failed to start after a practice accident, we went out for dinner with Max Mosley from March to see if we could negotiate the lease of an F1 chassis for the rest of the year. We told him we didn’t have much in our granary, but could offer five bags of grain. He wanted 10 bags and we eventually settled on eight, but then we had to decide how much a bag of grain was worth, so negotiations began all over again.

“We eventually settled on £1000 per bag, so we paid £8000 to lease the car, including gearbox and a full set of suspension spares, bought two DFV engines from Cosworth for £5000 each and away we went to Monte Carlo. Those numbers seem ridiculous now.”

Horsley, right, reunited with the Mark 9 – 50 years on

The team’s approach was reflected in Autosport’s report of that Mallory Park F2 race, in which author Ian Phillips’ description of Hesketh Racing mentions “helicopters and limousines to-ing and fro-ing – it was all very colourful and extrovert, and livened up the scene no end”.

Convention was seldom the Hesketh Racing motif – today Horsley runs an organic granola business named Angry Squirrel – but such frivolities masked the authenticity of the team’s ambitions, particularly when it reached Formula 1.

“I think we ruffled a few feathers when we arrived in Formula 1”

“We weren’t perceived as serious,” Horsley says, “and I think we ruffled a few feathers when we arrived in F1 because other teams didn’t think we were ‘proper’. McLaren team manager Teddy Mayer absolutely loathed us! We worked with a photographer, Christopher Sykes, who was mad about chickens and told us we should always pray to the great chicken in the sky. That’s what we told people we were doing during our early days in F1, when we were all walking around the motorhome, clucking… But that kind of thing really did weld the team together. Plus, of course, when we picked up the car from March we came away with two of their top engineers, Harvey Postlethwaite and Nigel Stroud, both of whom were absolutely brilliant.

Hunt in Hesketh blue at practice at Brands Hatch in July 1972 before a British Formula 3 race. He didn’t make the grid due to an accident

“Whatever people thought about us, there was serious intent within the team.”

That much was swiftly apparent. Hunt finished ninth on his world championship debut in Monaco, then sixth in France, fourth at Silverstone and third in Holland. He retired from the Austrian GP, when his fuel injection system packed up early on, failed to start after a practice accident in Italy and then signed off with seventh in Canada and a superb second at Watkins Glen, less than a second behind Ronnie Peterson’s winning Lotus. Despite taking part in only seven of the season’s 15 grands prix, he placed eighth in the world championship.

The Hesketh March at the 1973 French GP. Hunt, seated, finished sixth, gaining his first championship point. Horsley is in the green shirt

In the space of 12 months the team had gone from F3 lightweight, with the cars you see here, to a serious F1 proposition – a trail unlike any blazed before or since.