Uncovering the lost genius of 'Uncle' Carlo Chiti

Hot tempered yet kindly, determined yet soft-hearted, opinionated but a natural team builder. Enzo Ferrari thought him vainglorious, but Carlo Chiti had much to be truly proud of. Paul Fearnley portrays a design and engineering genius whose reputation took years to recover from one misstep

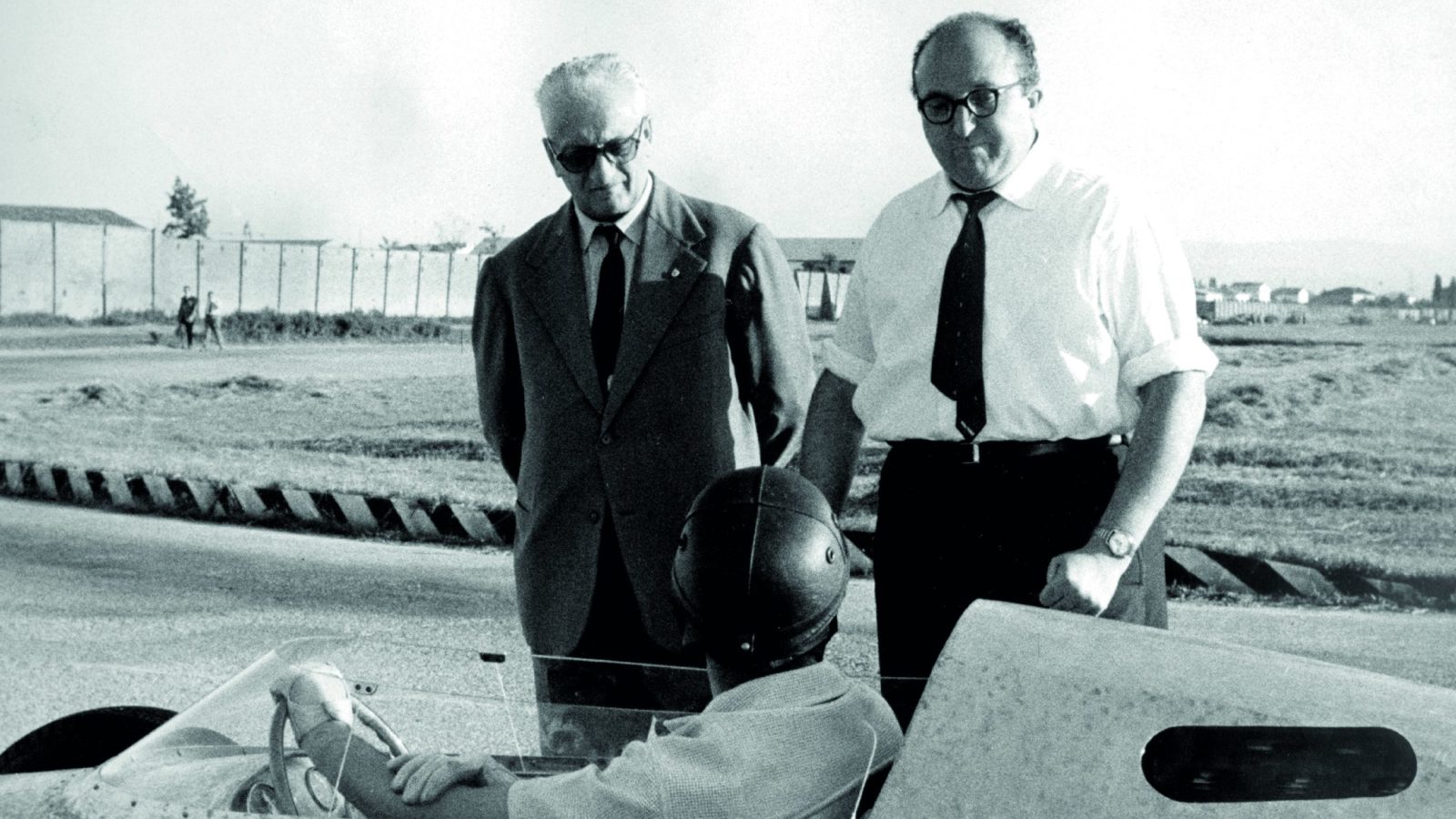

Modena, May 1960: designer Carlo Chiti in conversation with test driver Martino Severi; Enzo is listening

Getty Images

Bespectacled, portly and soberly overdressed –raincoat (often even come shine) and a penchant for Borsalino hats, business suit, cardigan/pullover/tanktop, collar and tie – he was instantly recognisable at Scuderia Ferrari. Yet Carlo Chiti has largely become a forgotten figure despite his many achievements during a short but fecund spell at Maranello and later, and for very much longer, at Alfa Romeo via Autodelta. We’ll gloss over his disastrous ATS interlude for now.

He joined Ferrari from Alfa as replacement chief engineer for friend and fellow Tuscan Andrea Fraschetti – killed testing an F2 Dino at Modena in 1957 – and thus was at the helm when Mike Hawthorn became Britain’s first Formula 1 world champion. Before Phil Hill could become America’s first three years later, Chiti, having overseen the final championship grand prix win for a front-engined car, achieved the seemingly impossible: he coaxed Enzo into ‘putting the horse behind the cart’. His subsequent rear-engined ‘Sharknose’ designs put Ferrari firmly, albeit briefly, back on top in F1 and assured its sports-racing hegemony – bolstered already by Chiti’s front-engined Testa Rossa iterations – until long after his summary exit.

For he was among eight key staff whom in November 1961 united to complain about pay and conditions – and Enzo’s wife. Stirred by son Alfredino’s death in 1956 and her husband’s infidelities, Laura had been taking a keener interest in the company, as was a principal stockholder’s wont. Acting as her chauffeur/guardian at races did not sit well with Chiti, while Laura’s lack of diplomacy made for an easy target in a macho world. Her slapping commercial manager Girolamo Gardini was the trigger for the walkout. Some of Enzo’s renegade ‘generals’ trailed back after a month or so, quietly re-pledging allegiance. Opinionated and voluble, cultured and erudite, Chiti was not among them. Enzo blamed external causes for that – but not before letting slip this about Chiti in his 1962 book My Terrible Joys: “A man of vast theoretical knowledge equalled only by his eagerness to win a reputation for himself.” Two bulls in a field.

Though Chiti would eventually be roundly upstaged by his successor Mauro Forghieri, he had laid down vital groundwork: installing a small wind tunnel at Maranello; a belated acceptance of disc brakes and fibreglass; and a low polar moment that pre-dated Forghieri’s Trasversale gearbox by 13 years. The engine, tending towards simplification under Chiti, was no longer undisputed king. According to the ruminative Phil Hill, this “more holistic approach” meant that the F1 Sharknose had been “built the way a racing car ought to be”; he would join Chiti at ATS for 1963.

TZ models were Autodelta’s flagships but more humble GTAs brought the prizes

Getty Images

Chiti oversees early 156 testing at Modena in 1961. Enzo watches while Forghieri makes notes

Getty Images

The latter project was too soon shorn of the financial impetus promised by Count Volpi of Serenissima and became a motor racing byword for laughable incompetence. So bad was it that Chiti would spend 16 years restoring his F1 reputation through Alfa Romeo GTs, saloons and sports-prototypes, and as an engine supplier to McLaren, March and – to much greater effect – Brabham.

“Chiti never criticised Enzo Ferrari,” says Andrea de Adamich, who drove with aplomb all of the above bar the Brabham. “He always spoke well of him. Though he never spoke of his past successes.”

Maybe so, and yet…“I think it was always Chiti’s aim to return to F1, to beat Ferrari,” says Bruno Giacomelli, the lone driver upon Alfa’s long-awaited return to grands prix. “He never said anything about it but, believe me, it was what he’d had in mind since the day he left.

“It was only because of Chiti that Alfa did F1. No Chiti, no way! There was always a fight against Alfa Romeo. They had won world titles with Farina and Fangio, and for sure they didn’t like Autodelta. Plus Alfa was a state-owned firm losing 200 billion lire a year.

“So we had to enter F1 softly, without too much glamour. We didn’t even have a proper truck. They put us at the end of the pit lane [at Zolder in 1979], with no garage for our materials. And we showed up with an old car. We did only five races that season.”

Born in Pistoia in December 1924, Chiti earned an aeronautical engineering degree at Pisa University – he also studied chemistry – and joined Alfa Romeo’s Experimental Department. Early excitement, including the 6C 3000CM that Fangio drove to second place in the 1953 Mille Miglia, faded quickly as the Milanese company throttled back. Thus he arrived at Ferrari brimming with ideas corked by frustration. There, however, he would fall between two stools being neither old school nor a young thruster as a burgeoning company was incorporated.

HIS SECOND SPELL WITH ALFA was necessarily a steady burn after ATS. Captain of a ship buffeted from without, he did his utmost to shield and encourage those within an unlovely walled compound that evoked a correctional facility and harboured organised chaos and innovative endeavour in roughly equal measures. This process involved his tempering a volcanic temper – the revolver kept in a drawer was sometimes fired in frustration at the office ceiling – via a big heart and a soft touch for small stray dogs, be they three-legged or one-eyed, which he rescued and sheltered at the factory.

“During practice at a Buenos Aires 1000km a dog crossed the circuit in front of the pits,” says de Adamich. “Chiti was fat but fantastically agile when needed; he ran onto the circuit to save it. And one of the dogsat Autodelta would immediately arrive, protected by Chiti, whenever it heard money in the coffee machine; it wanted the sugar.

“Ferrari was more professional,” continues de Adamich, whose single-seater ambitions took him to Maranello from 1968-69. “But not so relaxing. No human relations; Enzo never spoke with his mechanics. But Chiti was a fantastic human being. Autodelta was his family and he ‘lived’ in the workshop. Only Bruce McLaren was like him in racing. He was everywhere. He had complete responsibility. Engineers like him don’t exist today because everybody specialises. He did everything, like Forghieri at Ferrari, but it was harder to have a relationship with Mauro. Of course, they were not perfect in all capacities; they were a little bit overlooking everything.”

Nascent Auto-Delta, founded jointly with Alfa dealer Ludovico Chizzola in Udine and registered in March 1963, was first intended to make existing products more competitive for others. Before the end of 1964, however, it had been drawn to Alfa’s bosom – and lost the hyphen in the process – at the farming hamlet of Settimo Milanese. Empowered to get a once sporting marque racing (and rallying) again as its official competitions department – prototypes, engines, team – it would perform the role the Scuderia Ferrari had in the 1930s: to enable Alfa either to bask in glory or deflect defeat.

Chiti watches Ferrari mechanics work on the 156s. He oversaw every aspect of his cars from drawing board to pitlane, especially once he moved to Alfa and Autodelta

Getty Images

The beautiful and successful TZ2 of 1965 was its first standalone, but it was the neat and nifty wheel-waving GTA that truly brought home the bacon: nine ETCC titles – four drivers’ and five manufacturers’ – from 1966-72 that make it arguably the greatest touring car. The sports-prototypes were not so fruitful, the elegant T33/2 generally lacking the speed and reliability of rival Porsche. The eventual breakthrough came in 1971 with the 3-litre V8 T33/3 monocoque: Alfa Romeo’s first world championship race victory for 20 years.

“We were beating Porsche 917s driven by Siffert and Rodríguez when a circuit was slippery,” says de Adamich, who scored that Brands Hatch win alongside Henri Pescarolo. “I had returned because [Giuseppe] Luraghi, president of Alfa Romeo, had promised me a V8 for an F1 project: with McLaren [in 1970], it was 100% me; with March [in 1971], Chiti directed. The McLaren car was fantastic to drive. Unfortunately, the engine was uncompetitive. The other problem was the McLaren engineer who came to Autodelta and made suggestions about its prototype. Chiti didn’t like this and started talking with March. They needed money and free engines, so were not criticising.”

“He had a volcanic temper – and a soft touch for small stray dogs”

The flat-12, promised but never delivered to March, that followed was clearly a direct challenge to Ferrari, although it being routinely swept aside by V12 Matras in the 1974 World Championship for Makes proved that more work was needed.“We reckoned that Ferrari’s flat-12 had a good 30-40bhp more than a Cosworth DFV,” says Brabham designer Gordon Murray. “As a percentage, that was huge in the 1970s, and we felt we needed a ‘12’ to remain competitive: Porsche wanted quite a bit of money for theirs; Autodelta’s, I believe, was free.”

As a result of this deal, Alfa’s 1975 sportscar programme, bar its second Targa Florio win since 1971, was farmed out to Willi Kauhsen’s Cologne-based team. That it won seven of nine rounds to secure the World Championship for Makes was a backhanded compliment.

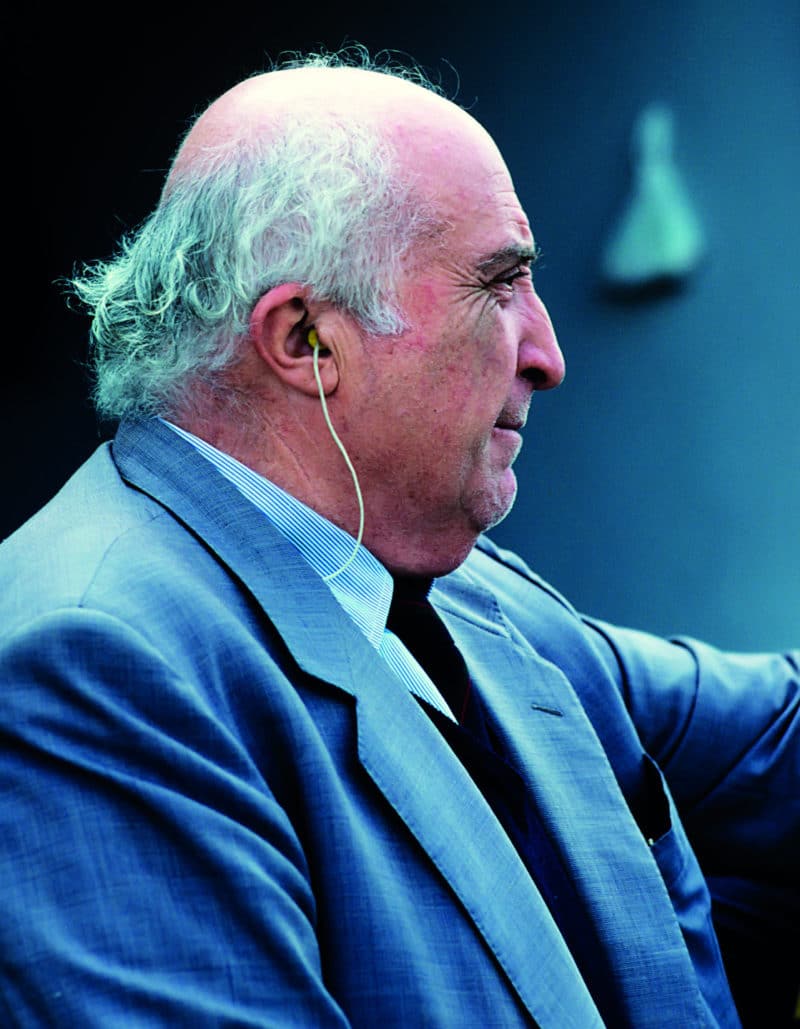

Again the collar and tie: Chiti in repose

Getty Images

All smiles with Bernie after Brabham fan car’s debut win

Grand Prix Photo

favoured ‘son’ Giacomelli set pole at ’80 US GP

Getty Images

In 1975 the 33TT12 finally took the sports car Makes title, winning seven of eight rounds

DPPI

Brabham foray – Murray and Lauda with Chit

Grand Prix Photo

“We didn’t win races; we absorbed them,” says Derek Bell, scorer of three of those wins alongside Pescarolo. “The Alfa was a bloody good car. Sounded wonderful. But the [turbocharged] Alpine-Renault should have won all the time. We used to go like hell and hoped they would fall out. They did. “I never saw anyone from the factory – Chiti was never there – and as far as I know the cars stayed at Willi’s. I am sure that Autodelta was doing a wonderful job rebuilding engines and getting them to us, that it was a more cohesive relationship than we imagined, but it was a German operation in my opinion.”

Autodelta’s hands-on relationship with Brabham in contrast would suffer a sticky start.“Had I developed BT44B and stayed with Cosworth we could have had a much more competitive 1976-77,” says Murray. “The bad side of Autodelta was that they couldn’t control themselves. They tried different stuff all of the time and I didn’t know about all the changes.”

When finally it was persuaded to provide a base-spec engine for 1977, Autodelta called it Tiger. Its development was Super Tiger.

“I should have won twice that season,” says John Watson, whose BT45B came within half a lap and a cup of fuel of victory in the French GP at Dijon-Prenois. “The engine looked fantastic. Had it been around in the early 1970s, when it would have been more appropriate, it probably would have won lots of GPs.”

Murray: “Slowly we made it lighter, more reliable, less thirsty and we were pretty competitive by 1978.” Niki Lauda scored two wins as Chiti came within five points of beating Ferrari in a constructors’ battle. “But ground effect had turned up and the engine was the wrong shape. So Autodelta built us a V12for 1979, in about three months. They were excellent when a quick reaction was needed. “It had been the same with the Fan Car [in 1978]. We had about two-and-a-half months to conceive, design, build and test it before the Swedish GP, and Autodelta went into overdrive. That it was successful vindicated our sticking our necks out, and Chiti was as disappointed as I was when [team boss] Bernie [Ecclestone] asked us to withdraw the car under pressure from the other constructors.”

“You needed people like him for leadership and decision-making”

That rushed V12 for 1979 proved unreliable; Brabham was using a Cosworth before season’s end. The supposedly hard-nosed Lauda walked away. Though he had sensed its winning potential, a V8 felt boring after a 12.

On the wane: despite past glories, Chiti’s Motori Moderni projects struggled. Here at Brands in ’85 he muses on how to boost Minardi’s performance

Alamy

Murray, to a lesser degree, was conflicted, too: “There was a lot of mutual respect. Those old boys of the 1960s and 1970s had so much experience that instinctively they knew what to do, what was right, what was wrong. Chiti was a genius in his own way. You needed people like him when teams were small, for leadership and decision-making.

“He was a good sport, too. Once, he took us all out for dinner and there I did my trick whereby I run my hand slowly through a flame without burning myself. Chiti picked up the candle on the table in front of him, stuck it in his mouth and kept it there for 10 seconds or so. When he took it out it was still alight.”

Watson: “He was like a character from a Fellini film: a big man by then, those glasses, sweat pouring off him. He had a penchant for wearing a knotted handkerchief when it got hot, and would put his feet in a bucket if he was really overheating. But there was a great aura about him. His reputation was considerable and I respect people like that.”

Many of Chiti’s legion of drivers called him ‘Uncle’, and he formed very strong bonds with the likes of Richie Ginther, Lucien Bianchi and Teodoro Zeccoli, whose feedback he trusted. “He could be very tough,” says Giacomelli. “He had a temper: Toscanaccio. It means many things Tuscan – a strong character, but easy to wind up. But we respected each other. I read in an interview [with Chiti’s medical professor son Arturo] that I had been like a son to him. He never told me that! But it was one of the best days of his life when I qualified on pole at Watkins Glen [the final GP of 1980]. At dinner that night the atmosphere was fantastic. We were right up there, at the end of our first full season.”

New recruit Patrick Depailler had predicted that Alfa the constructor would win a grand prix in its first full year back – and it almost came true.

Giacomelli: “We had lost Patrick [in a Hockenheim testing crash] two months before and the responsibility was on my shoulders. Alfa and Chiti supported me. Watkins Glen was supposed to be a coronation of all the hard work we had done. I was leading, not relaxed but comfortable: fantastic grip, fantastic balance, using 500rpm less yet getting quicker. Then we had a failure that we’d suffered a couple of times before: an ignition coil.

Gachot in his Coloni confirmsthe Subaru flat-12 is no winner

PAUL-HENRI CAHIER/GETTY IMAGES

“I had already tested the car for 1981 and set a new record at Alfa’s Balocco test track. The prospects were good. I signed for two years. Then skirts were banned and Goodyear retired and we had to start over. For half that season we ran 6cm above the road while other teams invented systems to lift and drop their cars. Chiti said, ‘We cannot cheat like that. We are a big company with a reputation.’ “Then Gérard Ducarouge arrived – I think it was Chiti’s decision to hire him, but then they fought – and he modified the car. It was fantastic by the end of the season. Again.” Third at the Las Vegas finale was so nearly second and might have been a win but for a half-spin and a struggle seeking reverse. “Then they changed the regulations again: to flat bottoms.”

Ducarouge’s carbon-fibre 182 showed early promise in 1982 – de Cesaris set pole at Long Beach and ran out of fuel in sight of victory at Monaco – but Alfa would officially withdraw. It was a reshuffle: Paolo Pavanello’s Euroracing was handed responsibility for the F1 cars from 1983, Chiti was put in charge of engine design – a demotion no matter how you dressed it.

He had, however, been experimenting with twin turbos as long ago as 1977, when T33SC won all eight rounds of a lacklustre World Sportscar Championship. Alfa’s 1.5-litre V8 thus equipped for 1983, de Cesaris would lead and set fastest lap at Spa before retiring from second, and finish second at Hockenheim and at the Kyalami finale – but an increasingly isolated and embittered Chiti was on his way out, to establish Motori Moderni in Novara. While Euroracing was scoring a big fat zero in 1985 – leading to total retreat from F1 by cash-strapped Alfa – newcomer Minardi was striving with Chiti’s V6 turbo for three seasons without troubling the scorers.

Chiti’s final F1 venture sadly smacked of ATS: the much-derided 3.5-litre flat-12 for the Coloni Subaru debacle of 1990. He died of a heart attack in July 1994.“We had three full seasons,” says Giacomelli. “We needed five at least. What we did in the circumstances was fantastic. And our best car was the 179 of 1980, built and developed under Chiti’s direction. Italians thought him eccentric, too, but, believe me, he was very clever, cleverer than people thought. Sadly his intelligence wasn’t used in the best way it could have been.