Family fortunes: Julian Bailey and his pioneering motor sport family

Few working class people compete at motor sport’s top level, yet Woolwich-born Julian Bailey has rubbed shoulders with the best. Over a drink or two, the Rat Pack racer – with sons Dan and Jack in attendance – tells Damien Smith how he did it

Andrew Ferraro

Julian Bailey was always the dark horse of British motor sport’s 1980s ‘Rat Pack’. A tough, dour working class lad born and bred in a council house in Woolwich, he beat all the odds to claw his way to Formula 1 – as did comrades and rivals Damon Hill, Mark Blundell, Martin Donnelly, Johnny Herbert, Johnny Dumfries and Perry McCarthy (just). But Bailey never felt he truly belonged at the pinnacle (as he tells us, perhaps it was a class thing), and with just seven F1 starts to his name – six with Tyrrell in 1988 and another for Lotus in 1991 – this is a career best remembered for the raw promise of its early years, a Group C cameo with Nissan, Toyota tin-top shenanigans in the British Touring Car Championship’s golden era, a fruitful Indian summer in a Newcastle United-backed Lister Storm and a final flourish with MG at Le Mans in 2001 and ’02. It sure was colourful, certainly never dull – and it could and should have been so much more.

But the Bailey motor sport story is far from spent. The family’s racing roots are buried too deep for that to be the case. Wife Deborah Tee remains a highly-respected PR through her MPA agency, brother-in-law Steven Tee is one of F1’s finest photographers – just as his father Michael Tee used to be – and then there’s Indy 500 winner Gil de Ferran, who’s married to a cousin of Deborah and Steven. But most significantly, Julian’s sons are now carrying the torch, even if it’s in a manner that leaves the old man scratching his head.

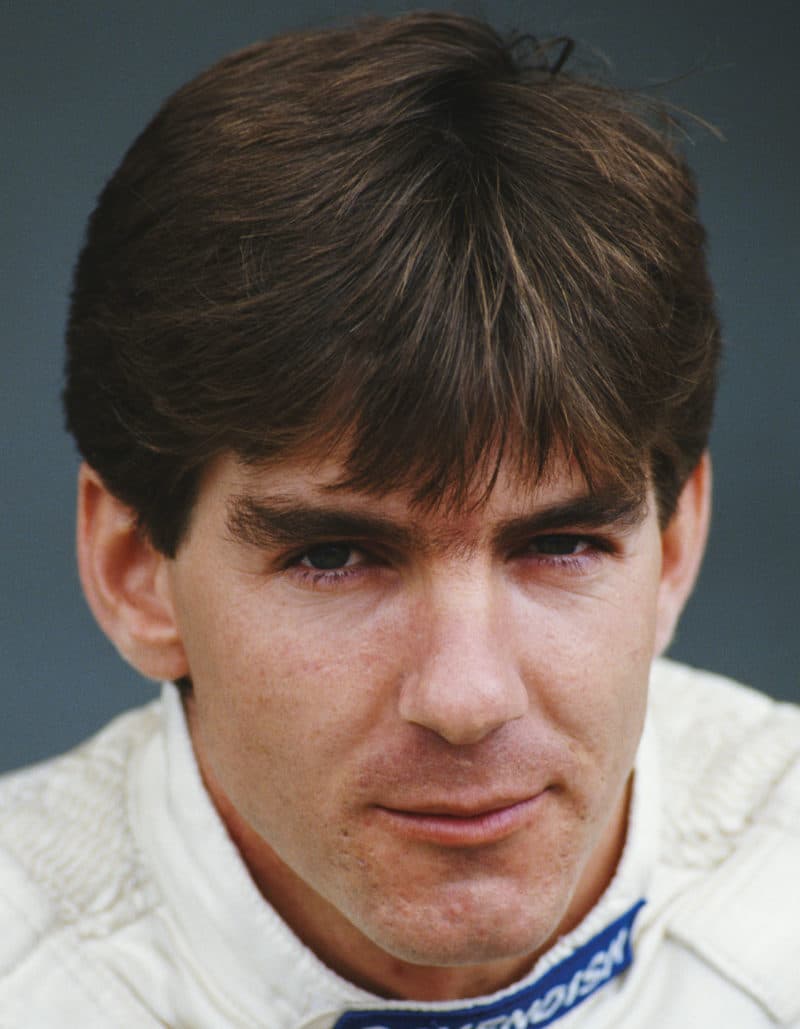

A young Julian Bailey ready to battle his way up the racing ladder

Getty Images

Stepson Jack Clarke made a decent stab of the racing driver life himself, rising as high as Formula 2 and winning a round in 2011 at Brands Hatch – Julian’s favourite old stomping ground – before running out of steam after a BTCC season in 2014. Now Jack, 33, and his younger brother Daniel Bailey, who sensibly studied hard and initially headed for the City rather than Brands after graduating with first class honours in Spanish from Bristol University, run thriving esports business Veloce Racing, which has just diversified into the ‘real world’ as a team entrant in the W Series all-female single-seater series and the new Extreme E initiative. Veloce’s Stéphane Sarrazin and Jamie Chadwick, the W Series champion Clarke also co-manages, had a tough start to their Extreme E adventure in the Al’Ula desert of Saudi Arabia back in March when Sarrazin rolled out of qualifying. But as the brothers have learnt from Julian, racing is all about overcoming adversity…

In the aftermath of the Saudi Arabia (mis)adventure, Motor Sport met Bailey and sons to re-tread some of what made Julian’s career so eventful and find out how his natural instinct to hustle, then grab chances when they came, have fed directly into the DNA of Veloce. Inevitably we gathered in a pub garden, The Running Mare in Cobham, Surrey, a popular motor racing watering hole run by Julian’s brother, Adrian. Bailey has always lived hard and it’s caught up with him. At 59, he’s endured serious health problems in the past year – but that didn’t stop a steady flow of scotch and Cokes as we talked. He can’t have been easy to live with at times, but Jack and Daniel’s obvious affection and warmth for the man they call ‘Jules’ rather than Dad speaks volumes. This is a proper racing family, with a modern twist.

Motor Sport: Your Rat Pack generation were all hustlers, weren’t they?

Julian Bailey: “Everyone was. It was a case of dog eat dog really. If someone had a sponsor you’d try and nick it. I had Cavendish Finance [in Formula 3000] that started to appear on Perry McCarthy’s car. I couldn’t stop it, everyone had their own agenda. But I didn’t mind. All fair in love and war.”

At one point did you know you had the hustle gene?

JB: “From day one, when I started to get into Formula Ford. It wasn’t a case of what can I do, how can I get there? I thought that’s what I’ll do, and that was it. Everyone was different then. It was hard but somehow we managed, whereas I don’t understand what Dan and Jack do. All this esports…”

What do you make of that?

JB: “I wish I could do it, that I was one of these highly paid drivers. It’s amazing they can get blokes all round the world that earn the money they do. You couldn’t make a living out of Formula Ford. Hats off to them; I just wish I understood it more.”

British F1 champ ‘Wall of Fame’ now has a space for Lando Norris…

Andrew Ferraro

Damon Hill and Johnny Herbert told us recently that you guys had more fun back in the 1980s than drivers do today. Would you agree with that?

JB: “Possibly, I don’t really know what goes on now. But you see all these polished professionals who are politically correct. In our day you said whatever came out of your mouth. You could get away with more.”

Was there a camaraderie or was it rivalry?

JB: “Rivalry really. From my point of view it was. Now we’ve become friends and we can joke about that. But we always had an eye on each other: what are they doing? We were always looking for an advantage.”

You lived with adversity from the start. In 1980 you busted yourself up badly in a Formula Ford crash, didn’t you?

JB: “Seven bones I broke. I came back faster, although not fitter obviously. Straight away when I tested at Snetterton, where it had happened, I was quicker by a long way. I couldn’t understand it myself. If you overcome something like that… I was living in Spain, I had no money and thought, ‘You’ve got to give it a go and finish what you started.’ I couldn’t hold the wheel for more than two laps because my arm was as thin as a rake. But I ended up getting the lap record in both FF1600 and FF2000 after that accident. Remember the old Russell? One hell of a corner –a widow-maker.”

The 1987 F3000 season brought Bailey some decent outings in Pergusa and the Bugatti Circuit, Le Mans (where the photo, right, was taken), crowned with a win at Brands Hatch –a favourite track

You had a huge rivalry with Mauricio Gugelmin, who came over from Brazil with money. What was that like?

JB: “It was intense. But I always felt I had the upper hand, that I was better. The fact I lost the [1982] RAC championship was because he took me out, no two ways about it. I could see him coming and bang, straight off the track. I got my own back by winning the Festival when he put himself off. It was nothing to do with me, he just turned in and went over my wheel. My wheel was bent and so deformed but I held on for two laps in the lead. I thought it was bound to break, but I won. He bit his tongue. Just desserts.”

Have you seen him since?

JB: “Yeah. He didn’t mention it.”

Jack Clarke: “We had a barbecue at Gil’s and he invited Mauricio over. It must have been 20 years since they’d seen each other. Jules [Julian] had got a lot smaller and Mauricio had got a lot bigger!”

JB: “Perry would say he’d pulled the rip cord – he looked like he’d blown up… Remember, his best friend was Ayrton Senna and they lived together, so I got to know him really well. He was a bit of hero in our eyes.”

We have a memory of watching you in your black BP-sponsored Reynard FF2000. It was at Druids at Brands, you were miles out in front and you took an extreme wide line into the corner, lap after lap – to the centimetre.

Daniel Bailey: “Whenever Jack raced at Brands Hatch there was always a lot of talk on different lines.”

JC: “Paddock Hill Bend was the one I most remember. We used to sit and watch old videos of Jules going through there. I put a lot of the success I had at Brands down to that.”

“Remember the old Russell? One hell of a corner –a widow-maker” Julian Bailey

DB: “If you look at Jack’s Formula 2 race win there, he came through from third to take the lead into the first corner, just as Julian did in F3000. It was a carbon copy move.”

JB: “The only difference is you hit the car in front of you and I didn’t…”

JC: “There was a slight brush of wheels. I got away with it, just about.”

What was it like growing up with Julian?

JB: “I’d finished all my racing by then.”

JC: “Well I remember the Lister days really well and you and Jamie Campbell-Walter were always winning [Bailey won the British GT1 title with Campbell-Walter in 1999, then conquered the FIA GT Championship the following year]. It was exciting to watch.”

Julian in the 2001 GT championship driving a 7-litre Lister Storm

THIERRY DELAUNAY / DPPI

DB: “My first race action was when I was in the womb – at the back of a garage in 1991. He lit up an engine and apparently I kicked. But my real memories are of that Lister era when he and Jamie Campbell-Walter tended to stick it on pole and win. When they won the championship I was on a school trip and missed it! Then there was the MG Le Mans campaign with Kevin McGarrity and Mark Blundell [in 2002]. Now that looked like fun.”

JB: “It was because we knew we’d never win with that MG-Lola. The engine package was a disastrous decision [it ran with an AER 2-litre turbocharged inline four to qualify for the LMP675 prototype class], although the car itself was good. We didn’t take it that seriously because we knew we had no chance. Mark and I, we still had that old rivalry between us. With the Nissan Group C car [in 1989 and ’90, again shared with Blundell] we knew we had a chance of winning. When I look back I regret not appreciating how good it was.”

Jack and Dan, what has Julian taught you?

JC: “How to mow a lawn in a straight line.”

DB: “I was the one mowing the lawn! I was quite proud of my skills actually.”

JC: “He was critical in an appropriate way. When you are head in hands, for me whether it was failing exams or spinning out of a race, the person you wanted to see was Jules because he’d been there and understood how to peptalk. He was critical but fair.”

DB: “With someone who came up against the odds like Julian, you learn there are no barriers to what you can achieve. With Jack, if we couldn’t find sponsorship for the next year we’d still find a way. From the start of Julian’s life to getting into F1 there were barriers he had to get over: coming from a council house in Woolwich, then living in Spain [his parents ran a supermarket] and coming back. We were all brought up to take it one barrier at a time.”

JB: “One at a time. You get there in the end.”

MG-Lola EX257 at Le Mans in 2002 and a fifth DNF

DPPI

JC: “The good times when they roll make it worth it. But the bad times… not just when I was driving, Julian has always been a good example, the master of adversity. When I won a race he was not really around when everyone was popping champagne – well, he was still popping champagne, but on his own! The moments of adversity were where the nuances of his life and career were more powerful and that translates to where we are now. But this is such a feast and famine game.”

JB: “You have to appreciate the good times because the ups are few and far between. When you’ve won a race you feel wonderful, everything is beautiful and easy. But how many times does that happen?”

DB: “Saudi Arabia and the first Extreme E race was the first time I experienced that. I wasn’t driving the car but obviously I was heavily invested. Like Julian had to as a young driver, we raised the finance to start Veloce Racing and we had deals committed here, there and everywhere that then fell through. One day we had the finance, the next we didn’t. Then you make it, but have a crash on the Saturday and don’t even get to race on the Sunday – and we’d been in Saudia Arabia for 10 days because of the quarantine time. It was gutting.”

JB: “That brought you back down to earth with a bump, didn’t it?”

Julian has made five Le Mans appearances, including 1990 in a Nissan R90CK, leading.

Getty Images

DB: “It made me realise that while Extreme E is innovative, at its core it’s still a racing series. In the virtual esports world things are a bit more robust…”

JC: “It’s a lot cheaper when you crash! The sentiment carries through. I stopped racing after 2014 when I did the BTCC. I was all right, but all right doesn’t really cut it and there’s no better person than Julian to say it. But as Dan says, we love the sport and we’re sort of addicted to its adversity. When I gave up I came together with Rupert Svendsen-Cook, who is now along with Dan, myself and Jamie MacLaurin co-founder of Veloce. Those Jules stories I now tell in a beer garden on a Friday night are a perfect reference to how we run our business. You have those highs and lows, and those moments when you look like an idiot. Every racing driver has that. Those stories make up the DNA of Veloce. When I was racing, we managed to clear out mum and Jules two races in… so we had to raise the cash race by race, selling stickers on a car, and then you’re looking out on a cool-down lap at somewhere like Castle Combe, and there are two men and a dog – and you’ve got to make that work. You have to be creative.”

How big is the esports market?

JC: “We have 60 to 90 gamers under management and last month we hit 215 million views across 40 channels. For us it’s the same hustle you need for a junior formula category, but if you say Formula Ford to someone, they’re probably not going to know what you are talking about. Esports is a gateway to much greater accessibility.”

Veloce has moved into the world of real racing via Formula E – but crashed of its first event in Saudi Arabia

Extreme E

DB: “You want to apply that hustle and actually get some more long-term reward, which is where esports came in and now Extreme E. We had to find a growth sector where what we know is applicable to the modern world. In Extreme E we can see a series that is born out of where we think the world is going: awareness of climate change, gender equality, the future of the automotive industry.”

“Appreciate the good times; the ups are few and far between” Julian Bailey

JC: “The game changes but the players don’t. Jules says he doesn’t understand it, but at the end of the day it’s the same thing. Everyone is competing and it still takes blood, sweat and tears to get to the start line, and more often than not tears afterwards, too. There’s so much romance around the good old days and the Rat Pack. But the characters were cool and the stories are amazing. Jules, tell the story about the wing mirrors that fell off.”

A formal launch for the Tyrrell 017 in 1988, with Julian, left, and Jonathan Palmer dressed for the occasion

Grand Prix Photo

JB: That was on the Tyrrell in Rio for my first grand prix [in ’88]. It was my first time in the car. In the hour and a half practice session, I wanted to get going, but for the first and only time in my career the steering wheel wouldn’t go on and they had to change the rack. Being Tyrrell, it took a while to find one. I finally got out with half an hour to go. I went out on the circuit and I didn’t know which way to go. I walked the circuit but only once because the heat was horrendous. All these people were coming past me and one wing mirror was down there, the other stuck up in the other direction. I came in the pits and said, ‘Ken, I can’t see behind me.’ He said, ‘Can you see in front of you? You should be looking ahead.’ Nice bloke. I nearly took out every driver. Afterwards there was a queue of them – Senna, Mansell, Piquet – lined up to tell Ken I was terrible. Ken was very sympathetic. He said to Piquet, ‘I remember when you started you were a w****r as well.’ Thanks, Ken.”

Jack, right, in 2014 – his final year racing – with would-be GP2 champion Jolyon Palmer.

Getty Images

How did you get on with Ken?

JB: “I found him a very difficult person. Autocratic. That’s why he survived in the business; he wrote the cheques. His wife Norah did the catering: the option was a ham sandwich or ham and tomato. That was it. I had better catering from F3000 teams. He said it as it was, which is how he survived. I admired him, but I didn’t actually like him or get on with him.”

DB: “Was that the time in Brazil when Ronnie Biggs ended up in your hotel room?”

JB: “No, that was with Benetton [in 1989]. I was out there to get in the car if Johnny Herbert couldn’t [for his debut when Herbert was still recovering from the terrible leg injuries he sustained in an F3000 crash at Brands Hatch]. Once Johnny got through qualifying and I knew I wouldn’t be racing, we went out that night. We met Ronnie Biggs in a club and he ended up back at my hotel. He started to fall asleep on a sofa and there was security all around him saying, ‘You’ve got to move, sir.’ So I got him up, took him to my room and said, ‘Have a shower, you’ll be right as rain.’ He got in the shower, then fell over and pulled the shower curtain down. I couldn’t open the door because he was behind it. Then the phone rang and it was Adrian, my brother. I said: ‘You’ll never guess who’s in my shower…’ There was water all over the floor. Eventually I got him up, I don’t know how. Good job Johnny Herbert didn’t fall over that night, although I would have liked to have finished fourth like he did.”

A first – and only – F1 World Championship point arrived for Julian driving for Lotus at the 1991 San Marino GP

Getty Images

Your best was sixth at Imola for Lotus in 1991. Was that a good moment?

JB: “It wasn’t great really because I could easily have finished fifth, if not fourth. I spun, I came into the pits, my gearbox kept jamming. I was quick at Imola, much more than at Monaco [he failed to qualify around the principality and by the next race in Canada he’d been replaced by Herbert. When Bailey landed the drive at Lotus, he recalls being handed a set of overalls with Herbert’s name on the belt].”

Why is it that you never got your head around Monaco?

JB: “I don’t know. It’s a cognitive thing really. Macau, I loved it, but Monaco… it’s a class thing, I suppose. I never really believed I belonged there. At Macau I did because it was a s***hole.”

You’ve always been very honest about your career. Do you have regrets?

JB: “Yeah, obviously. To borrow a great line from a film, I felt like I could have been a contender, but I never was. I don’t know why. I never had the material around me to make it. Sometimes I’d look at Mika Häkkinen [his team-mate at Lotus] and think you lucky b*****d. I wish I could have been like I was in FF1600 or FF2000. I was at my best then. I felt I could have beaten Ayrton Senna in those cars. That’s what I regret.”

The Bailey-Clarke wall of fame at The Running Mare

Andrew Ferraro

By the time you got to Lister you were very assured, unlike earlier in your career.

JB: “Certainly in F1 I didn’t feel confident. Just the fact I didn’t have the materials. At Imola I remember Roberto Moreno coming past me in that Benetton-Ford and he was miles an hour quicker than me in a straight line. How can you compete with that?”

But you knew you had the ability?

JB: “Yeah, I think I did. But I knew I was never going to get in one of those cars.”

What have you guys taken from that?

DB: “We’ve been lucky to get a lot of that grit. We’ve also been lucky to have a nice childhood and education, then combine that with a strategy and mental aptitude and we’ve been in a really good place to take a lot of the best from Julian’s career and apply it. And I think that’s what it is: application.”

Even better than the real thing? A sim racing scene showing driver Baptiste Beauvois of Veloce eSports (piloting the Lexus) during the 2020 FIA Gran Turismo World Tour.

Getty Images

Where are you trying to go with Veloce?

JC: “We have this amazing esports business that is its own ecosystem. We work with Mercedes, McLaren, Alfa Romeo, with Lando Norris, we even have a team with [boxer] Manny Pacquiao now. We’ve established ourselves and the reach we have is global, just three and a half years since we founded that side of the business. At the same time, myself and Rupert manage Jamie Chadwick, one of the fastest female racing drivers in the world, and we’re in what we believe to be an incredibly pioneering series in Extreme E.

Where are the opportunities today? A young Julian Bailey in 2021 would say in electric vehicles, females racing and esports. Where can we go? We want to just keep going. There’s a lot of electric motor sport on the horizon. We want to maintain the position we have in esports. For me it’s come off the back of what Jules would say was an unsuccessful racing career. I was good on my day, but ultimately not good enough. Now the fan in me is really proud we have Adrian Newey on board [as ‘lead visionary’], double Formula E champion Jean-Éric Vergne as an investor. Veloce can go anywhere. We’ve got the confidence that maybe Jules lacked in the past.”

Esports – a mystery to Julian but a thriving scene

Julian, what do you think of what these guys are doing?

JB: “Good luck to them. I don’t understand it, I wish I did. Because I’d be good!”

You must be proud of them.

JB: “I am, very proud. I just hope they don’t crash first time out at the next race.”

JC: “Look under his jacket – he’s wearing a Veloce shirt. He’s more committed than he lets on, even if he doesn’t understand it.”