1969 through a lens: a spectacular year for racing photography

Many photo archives contain buried treasures – and Paris-based DPPI is one such. It is now bringing some of them to the surface through a series of books, the latest of which covers the 1969 racing season. Simon Arron speaks to Manou Zurini, the main man behind the camera

South African Grand Prix: Graham Hill signs autographs at Kyalami accompanied by a Firestone promo woman. Photographer Manou Zurini found Hill “absolutely charming”. This was the first race of the 1969 F1 season

Fate has a reputation for moving in mysterious ways, but can sometimes be unexpectedly productive. When watchmaker and motor sport aficionado Richard Mille visited the DPPI archive to seek bygone images of racing cars in his own collection, he and DPPI’s managing editor Fabrice Connen were swiftly diverted by the breadth of content on the contact sheets before them – and the fact so many of the images were unfamiliar.

Zurini (left) with Jean-Pierre Jarier in his Shadow at Interlagos in 1975

Thus were the seeds sown for a series of books throwing fresh light on our sport’s past. Published in 2018, the first of them covered 1965, the agency’s inaugural year of existence, and the newest – fifth in the series, just released – showcases 1969.

British Grand Prix: Jackie Stewart gives his version of an epic Silverstone battle with Jochen Rindt, which ended when the Austrian driver had to pit with a loose rear wing. “I shot quite a lot in the UK,” says Zurini, “because it had more races than anywhere else!”

Emmanuel ‘Manou’ Zurini was DPPI’s chief photographer for more than a decade from the mid-1960s. “Some of the photos I took at the time – a mechanic eating a sandwich, for instance, or changing gear ratios in the grass, were put on one side because they weren’t considered particularly interesting,” he says. “Nowadays, however, they are perceived as treasures.”

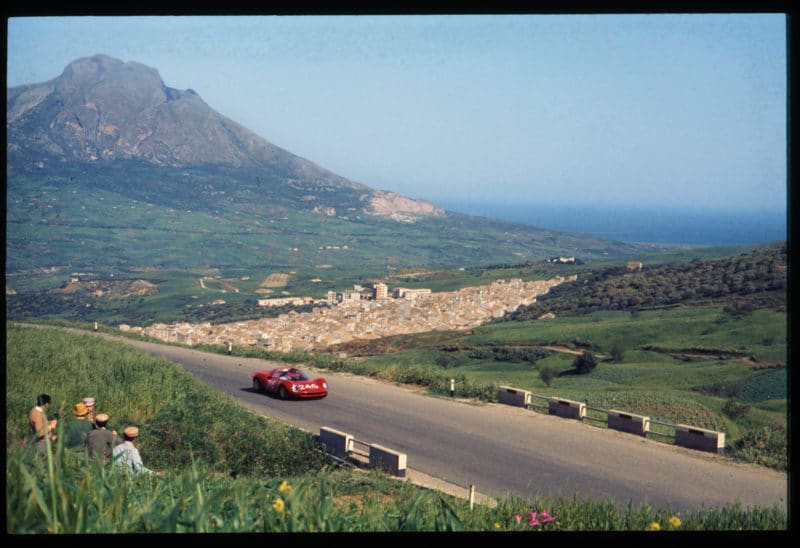

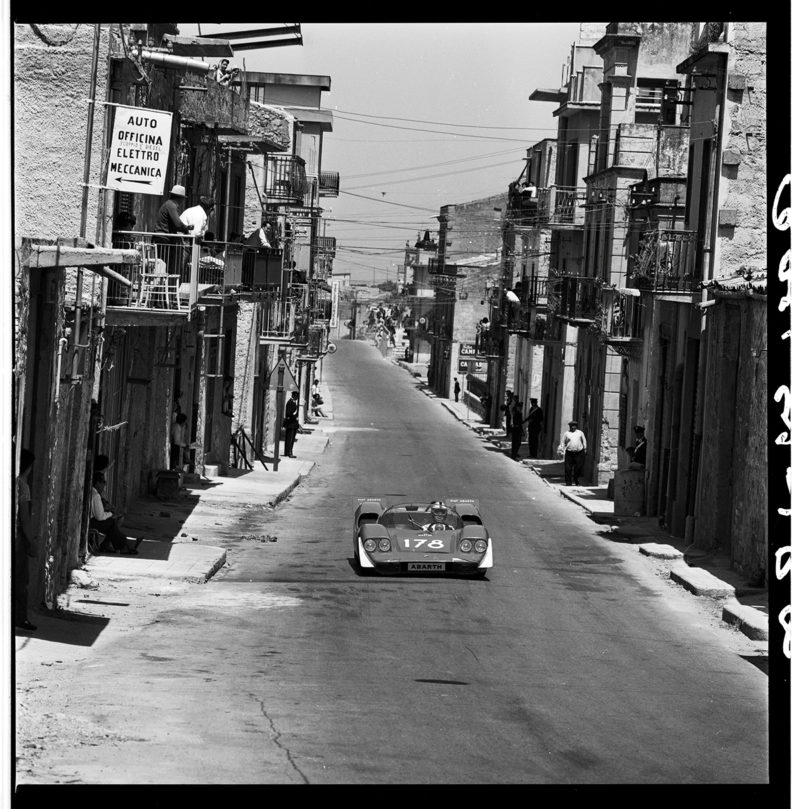

Targa Florio: The full magnificence of Sicily, with the Ferrari 206 Dino of Leandro Terra and Turillo Barbuscia as a foreground detail. They finished 25th overall, two laps – almost 90 miles! – behind the winning Porsche 908 of Gerhard Mitter and Udo Schütz. “I absolutely loved that era of sports car racing,” says Zurini. Not hard to appreciate why…

His own role in the DPPI story came about through chance.

“A friend bought an Alfa Romeo Giulia Ti, the Alfa equivalent of a Lotus Cortina but heavier, so not as quick – and started competing in minor events. His mother lent me her Kodak Retina folding camera, so I used that to cover his racing and was soon framing shots correctly and capturing a sense of motion.

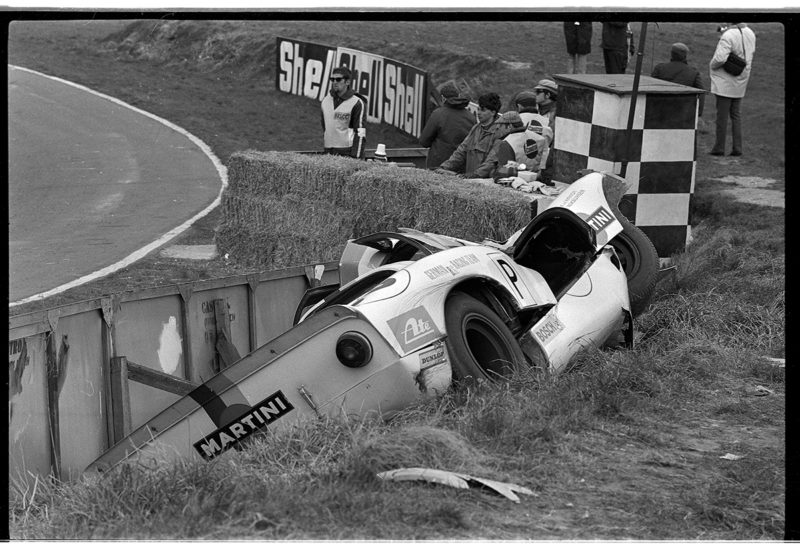

BOAC 500, Brands Hatch: While the race was a triumph for the factory Porsche 908s, which took a clean sweep of the top three places, it was less productive for the privately entered 907 of Rudi Lins and Willi Kauhsen. “I absolutely loved shooting at Brands,” says Zurini. “It was one of my favourite tracks”

“Subsequently I met Jean-Pierre Beltoise at the Circuit de La Baule-Escoublac, close to where his family had a home [by the Atlantic coast], and started following his exploits, too. That continued through F3, F2 and into F1 – so much so that I was on the truck with him during his victory parade after he won the 1972 Monaco Grand Prix!

South African Grand Prix: Overhead view of the boss at Kyalami, another of Zurini’s favourite tracks for photography. Bruce McLaren went on to finish fifth in the opening world championship race of the F1 season, a lap adrift of Jackie Stewart’s winning Matra

“The Beltoise family was quite well off and his mother enjoyed travelling. One day, Jean-Pierre told me his mother was going to Japan and asked me to prepare a list of photographic equipment I’d like her to bring back. I was using Pentax equipment by then and requested two bodies, a 400mm telephoto lens, an 80-200 zoom, a wide-angle and everything else I needed. She brought it back with her two months later and passed straight through customs without any questions being asked.”

Coupe des Alpes: Unveiled in 1955, the Citroën DS still looked the part 14 years later – and is far more elegant than many cars produced today. The DS21 of Bob Neyret/Michèle Veron finished 10th on an event that ran from Marseille to Juan-les-Pins

On May 1, 1966 Zurini was photographing the traditional bank holiday meeting at Magny-Cours. “I was at the final corner,” he says, “and took a series of shots when Jacques Bernusset’s F3 Cooper left the road, unfortunately with fatal consequences. A nearby photographer came over. His name was Daniel Paris and he said, ‘We have an agency, DPPI. I also saw you in action at the Le Mans test weekend and you seem to know what you’re doing. Here’s my card, so why don’t you come and see us?’”

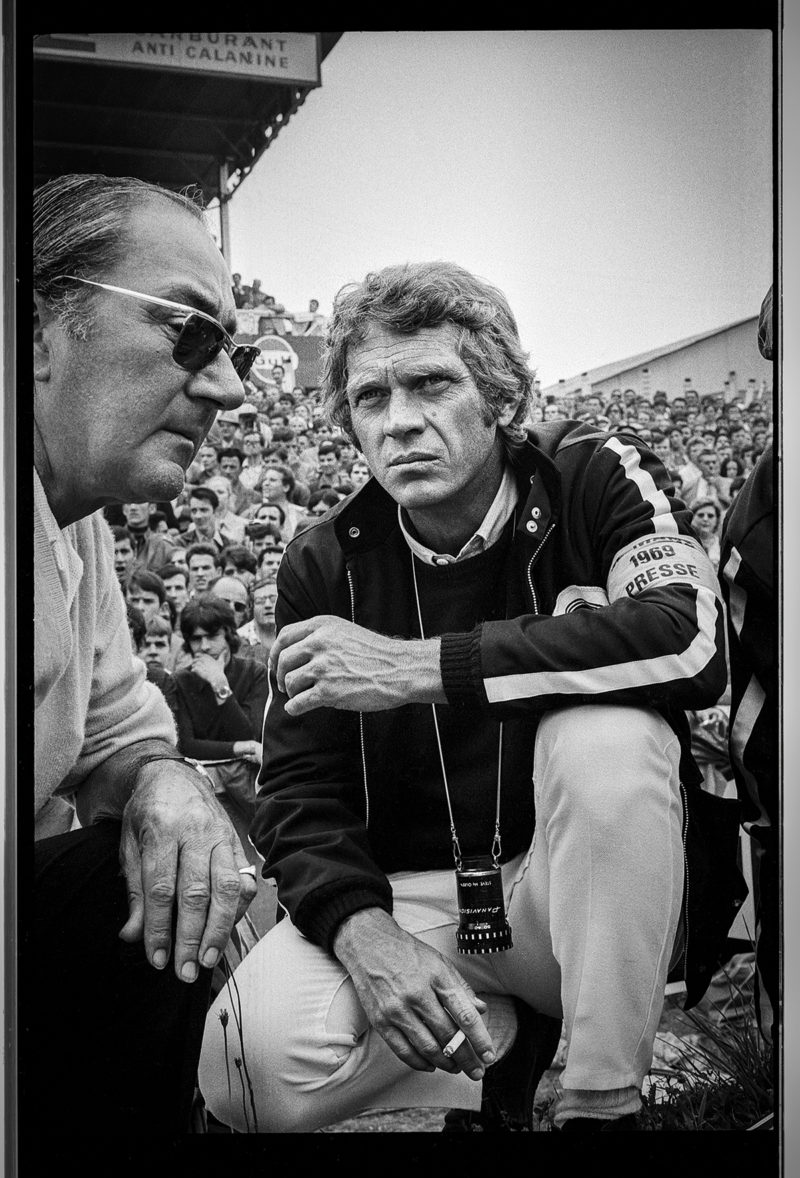

Le Mans 24 Hours: Possibly the most famous person to be granted a press armband… Steve McQueen on a fact-finding mission a year before filming of Le Mans began. Zurini had himself previously featured in John Frankenheimer’s Grand Prix… as a photographer

He did and, one weekend later, was on his way to Zolder, to cover a double-header featuring F2 [the Grote Prijs van Limborg] and the European Touring Car Challenge.

“I travelled by train and then hitch-hiked 80 kilometres from Brussels to Zolder, which was quite an undertaking. I had four rolls of colour film with me and eight of black and white – a bit different from the final phase of my career, when I’d have 40 rolls of Kodachrome costing at least £10 per roll.

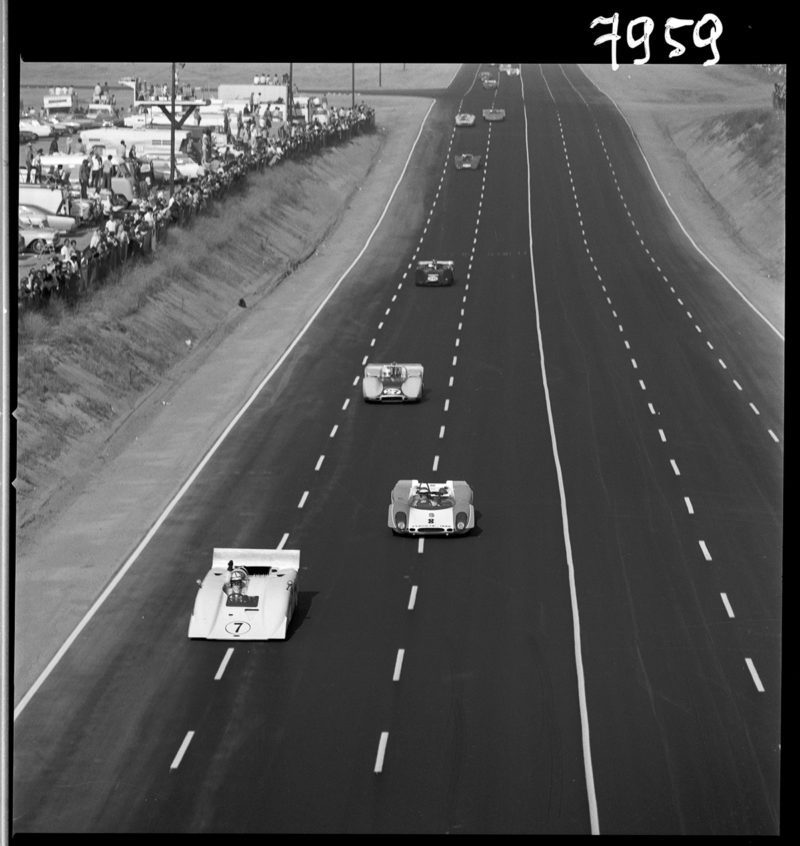

Los Angeles Times, Grand Prix: “Intense racing in a relaxed atmosphere…” is Zurini’s take on Can-Am, a series he photographed on numerous occasions. John Surtees (Chaparral 2H) leads compatriot Tony Dean (Porsche 908/02) at Riverside. Surtees retired early with a blown engine; Dean took seventh

I always worked with Kodachrome, which was 25 ASA, so very slow film. Without decent natural light, I couldn’t take photos!

“During that weekend I got a shot of Jochen Rindt completely sideways in an Alfa Romeo GTA, hands visible on the wheel while he was on full opposite lock, and that made the front of Belgian magazine Virage Auto – a first cover shot for both me and DPPI.”

Le Mans 24 Hours: Johnny Servoz-Gavin, above, failed to finish at Le Mans in this Matra MS650 shared with Herbert Müller, but won the 1969 European F2 title. Concerned about an eye injury, sustained away from racing, he quit the sport after the following year’s Monaco Grand Prix

The company’s acronym originally blended Daniel Paris and Publi-Inter, the name of co-founder Jean-Pierre Thibault’s advertising agency and publishing business. Paris moved on quite swiftly, however, and its full name was revised to Diffusion Presse Photo International, with Zurini as its trackside spearhead.

Rallye Méditerranée: Monte Carlo was two rallies in one – the main event, plus a separate contest for non-homologated cars. Matra ran MS530s for a star-studded team including Jean-Pierre Jabouille, top right, Jean-Pierre Beltoise and Henri Pescarolo, but all failed to finish

As the images in 1969 reflect, his brief was broad. “I loved endurance racing,” he says. “The quickest cars were similar to their F1 counterparts in performance and many of the drivers were the same, too. It was a fantastic era, much more accessible than it has been for many years, and I was able to do everything I wanted as a photographer. And then we had events such as the Targa Florio, with its fabulous backdrops.

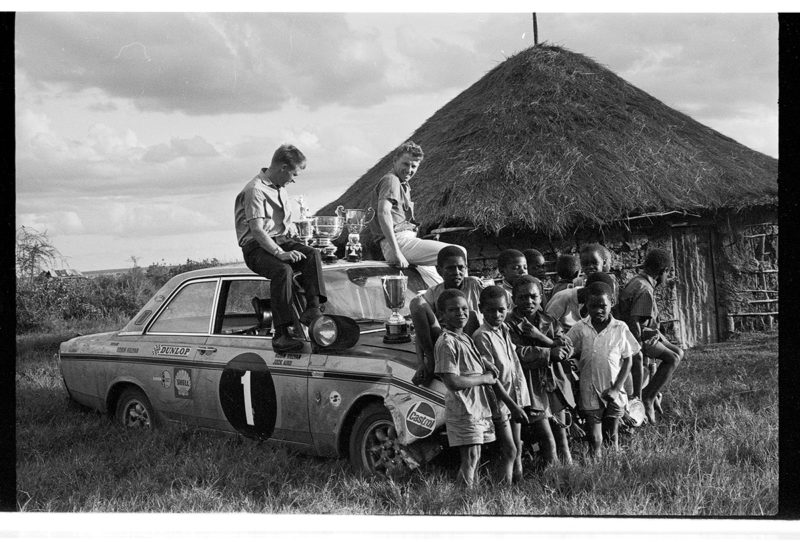

Safari Rally: Kenyans Robin Hillyar and John Aird, centre right, pose with local children and their slightly battered Ford Taunus. They went on to beat Joginder Singh/Bharat Bhardwaj (Volvo 142) by more than half an hour. There was still no formal world championship at this stage

“I did a few rallies, but if I’m honest they weren’t my favourite jobs. Sometimes you’d drive quickly through the night for 200 kilometres to reach a stage… but arrive to find the leading cars had already passed through. And with the technology of the era the flashgun tended to fire only every other shot, so it wasn’t really my thing. I was much happier at a track.

Mexican Grand Prix: At the end of a Formula 1 campaign dominated by Jackie Stewart’s Matra, Denny Hulme, right, celebrates giving McLaren its sole world championship win in Mexico City’s season finale. Long after clinching his maiden title, the Scot finished a distant fourth

“I also got to shoot quite a few Can-Am races – in the era of Bruce McLaren and Denny Hulme with their McLaren M8s, too. That was incredibly impressive – intense racing in a very relaxed atmosphere but I think North America is still like that today, if you listen to how much guys like Romain Grosjean and Simon Pagenaud are enjoying IndyCar.”

Le Mans 24 Hours: Perfect timing as Zurini captures Jo Siffert, above left, standing out from the crowd before the last-ever running start at Le Mans. In protest at what he felt was a dangerous procedure, Jacky Ickx walked across the track and started last… though he and Jackie Oliver still won

Zurini stayed with DPPI for 12 years before accepting an invitation from Elf’s influential marketing manager François Guiter to become the company’s photographer.

Le Mans test: Paul Hawkins, above, and his team are at work on his Lola T70, in which he was third fastest during the traditional pre-race test on March 30. By the time the race came around, the Australian was no longer alive. He was killed while contesting the RAC Tourist Trophy at Oulton Park

“By then,” he says, “I think some of what I was doing for DPPI had perhaps become a bit formulaic – the same start shots, the same podium shots. Elf just wanted nice photographs and told me I could do whatever I wanted. I enjoyed shooting in the rain, which I felt added a certain something, but with Kodachrome I still required good light. If it was a damp, dark, grey day, I’d just sit in the motorhome chatting to François and wouldn’t take any photos at all.”

Targa Florio: Around the houses: the Abarth of Erich Bitter and Helmut Kelleners, left, screams past Sicilian doorsteps as locals capitalise on the view from their balconies. The Germans finished a class-winning eighth overall. If ever an event was tailor-made for wide-angle lenses, the Targa was probably it

Zurini bowed out of racing completely after the 1996 season. “Bernie Ecclestone had decided there were too many people in the paddock,” he says, “and his henchmen started a cull. As I’d been working only for Elf, and hadn’t been with a press agency for quite a long time, I was one of those to get the boot.

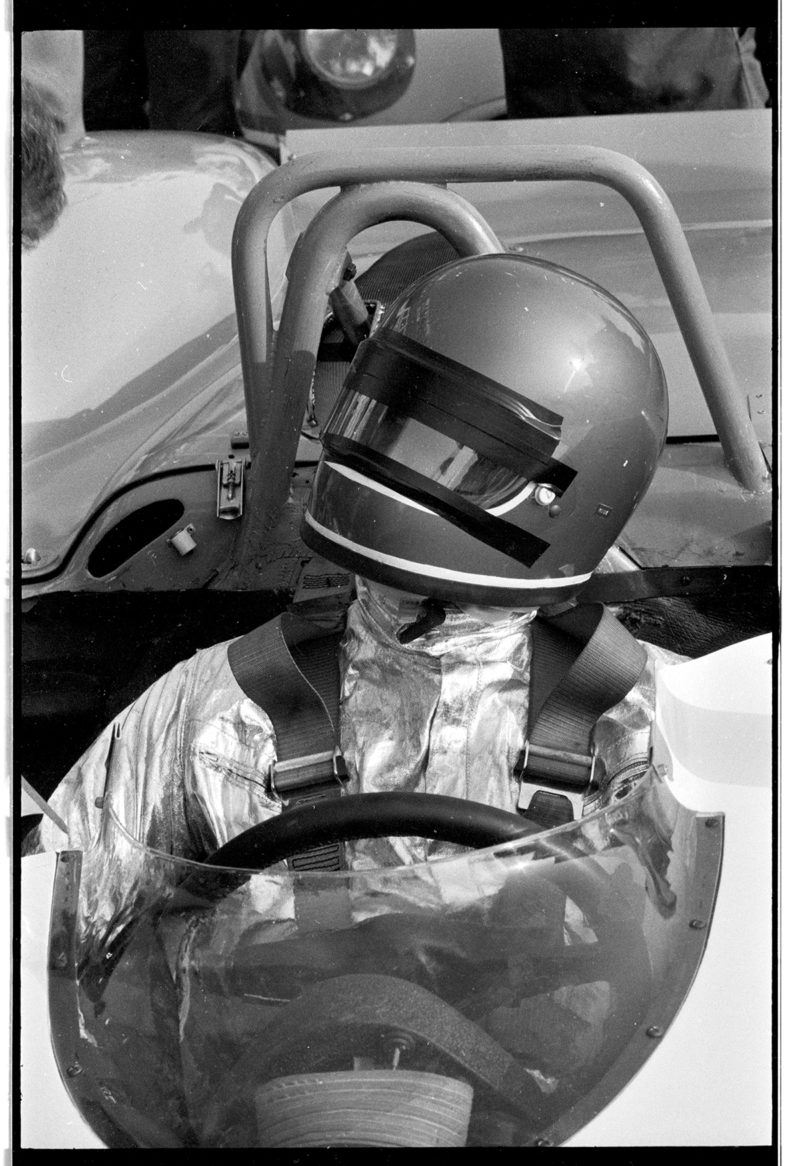

Dutch Grand Prix: Up close with Jo Siffert, who had a very busy year. As well as a full Sports Car World Championship campaign with Porsche, for whom he took six victories, the Swiss completed a full grand prix programme with Rob Walker Racing. Here at Zandvoort he took his Lotus 49 to second

“François had stepped away from F1 the previous year and this would never have happened if he’d still been around, because he was close to Bernie and had helped with various innovations, including the introduction of small on-board cameras. But he wasn’t, so I told F1 where to go and took up sculpture instead. I do still take photos, but only for my own use…

“I am very well aware, though, of how privileged I’ve been. I was earning a living by travelling around to photograph racing cars. What could have been better? And I was reasonably well known at the time, too, so had good access to the teams and they left me to my own devices. I thought it was the best job in the world.”

Views of the ’60s

The fifth instalment of DPPI’s

Car Racing series, Car Racing 1969

by Manou Zurini and Alain Pernot, is published this month by Éditions Cercle d’Art, priced at £85.

It is available to buy via the publisher’s website: cercledart.com