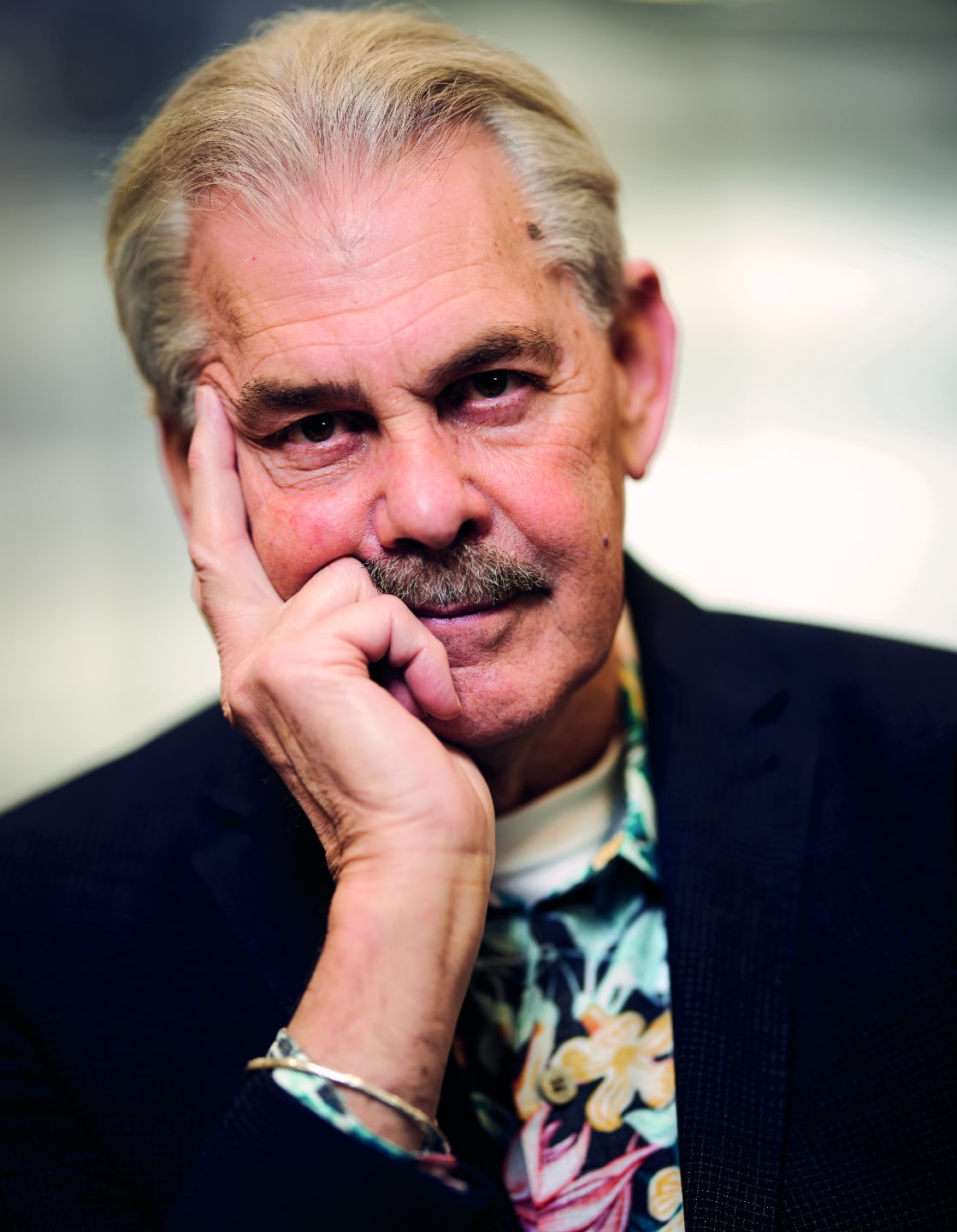

Gordon Murray: The Motor Sport Interview

Motor racing has had more than its fair share of gamechangers, but within that select group the Brabham and McLaren designer rides high – and Gordon Murray hasn’t finished yet

RICHARD DAVIES

In December 1969 a 23-year-old South African engineer came to England to look for a job, boarding a coach to Norfolk in the hope of work with Lotus. They were laying people off however and now he was living in a bedsit with no money. So he went to the Brabham factory where Ron Tauranac thought he’d come for an interview for a vacancy in the drawing office and gave him the job. After 16 years at Brabham, winning two World Championships, he moved to McLaren where his cars won a further three titles with Prost and Senna.

By 1991 Murray was ready for a new challenge, having brought refuelling, air jacks, revolutionary suspension and aerodynamics, and new materials to the sport before leaving the pitlane to design the McLaren F1 road car. Keen to satisfy his hunger for ever more innovative and disruptive engineering Professor Gordon Murray CBE (for services to motoring) established his own company in 2007 and revealed the T.50, his 50th car, in 2019. Today Planet Murray has its headquarters at Shalford, Surrey and a new manufacturing campus at nearby Dunsfold Park – from where he looks back on his extraordinary career.

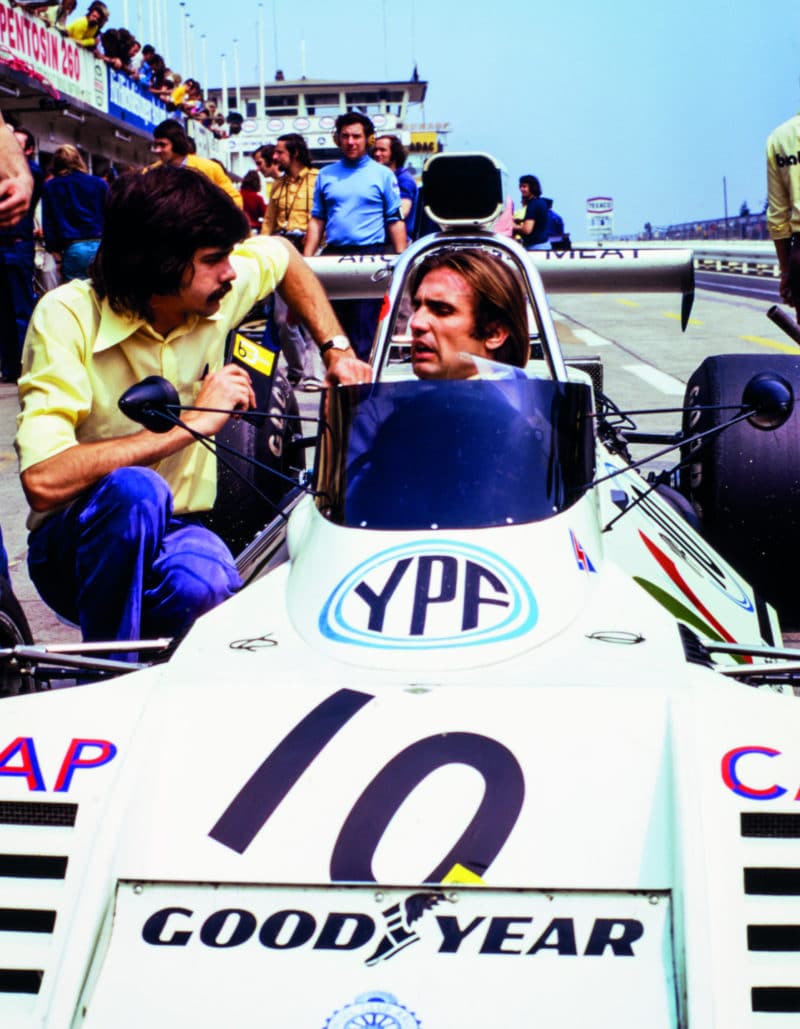

Carlos Reutemann, seated, in a Brabham BT42 gives feedback to designer Gordon Murray at the Nürburgring in 1973

Grand Prix Photo

His first ever sports car, the IGM-Ford from 1967

RICHARD DAVIES

Pens, compasses, rulers, hole punch – the desk of Gordon Murray

RICHARD DAVIES

Motor Sport: As a teenager in Durban you had designed, built and raced your own car, the T.1, so why did you pack your bags and come to England in the depths of winter?

GM: “Music and motor racing, the loves of my life, that’s what brought me here in a freezing cold winter, ice on the pavements, and I hadn’t brought a proper coat. In the late 1960s there was so much great music and of course it was the place to be for racing. I was first and foremost an engine designer but what I really wanted to be was a racing driver. I’d won some races in South Africa, been national champion in a car I designed and built, but my height and weight were against me and I never had enough money. So I’d written to Colin Chapman and got an appointment to see Brian Luff at Lotus before I arrived in England.

“I couldn’t believe it, Formula 1, and I was 23 years old“

“I went to Norfolk by coach because at home we still had steam trains, and they were slow, so I thought the coach would be faster. That turned out not to be the case. Anyway, Lotus weren’t selling any cars, there was a mini recession, so there were no jobs. Not for a minute did I think I’d get into Formula 1 at that stage so I started building a little sports car, the T.2, and I almost took a job at Ford – but when I saw the design office, drawing boards everywhere, there was a guy drawing a door handle. I knew I didn’t want to do that having designed my own cars.

“Then I saw a job advertised at Fairoaks Airport where Alan Mann was based, and Len Bailey was working on the Ford F3L. We talked but he decided they didn’t have the budget for another designer and then, a week later, he changed his mind… so I went to see him again. While I was there one of his guys told me, ‘Len will never make up his mind and there’s a job going at the Brabham Formula 1 team so you should go down there.’ So I did, knocked on the door, and Cathy the receptionist showed me to Ron Tauranac’s office in a Portakabin. I told him all my academic qualifications but he wasn’t at all interested – very Tauranac. Then he showed me a metal part and asked me how I would make it, so I told him, in detail, and he said, ‘Fine, you’ve got the job.’

“As I was leaving a much older guy turned up for the job interview. Tauranac had got the wrong person so I was in the right place at the right time. I couldn’t believe it, Formula 1, and I was 23 years old.”

This was your big break and the rest, as they say, is history. Bernie Ecclestone bought the team, fell out with Ron Tauranac, made you the chief designer in 1972 and gave you absolute creative freedom.

GM: “Well, Bernie tells people that Tauranac advised him not to keep me on so the first thing he did was make me his chief designer. He loves a good story. Nearer the truth is that I’d had an offer from the Pederzanis who’d come into F1 with Tecno and a flat 12 engine which was a bad Ferrari copy. He wooed me with a house in Italy, twice my salary, but I turned him down. Alain de Cadenet was also talking to me about a car with a Cosworth DFV for Le Mans and I think all this got back to Bernie who fired all the other guys and said, ‘Right, you’re now the chief designer. I want a brand new car for next season.’ I told him I’d agreed to do the car for de Cadenet and he said, ‘Okay, you can moonlight that.’ So I was working ridiculous hours, finishing at Brabham at 9pm, working on the de Cadenet car until 3am and then back to Brabham for 7.30am.

“I don’t accept that the BT55 was a failure. The concept was dynamite“

“That winter living in an unheated flat was hell but Alain’s car really helped launch my career. At Le Mans we annihilated the Porsches and the Alfas, running just behind the Matras. We did the whole thing, including buying the DFV, for less than £5000. Alain offered me £250 to design it and a half share in the car – but when he sold it, I think he forgot about that. Those first two years in England were incredible… I designed four cars – my own Formula 750 club racer, my Mini Bug road car, the Le Mans car and the Brabham BT42. I still wanted to race and 750 was basically a free formula so I designed a radical car, lay-down driving position, 284kg, and I found a way of making the body a monocoque although you weren’t really supposed to do that within the regulations. Once Bernie had promoted me I just ran out of time to go racing – but I still have the car, the T.4, the de Cadenet car being T.3.”

The Brabham years gave you total freedom to express your creativity and your innovative ideas despite being so young. Was that something you demanded when you became chief designer?

GM: “Bernie trusted me. He likes to find that ‘unfair advantage’ just as much as I do and he’d picked me because I was innovative during the time I worked for Tauranac. Most of all, Bernie is a racer, and he let me go out on a limb. The early cars, BT42 and 44, were like no other grand prix car. They were tiny, short wheelbase, very small track, wacky aerodynamics, lots of fuel behind the driver for the first time. They were very different, he loved all that, and just let me get on with it. We were constantly looking for ways to be better than everyone else, not by a little bit, but by a lot.

It wasn’t about looking for loopholes in the rulebook, it was about innovation, about the way you approached the design process, a state of mind, how you can improve what’s gone before. A good example is rising rate rod-operated suspension, an innovation on the BT44. Everyone was using those stupid rockers but they are an un-damped spring, the most horrible things, and now every single car uses pull or push rod suspension.

“We had a couple of failures but as an innovative engineer you have to accept that and learn from it. I don’t accept that the BT55, the low line car with the BMW engine tilted on its side, was a failure. The concept was dynamite, but the problem was that neither [engineer] Paul Rosche of BMW nor I could get the oil scavenging to work. All the oil got stuck in the head, and we could never get the oil temperature under control. Also, it was the first all-carbon tub, a very long wheelbase, and in retrospect it just wasn’t stiff enough. However, I took the drawings, the exact same geometry, to McLaren at the end of ’86, where we had a nice little Honda V6, and when we put the MP4/4 in the tunnel the aerodynamic results were magic, so much better, around a second and a half per lap better.”

Bernie Ecclestone allowed Murray creative freedom at Brabham, which led to a slew of innovative designs

RICHARD DAVIES

Reutemann in the wet before the 1975 Dutch Grand Prix, with Murray and Ecclestone in attendance

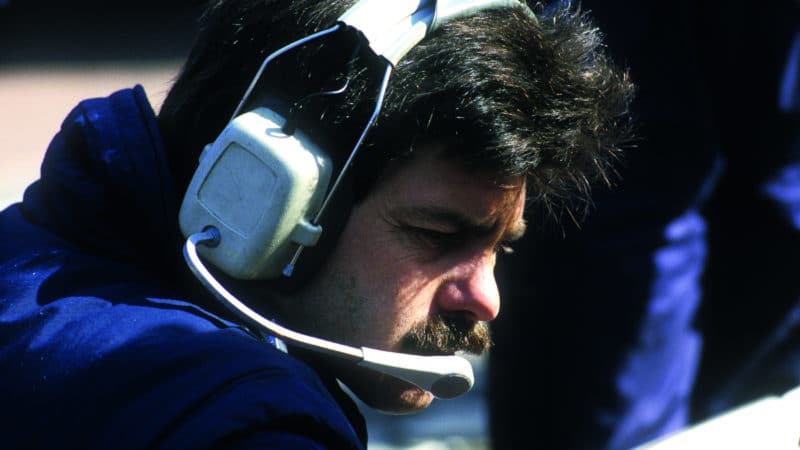

Murray in 1982: a tough year for Brabham with frequent retirements, albeit with two first-place finishes – Monaco and Canada

We should mention the Brabham ‘fan car’, the BT46B, because it was not only highly effective but also highly controversial. What led you to putting a fan on the back of the car?

GM: “It was desperation actually, absolute desperation, because in ’78 it was dawning on us how the Lotus worked, with the venturi and the wing ‘pods’ all the way down the car. When I laid a typical wing section out on our BT46, the bit where the venturi turns into the diffuser was right where the cylinder heads of the engine were because the flat 12 Alfa engine was much bigger and wider than a DFV or a Ferrari. I said to Bernie, ‘We’ve had it because we’re never going to get a clear wing section like the Ferrari or the DFV-engined cars.’ So, the first idea I had was to do a twin monocoque car. The bulkhead finished behind the driver and the engine was bolted to the bulkhead, then there was a second small monocoque which bolted to the back of the engine, which held the fuel tank. A quill shaft ran through a tube in the tank and then the gearbox went on the back of that. This now moved the cylinder heads of the engine into the lowest part of the venturi but I worked out this would be 25-35kg heavier and very complicated to work on. So it was a mess and back to square one.

“I read the FIA rulebook again and landed on the infamous article on aerodynamics. ‘Any device whose primary function is to have an aerodynamic influence on the performance of the car has to be firmly attached to the sprung mass.’ So, a fan driven through the gearbox would cool the radiator, which was mounted over the engine, as well as create downforce. When the FIA measured the flow of air through the fan and through the radiator they found that 60% of the air was for cooling and 40% for downforce, meaning that aerodynamics was not the fan’s primary function. That’s how the BT46B came to be.”

You worked very closely with Nelson Piquet and Niki Lauda at Brabham and with Prost and Senna at McLaren. Which of these gives you the most satisfying memories?

GM: “I think it has to be Nelson because he came to us as an apprentice, if you like, from Formula 3 and stayed with us for seven years. He was very much part of the family and of all the drivers, he got much more involved with the team. Later on the drivers started being treated like gods, which I didn’t like. They’d come and go as they pleased. Nelson came to the office every single day on his bicycle. He’d rented a flat near Chessington and he’d come to the factory, and sit on the corner of my desk asking me why I was designing this or that. He came to every windtunnel session and of course he won two World Championships which speaks for itself. He’s the one I remember most fondly. He was the most rounded, but of course it was also great working with Niki, Ayrton and Prost later on.”

How important was good feedback from the drivers when you were engineering your grand prix cars?

GM: “Very important. I mean, in the early days Bernie would put a pay driver in the second car and most of them, their feedback was non-existent. There was no telemetry so you relied totally on what the driver was telling you about the car. It’s far easier to interpret what they say if you’ve raced yourself, and you know what a car driven over the limit feels like, what understeer or oversteer means to you. Nowadays everything is measured for you, and there’s a computer that tells you what to do with the car, so it’s totally different.”

Alain Prost, leading, and Ayrton Senna dominated F1 in 1988 in the McLaren MP4/4

Grand Prix Photo

At the end of 1986 you moved to McLaren when John Barnard went to Ferrari. How far were you able to take full control of the design and engineering processes under Ron Dennis?

GM: “After 17 years I thought I’d had enough of Formula 1. We’d won two World Championships, and I was already thinking about designing some sort of supercar. But… Ron had lost Barnard to Ferrari and he was desperate for someone to head up his design team. My first reaction was absolutely not. I’d had enough. In my last year at Brabham we’d lost Elio de Angelis. I’d never lost a driver before. Bernie was heading towards running Formula 1, he’d lost interest, so it was time to go. Ron was very persuasive, however. So I finally agreed and told him I wanted to be in charge of everything technical, design, testing, procedures, systems, composites, wind tunnel – whatever, it was, I wanted to be in charge of it, not as chief designer but as overall technical director. Not only that, but I would only do it for three years. That’s enough for any human being. He agreed, gave me absolute freedom.

“The first thing I did was buy three autoclaves and set up a composites department – we’d had one at Brabham for years. The ’87 car was already done, so I was stuck with that, and we won a few races. Neil Oatley was my main man. He had fantastic experience. So he and I sat down and looked at the next two years which were incredible – the TAG-Porsche for one year, then the Honda V6, and then the change to normally aspirated. We had to design four cars in 18 months. I led the design team, putting Neil on all the normally aspirated cars and Steve Nichols on the ’88 car.

“I am sick and tired of all the people living off my reputation“

“I am so sick and tired of all the people living off my reputation, you know. This thing about Steve Nichols being chief designer is the biggest load of rubbish you’ve ever heard. The MP4/4 was not designed by Steve Nichols, I can promise you that. I put him in charge of the monocoque and the front end while Dave North and I did the rear end, the aerodynamics, and a radical new dry-sump three-shaft gearbox working with Pete Weismann. It was a pretty radical motor car. I’d taken the Brabham BT55 drawings with me to McLaren so the basic concept of the MP4/4 was the BT55, with the lay-down driving position, and a far better rear end, with the Honda V6, and then I also designed new front suspension, using a pull rod with a roller and track system. If you look at the two cars together, the BT55 and the MP4/4, you’ll see the design is almost identical.

“The McLaren was a pretty radical car which won 15 of the 16 races in 1988, not just because it was fast, but because we’d brought in a whole range of new systems to ensure reliability. I introduced post-race meetings, captured all the things that cracked or broke with a life-ing system, gearbox rigs to monitor the passage of the oil, a new way of torsion testing the engine and the chassis, plus I had a separate test team set up in Japan.”

Looking at Formula 1 today, the regulations are very prescriptive, little room for creativity and innovation, and technically it seems oddly sterile. What changes need to be made do you think?

GM: “We spoke about this many years ago and I recommended quite a long list of changes that could be made to reduce costs and improve the racing. [See Murray’s ideas for F1 in Motor Sport, September 2012].

“It’s really funny because many of them have been adopted. I’m not saying that’s because of what I said back then, rather I think it was the natural way to go. I stand by everything I said at the time but what I will say now is that one of the most ridiculous and costly things is the 13in wheels. The rest of the world has gone to 18in wheels –I mean, trying to package carbon brakes in a 13in wheel is just stupid. So, not before time, they are changing the wheel size, but I agree that there is far less room for innovation and creativity than there used to be.”

Let’s talk about road cars. The McLaren F1 and now the new T.50, just two of the 50 cars you have designed and built. Were these always part of your long-term plans?

GM: “Yeah, probably from when I was a teenager. I’ve always loved styling, as well as the engineering, and when I first saw a Lamborghini Miura I thought, ‘Wow, I’d love to do the ultimate sports car.’ Luckily Mansour Ojjeh and Creighton Brown at McLaren were very supportive and Ron Dennis also wanted to expand the group beyond just an F1 team. He didn’t want me staying in F1 and working for the opposition… so, after I’d done my three years in the team, he was keen for me to do the road car. I always wanted the central driving position, I still do, and ‘speccing’ that BMW V12 engine with Paul Rosche, where I was able to have a lot of influence, was very satisfying. The fact that it went on to win Le Mans and world championships is what makes me the most proud of that car. It was never designed to do that. I had an F1, of course, but I sold it four years ago.

After the T.50, there is still another car to come from Murray – and it will be electric

RICHARD DAVIES

Murray believes the ‘analogue’ T.50 is superior to his McLaren F1 road car

RICHARD DAVIES

“The T.50 is a better car but the McLaren F1 won Le Mans and you can never take that away from it. I started Gordon Murray Design in 2007 and among many other projects, we’re building T.50 prototypes. I think the T.50 will be the last great analogue car from a sheer driving and engineering point of view. I’ve worked closely with Cosworth on the engine from the ground up, nothing borrowed. I think also it will be the last great V12 – 3.9-litre, 12,000 revs, an engine throttle response time of 28,000 revs per second, so in a lightweight car like the T.50 you get that instant punch, the way it just barks into life. You only get that with a normally aspirated engine and it can’t be replicated by anything else. It’s a great engine and I really can’t see anyone else doing another V12 in the future.”

“We’re building 12 prototypes of the T.50, then we’ll do a handful of pre-production cars for homologation, media work, teaching people for service and after-sales. Then from January next year we start the production line. Of course I would love to race the car. Sadly there’s nothing for us in the new regs at Le Mans but we are talking to Stéphane Ratel about his GT series. We’re incredibly busy, starting a new electronics business alongside our core business which is the iStream manufacturing process that I invented when I started working with composites and realised their potential for cars which are both strong and lightweight. Since 2007 we’ve gone from just eight people to 160 and by the end of the year we will have 250 staff across the group. Next month we’re starting an iStream electric vehicle project so the T.50 won’t be the last car I do.”

Kokusai Aihatsu Racing McLaren won Le Mans 1995 in the hands of JJ Lehto, Yannick Dalmas and Masanori Sekiya

Sygma via Getty Images

RICHARD DAVIES

Everyone is talking about the end of fossil fuels but some of us are reluctant to buy an electric car right now. How do you see the future for the car industry?

GM: “Unfortunately we are having electric cars pushed upon us when they have the wrong

battery technology. For electric cars to be truly good you need two things: you need enough clean energy to plug them into and you need the next generation of batteries. The energy density is so poor with the current lithium ion batteries and you’re lugging around hundreds of kilos of dead weight. The honest truth is, petrol is just too good. Petroleum is so energy dense. A typical air to fuel mixture in an internal combustion engine is about 15 to one so you only carry the one unit of petrol, and the 15 units of air are just all around you for free. With electric you need 9000 cells, half a ton of battery like a Tesla, and it’s only 15% efficient. You’re carrying that weight around all the time.

“Right now, electric cars are not an attractive proposition“

“I know we can’t go on using petrol for ever but right now electric cars are not a terribly attractive proposition. If we jump forward 30 years, when we are making green energy everywhere, and we have batteries with three times the energy density, then they start making sense. So right now we are having electric cars forced upon us too early – they are too heavy, some weigh more than two tons, and the tyre and brake wear is horrendous. They are simply a stop gap.”

“Hydrogen would be the perfect answer, but it takes so much energy to make hydrogen, and we need to find other ways to make it. Then there’s the infrastructure, the storage of highpressure gas which can be dangerous, but we can get over these problems given time. At the moment making a litre of hydrogen uses more oil than it takes to make a litre of petrol. Assuming we can get round all these issues hydrogen might well be the answer. Due to climate change electric is upon us much earlier than it should be.”

When we started talking, you said you came to Britain for the motor racing and the music. Are you still playing in a band when you’re not making cars?

GM: “Music is always in my life. I play guitar and drums, and my band lasted until 1988. It was called Missing Money because we reckoned we had the sex, drugs and rock’n’roll but not the money. Anyway, I have a wonderful collection of vintage jukeboxes, a 1954 Seeburg HF100R sits next to the drawing board in my office. You could get them for hundreds of pounds years ago, now they’re worth many thousands. I also have a huge record collection, and a great sound system, so yeah, music is still very much a love of my life.”