1981 French Grand Prix race report

Inconclusive Dijon-Prenois, July 5th The most important aspect of the 1981 French Grand Prix was that it saw the return of the Goodyear Tyre Company to Formula One. It will…

Back in October 2018, Bloodhound hit major financial troubles and its appointed administrator, FRP Advisory LLP, appealed for interested parties to save the project. There were several, but when everything went quiet it became clear that, despite FRP’s reputation for saving F1 teams, no saviour was about to step forward for Richard Noble’s troubled operation.

Until, that is, early in December, when Charlie Warhurst messaged his father Ian, who had just retired after selling his very successful Dewsbury-based turbocharger company, Mellett. Within a week the 49-year-old engineer from South Yorkshire found himself meeting men with angle grinders as they were literally preparing to cut up £25m worth of beautiful machinery that had been painstakingly and lovingly created by the team Noble had formed in 2008. Thus would end the dream to boost the number of STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering & Maths) students in Britain with an engaging and brilliant engineering adventure… oh, and aiming for 800 and then 1000mph on land.

“I’d retired and was sitting around when Charlie sent me a text on the Friday night and said, ‘Hey, Dad, have you seen… Bloodhound is for sale and you can buy it’,” Warhurst says. “I assumed that was just a way of getting to the next stage, while protected from creditors. That someone would come along and sort it out.

“I was interested from the sidelines. I’d got a gold membership [to the Bloodhound project] for my 40th birthday from my brother, and I’d followed ThrustSSC keenly. I was one of those getting up early and checking the videos to see how it had got on.

“Then I thought, ‘If it goes to auction, it’s going to get scattered around the world. You won’t be able to regroup even if the car itself stays intact.’ So, I just thought I could buy all of it. Rather than going to auction, if I put in an offer to buy everything and ringfence it, I could hang on to it and hand it back whenever anyone’s ready for it.”

He contacted Noble on the Sunday afternoon, and by Monday was talking to administrators Andrew Sheridan and Matt Whitchurch. But what might have seemed like a simple proposition, buying the assets but not the debts of a project that had run out of steam, soon turned into something far more complex thanks to the myriad components that had been supplied by sponsoring or supporting companies. Who owned what? What had been donated and what was on loan? The Rolls-Royce Eurojet EJ200 turbofan engines, for example, belonged to the Ministry of Defence.

“I could see why anybody else with a business, worried about legal stuff, would not want to go near all this with a bargepole.”

Warhurst met engineering chief Mark Chapman at the team’s base in Bristol, the lease on which was very expensive, and that was pushing the administrators because they had to keep paying but had no income from the project.

“Messy is the wrong way of putting it,” Warhurst says, not wishing to be disrespectful to what Noble had built. “How would you expect it to be, after 10 years? I mean, that’s how it works. People do favours, and it’s done on a handshake, which is absolutely fine. It would be nice if I had all sorts of contracts. But it wasn’t clear, and the information that was available was in five pallets of files that were all over the place.”

The rent was due at the end of the month and with nobody to pay it, the administrators wanted Bloodhound out. But moving a 44-foot-long jetcar requires expensive equipment and handling. Sacrilegious as it seems, they were going to butcher the car, cutting it into more easily handled pieces.

After all that blood, sweat and tears, and clever research and design that had created something even safer and better suited to ultra-high speed on land than its Sound Barrier-piercing predecessor ThrustSSC, it would then be sold off at scrap value.

“Had I not gone down on the Tuesday, there were literally men in the car park with angle grinders waiting to come in,” adds Warhurst. “And I realised that if I didn’t do something there and then, Bloodhound was going to go into the skip and that would be the end of it.”

Warhurst chooses not to disclose how much he paid, but he took the massive step of putting his money where his mouth is and went ahead with one of the bravest business decisions in land speed record history.

“Had I not made the first phone call on that Friday, whatever happened to Bloodhound I’d have just gone, ‘Oh, that’s a real shame.’ But because I was stood there and effectively felt as though I would be

the one who’d be responsible for actually letting that finally happen. I kind of thought, ‘I’m not sure I’d be able to live with myself with that. Even if it just goes into a museum as a whole car, that’s the very least the project deserves.’

“Now I like joking about that I’m on the rebound. I sold my last girlfriend [Mellett] and now I’ve got another one [Bloodhound].”

A sexier and rather more demanding one, though.

“By the following Friday lunchtime, I’d signed up, and Bloodhound was mine.”

Warhurst, who loves restoring vintage Rolls-Royces and owns several of them, doesn’t just talk the talk, he walks the walk, too. His retirement probably lasted four days, but he has the full support of his wife Nicola, who has a background in marketing, and their three children, Charlie (19 and a keen Bloodhound model rocket-car racer), Thomas (17) and Joe (13).

But where does the Bloodhound team go from here?

While he is clearly passionate about the project, Warhurst is, first and foremost, a businessman.

“When I first got involved I was chatting to Richard [Noble] and assumed I’d be letting him get on with it. I had no idea that I would end up as the CEO. I went to see him a couple of times for advice, but he was quite keen to get me to say that I would run the project. Actually, I wasn’t going to, I was just going to help out. But the more I got into it, the more I thought, ‘I can afford this, I can see a path forward, make sure the right people are in the right places and get the plan in place. And if I’m putting my own money into it, I don’t want just to be somebody who keeps sticking it in and waits to see what’s happening’.”

Having stabilised things, he told the key team members he was keeping on to go and enjoy Christmas. Then in the New Year the skeleton crew – pilot Andy Green, Chapman, aerodynamics guru Ron Ayers, financial director Rick Sturge, operations director Martin Roper, head of engineering operations Stu Edmondson, commercial director Ewan Honeyman and PR Jules Tipler – began formalising the forward plan under the aegis of Grafton LSR Ltd, and relaunched the project on March 21st.

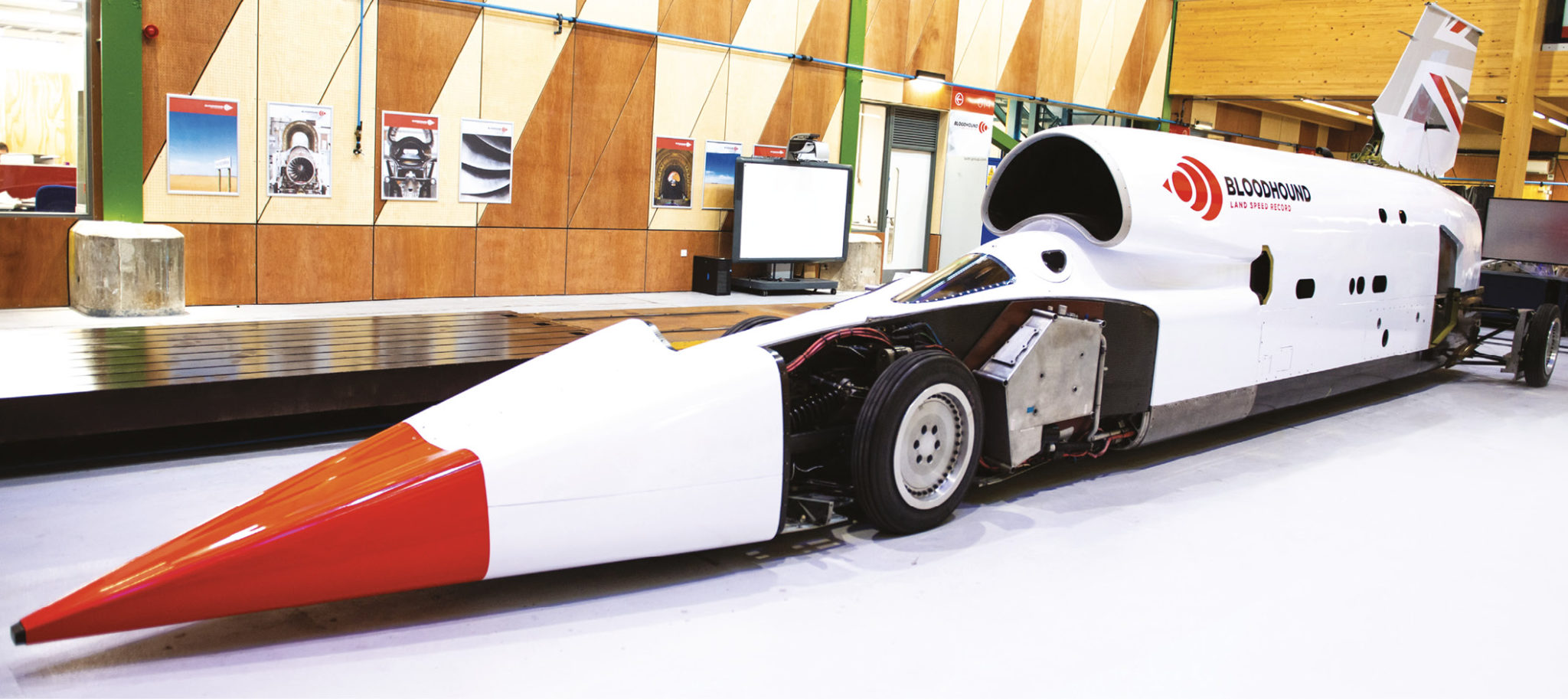

Warhurst has managed to keep Rolls-Royce on board, but the emergence from administration has opened up all of the sponsorship sites on the car again, which is why it has been wrapped for the time being in white with a red nose – to provide a clean canvas for future investors.

Bloodhound’s STEM activity remains impressively far-reaching, and Warhurst admits freely that what interests him the most “is the aerodynamics and engineering. I’m not a massive speed freak at all. I’m a mechanical engineer and I’m determined that the legacy of the project should be that the Bloodhound Education Charity continues for the next 20 years, inspiring young people and adults alike to be interested in engineering.”

“I’m not sure I could live with myself if it went into a skip”

He committed fully to getting the project to the stage where initial high-speed testing could be conducted.

“I can afford to pay for that,” he said when we talked back in May. “But after that point I’ll be like, ‘Okay, I think I’ve paid for enough now.’”

That’s the point where the project must have raised enough sponsorship to keep progressing. When the administrators were seeking buyers there was talk of £15m to get to 800mph, and another £10m to get to 1000, but he is sceptical of such figures.

“I don’t want to pay for everything myself, but on the basis that hopefully I’ll get the money I’m loaning the project back at some point. But I’m not expecting to make any money out of it. That’s not the plan.

“But if this project is pushing the bounds of known engineering technology, and the government wants to put a grant in to help us solve an engineering problem that will then have use in the wider world, why not?

“As I stand here now I might be stupidly optimistic but my view is that I don’t see any reason why we won’t be able to do the high-speed testing and then 12 months after that get ourselves out and going for the first land speed record attempt in the digital era.”

On July 10 the team proudly confirmed that Bloodhound will run on the specially prepared 12-mile dry lake bed course on the Hakskeenpan in South Africa’s Northern Cape this October.

Two years ago Green ran successful 200mph UK trials at Cornwall Airport in Newquay. Now the car has been converted to high-speed testing spec. This time the target will be 500, where the stability transitions from being governed chiefly by the interaction of the wheels with the desert surface to being controlled by the aerodynamics. This is the next key milestone prior to aiming for the initial 800mph target.

So, is this a genuine rescue mission, or just a stay of execution?

It’s impossible to say for sure at this stage. But Warhurst is a genuine fellow with a proven business track record and innate determination and passion, who has laudably spent his own coin thus far. Richard Noble remains a friend of the project, and many key team members are still fully committed. And right now, the future for Bloodhound is bright again.