Notice to Club Secretaries

Club Secretaries are specially invited to send the Editor aragraphs about the activities of their clubs, and, in particular, notice of forthcoming events. All reports of competitions, meetings and other…

The coronavirus crisis has forced Formula 1 to take a long, hard look at itself and find the answers to some very searching questions – or at the very least accept that those questions need answers.

As the sport’s activities dried up in the early part of the year, and factories were closed for months at a time, the potentially existential nature of the threat became clear to many of those involved in the sport. Global lockdowns and the postponement or cancellation of 10 races shattered any complacency. A number of far-reaching decisions were made in an attempt to shield F1 from the clear and present dangers – as well as those that might well be posed in a likely future where the immediate threat from the virus has receded, but the devastation wrought by its economic consequences becomes the new concern.

Over the next decade, F1 has to ride out the expected global recession caused by the virus, on top of the issues that were already there before COVID-19 changed the world. Chiefly, how to stay relevant and prominent as a new generation with different priorities influences global direction. How will – and should – the cars be powered as the world moves deeper into a century that will inevitably be dominated by the climate crisis? Who will be running the teams? What will the cars be like? Where will the money come from? Many questions face F1 as it emerges uncertainly into a changed world this year, this decade and beyond.

The coronavirus crisis forced F1 to accelerate down a path upon which it had already set its course – to drive down costs and make the sport more sustainable.

What was originally regulated last October as a budget cap of $175m a year, with major exemptions for areas such as the salaries of drivers and top executives, engines, marketing and more, has now after months of talks settled at an initial $145m next year, descending to $135m for 2023-25.

That is expected to make a big difference to what is perceived to be another key requirement for F1’s future success – increased on-track competitiveness.

A more stringent set of rules should make it harder for the best-resourced teams to develop cars with a massive performance advantage over their rivals, there has been an attempt to enshrine a way of balancing performance into the rules, and limits on costs will reduce the disparity in budgets.

Liberty Media and the FIA are grappling with F1’s future

PA

While in recent years the likes of Ferrari, Mercedes and Red Bull are spending double or even, in some cases, triple the amount of those further down the grid, that will no longer be possible – the numbers will be more like 30-50 per cent more at most. It remains to be seen what effect the expected impact on global finances from coronavirus will have on F1, but the shockwaves are already being felt.

Williams, one of the sport’s most prestigious names, is up for sale, a situation that has been created by its poor performance over the past two seasons, but from which recovery has been made a whole lot tougher as a result of coronavirus. And the upheaval around the world created by the pandemic has led to inevitable questions about whether the car manufacturers in the sport, which not only account for three of the teams but also supply engines to all of them, can justify continued involvement.

On that front, there have been reassuring signs recently. Mercedes F1 boss Toto Wolff made it clear parent company Daimler sees F1 as a “core activity” and that it is “in it for the long term”. And Renault, whose involvement in F1 had been part of a review of all corporate activities following the financial scandal surrounding former boss Carlos Ghosn, has said it too is in F1 to stay. Of Formula 1’s four manufacturers, that apparently leaves only Honda with questions surrounding its involvement for the next few years, arising from its decision last autumn to extend its contract with Red Bull only by one year until 2021.

The sustainability – or otherwise – of the sport extends into areas far beyond finances.

The coronavirus has been an unexpected and serious crisis, but it will presumably eventually subside. And then attention will turn back towards another potential threat – global heating.

With global warming high on the agenda, will burning fossil fuels still be relevant in future years?

Getty

Had it not been for the coronavirus, it’s possible that the defining political discussion around the start of the F1 season might have been the optics of flying to Australia to drive cars around in circles for three days in the shadow of the climate change-driven bushfires that devastated large swathes of the country in the preceding months.

No-one in leadership circles in F1 is blind to the threat that the climate crisis poses to the sport, and all accept that the sport has to move into the future by embracing its responsibilities in this area.

FIA president Jean Todt identifies the environment as one of the two ways in which the future of motorsport could be at risk – the other being some form of monumental crash that involves the deaths of members of the public, such as the 1955 Le Mans disaster. By extension, reinforcing F1’s responsibilities towards greenhouse-gas emissions is key. The sport has already pledged to become carbon neutral by 2030; attention now turns to how the engines will look under the new formula to be introduced in 2026.

Fuel manufacturers are busy developing the new generation of ‘e-fuels’, which will essentially be carbon neutral

Getty

“It will be up to the new generation to demonstrate whether or not it’s still relevant to race in cars and go around in circles around the world,” says Renault F1 managing director Cyril Abiteboul. “But more than that it’s important that F1 remains at the edge of what technology has to offer.” No-one in a position of authority or influence is any longer suggesting F1 should move away from the latest generation of hybrid ‘power units’ back towards big naturally aspirated engines, which many fans might consider more evocative. Even Red Bull’s Christian Horner, who not so long ago was championing such a move, has changed his mind.

“The romantic in me says go back – loud noise, normally aspirated,” Horner says. “Emotionally, a high-revving V10 or V12 engine would be a wonderful thing to have back in F1. But unfortunately they’re rather outdated now. “The technology in these [hybrid] engines is phenomenal. We’ve now got a period of stability, so it’s important that F1 makes the right decision for the future.

The automotive sector is moving an awful lot at the moment and what technologies are going to be relevant then? Because when that engine comes in, that’s going to be for a five- to 10-year period.” Abiteboul points out that F1 engines are increasing in power on average by three per cent a year – or to put it another way, given there is a limit on both fuel capacity and fuel flow, they become three per cent more efficient each year. This, he says, exceeds the 2.5 per cent target for annual efficiency increases demanded of global industry by the United Nations at the 2015 climate conference. “Obviously it comes at a huge cost and lots of technology,” Abiteboul says. “It can’t be transferred to all cars on the planet, but still it does represent an element of the answer to the problem.

“The average efficiency of an internal combustion engine is in the region of 30-35 per cent. We are above 50 per cent in F1. That’s massive. If this type of efficiency was affordable for all mass-market products, that would be a massive contribution to CO2 emissions. So that’s something that we need to keep at the edge of in the future.”

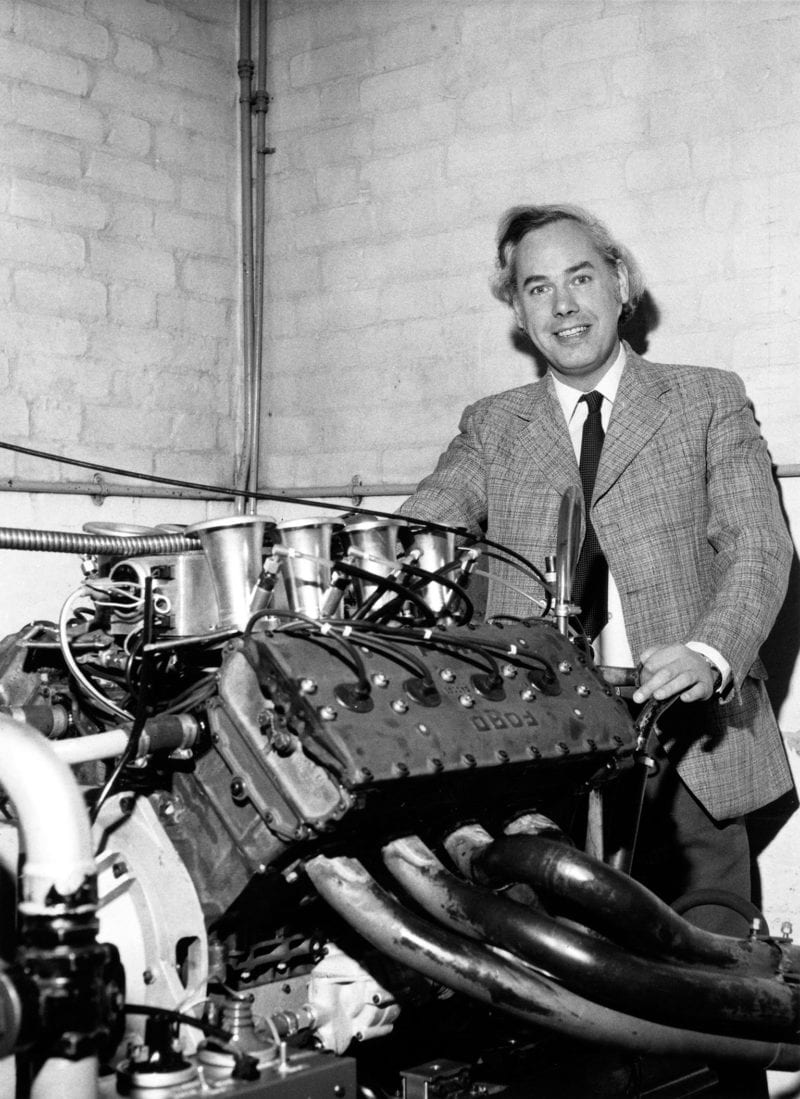

While many fans would love a reintroduction of a big V8 like Cosworth’s famed DFV, many now think they’re outdated

Getty

And what is that future? The road-car industry is on a huge electrification drive, but F1 cannot embrace pure electric power to the same extent. Todt says: “At the moment, you can only consider F1 with a hybrid engine. You cannot envisage Formula E substituting F1. There is not one [electric] race car able to do 300km at the F1 speed today. It will be decades before it can happen, if it does. Today, hybrid is the proper choice. The next step is to see how we can secure greener fuels.”

A significant part of the electrification drive in the road-car industry includes hybrid engines, and it is here that F1 feels it can play a major part in driving down emissions by developing engines that run on synthetic fuel – where carbon is captured from the atmosphere to make the fuel, so it is effectively carbon neutral.

“We are talking about e-fuel, fuel that will not be composed of fossil energy,” says Abiteboul. “This will be a game-changer, I think. We need to make sure that F1 remains a demonstration for game changers.” If this sounds like a car manufacturer justifying its involvement in F1, it is. But the sport as a whole is fully signed up to this plan. F1 chief executive Chase Carey sees F1 as “a platform to put forth what is possible for a broader industry that we’re at the forefront of; that’s an important role”.

There may be those reading this who say, that’s all very well, but why does F1 have to bow to the demands of the manufacturers? Why, indeed, does it need manufacturers at all?

That’s not far off the position F1’s owner Liberty Media held when it bought the sport in January 2017, when Liberty talked about simplifying engines and introducing what F1 managing director Ross Brawn described as “a great racing engine that everyone admires and enjoys”. But it did not take long for Liberty to realise that F1 would struggle without the manufacturers.

Liberty set out with the aim for 2021 of getting rid of the MGU-H – the motor generator unit that recovers energy from the turbo and which is central to the huge efficiency gains of these engines. But the manufacturers wanted to keep it, and the FIA was not prepared to abandon hybrid or road relevance altogether. As Liberty discovered, it was impossible to square the circle of road-relevant hybrid F1 engines without car manufacturers being involved.

The question of whether F1 can afford to ignore road relevance has become an academic one that is not taken seriously among F1 stakeholders. In doing so, the sport might be more appealing to a certain portion of hardcore racing enthusiasts, but it would also become significantly more vulnerable to questions from outside regarding sustainability, against which – under the current trajectory – F1 is working hard to insulate itself.

F1’s new rules are hoped to close the performance gap between teams to improve the racing, and trim the big hitters’ spending

Getty

With manufacturers, there is always the threat that one or more will one day decide the sport no longer meets its needs. But in pursuing the current path, that risk is minimised. Take the alternative route, and F1 would effectively be driving the manufacturers out, because as one puts it “no manufacturer would be able to justify the outlay on an irrelevant power-train”. In doing so, F1 would be creating an engine supply crisis for itself – as well as voluntarily putting itself in a very vulnerable situation.

For some, the 1970s, with a bunch of privately entered cars powered by Ford Cosworth engines against Ferrari, is held up as a panacea. But others would argue that panacea is a chimera. After all, the Cosworth was a manufacturer engine itself – it was just a single offering in the market place. And why pick the 1970s as an ideal? Why not the 1950s, when the sport was largely Alfa Romeo v Ferrari v Lancia v Maserati and sometimes Mercedes and Lancia? Or the 1980s, when Honda, BMW, Porsche, Ferrari and Renault supplied engines? Or the 2000s, when BMW, Ferrari, Ford, Honda, Mercedes, Renault and Toyota all faced off? The truth is that F1 has always involved manufacturers, and the draw of huge global brands such as Mercedes and Ferrari is part of its appeal.

In the past three years, F1 cars – at least over one qualifying lap – have reached performance levels never seen before, despite being heavier than they have ever been. But the racing has often been criticised as processional.

In an attempt to fix this, F1 has come up with a new set of rules, now slated for introduction in 2022. They will slow the cars by an estimated two to three seconds a lap, but it is hoped they will also make the cars more raceable by reducing the disparity between teams and drastically reducing the loss of downforce experienced by one car following another.

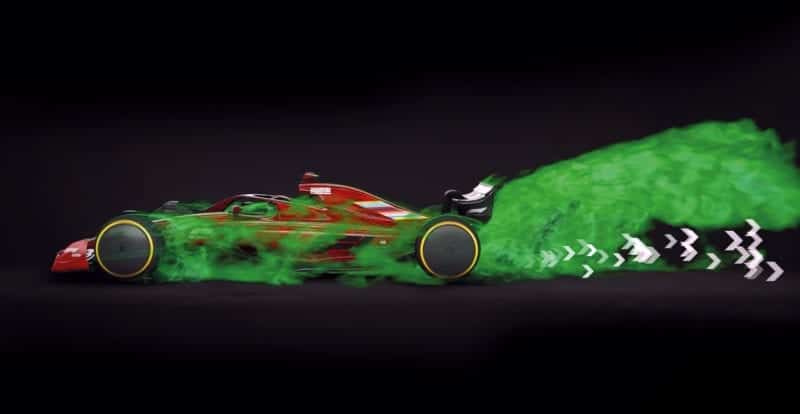

The new-generation cars aim to tidy up the aerodynamic wake, to allow others to follow closer

These rules were created by a team collaborating across F1 and the FIA, and forced through by Brawn, Carey and Todt last October after months of debate with the teams, founded on scepticism among the top teams that the rules would do what was intended.

There was concern not only about the prescriptive nature of the new regulations, but also that they would produce fundamentally flawed cars, which were blighted by understeer. Those concerns remain, even if teams are reluctant to express them publicly for now. One leading figure did say: “The new rules have very worthy objectives and are aiming for a lot of the right things, but the proof of the pudding will be in the eating, in terms of whether they have been successful or not.”

The teams’ concerns centre on the fragility of the aerodynamic behaviour the car is built around. The aim is to control the wake in such a way that it has the lowest possible effect on the airflow experienced by the car behind. But senior figures say that to maintain these properties, and not break the wake effect, needs something not far from a spec car. In that sense, there is a danger that the rules will set up an inherent and unavoidable tension between the ambitions of F1 and those of the teams in trying to make faster cars. And that if the teams succeed in adding downforce to the cars, the rules are destined to become less effective over time.

To this, Brawn responds: “Help us make them better.” A remark that might cause some spluttering among the top teams, who would argue that they were making this point throughout last year but were effectively ignored.

Brawn mentions the people at the centre of creating the new rules – the FIA’s Nikolas Tombazis, a former Ferrari chief designer, F1’s technical chief Pat Symonds, a former Renault technical director, and ex-Williams aerodynamicist Jason Somerville.

“They are all very experienced people and they’ve done a great job designing a car we think will be much better to race,” Brawn says. “These aspects that are being highlighted may cause some deterioration of the benefits, but it doesn’t lose it completely and certainly nowhere near where we are with the current cars.

“And you have to remember that if we didn’t do anything, these cars would just get worse and worse and worse. I wouldn’t pretend that I can guarantee these are 100 per cent perfect, but they’re a long way towards being a big improvement on what we currently have.”

Though at the technological forefront, McLaren is still an advocate for cost caps

Getty

However the new cars behave on track, they will be driven by what is an especially promising new generation of talented, likeable and relatable drivers, characteristics that have only been enhanced by the lockdown as many broadcast themselves live on the internet doing e-racing. Charles Leclerc and Lando Norris, in particular, have been social media hits, as have, if perhaps to a lesser extent, Leclerc’s long-time rivals and buddies George Russell and Alex Albon.

At 35, Lewis Hamilton will probably be around for another three years or so, possibly more, but his successors have already emerged in the shape of Max Verstappen and Leclerc, who have both demonstrated they are of the very highest calibre.

Add to them the likely emergence into the full limelight of Norris and Russell once they get front-running cars, the jokes and sunshine provided by Daniel Ricciardo, and the handsome and engaging Carlos Sainz moving to Ferrari, and you have a set of superstars likely to keep the fans excited. With a budget cap on teams, though, Hamilton may turn out to be the last of the super-earners – Verstappen’s deal at Red Bull is believed to be less than half Hamilton’s earnings, while Leclerc’s new Ferrari salary is a chunk less again. And the size of teams – with more than 1000 employees at the likes of Mercedes and Ferrari – has reached its peak and is about to come down, at least in terms of those designated solely to F1. Paradoxically, Liberty’s projections for the future of the sport – admittedly made before the coronavirus hit – are all for growth. It expects broadcast rights, race-hosting fees and sponsorship to remain the three biggest income streams, and for revenue to increase, particularly through a transition towards direct-to-consumer television offerings, known as ‘OTT’, for ‘over the top’.

F1 was due to break new ground with a race in Vietnam this year, before the world went into lockdown

Getty

Another income-driver will be an increased number of races. This year’s schedule would have been a record 22 grands prix, and it’s not hard to see how that could easily creep up to 25. Saudi Arabia is expected to join the calendar by 2023, F1 is working hard on a race in South Africa – likely a return to Kyalami – and continuing its efforts to find a second event in the USA.

The desire will be as already stated – to retain the iconic, historic races such as Silverstone, Monza, Spa and Monaco, and add to them lucrative new events that expand the sport’s global reach, and therefore its potential to increase its earnings.

How exactly this all pans out after the coronavirus remains to be seen, but F1 insists that it has no fears about the viability and appeal of the sport for the coming decades. “Inevitably we are going to be operating differently in the future than we did before this happened,” Brawn says. “Just like working from home.

“Will it ever just go back to exactly how it was? I doubt it. It’s a bit like security at airports. You and I can remember when there was no security at airports. Then we had all the problems and now you have to go through security. And you don’t even think about it any more. It is just part of the procedures and patterns of life. And I’m sure that is what will happen. We will have to fit into that new tapestry of life and we will do things differently, but I don’t see them stopping.

“F1 was making real progress in terms of the countries it was going to, the engagement of the fans, how we presented the sport. This has been a bit of a hold-up, a pause button, but we will adapt and adopt everything we need to be able to continue that trajectory.”

Andrew Benson is BBC Sport’s chief F1 writer

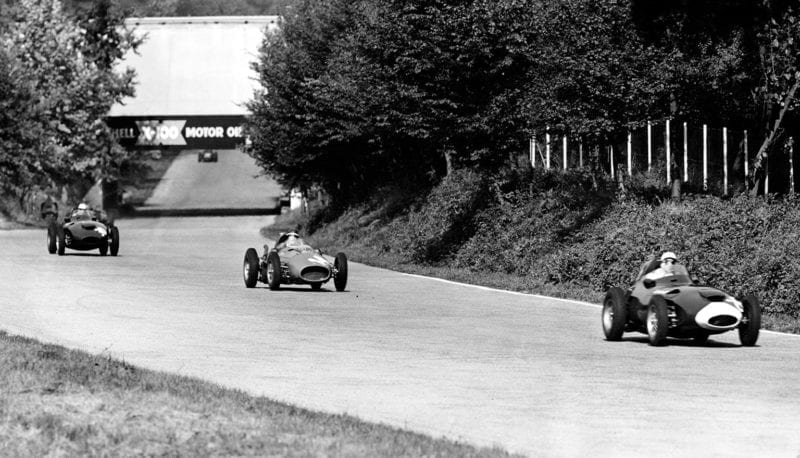

F1’s stars of the 1950s: Moss leads at Monza in 1958, his Vanwall ahead of Hawthorn’s Ferrari

Getty