Service deva-station

Sir, In reply to Mr Hungry I can only say that this and the neighbouring farm are losing 40 acres of good agricultural land and ancient woodlands, to a monster…

The hype of the Goodwood Revival may centre on Ferrari 250s, Aston Martin DB4 GTs, rumbling Cobras and enduring E-types. But nestled in the entry for this year’s event is a car that’s arguably more significant and storied than all of the more extravagant exotica in the paddock combined.

The Zerex Special is probably the most important and influential car you’ve never heard of. This diminutive, unassuming prototype is the car that first displayed Roger Penske’s cunning engineering genius. It’s the car that first wooed Bruce McLaren into wielding a spanner in his own name, and in many ways launched the global automotive empire that’s become his legacy. In a former life this car also competed in Formula 1 and, on top of that, it sowed the seeds for the legendary Can-Am category.

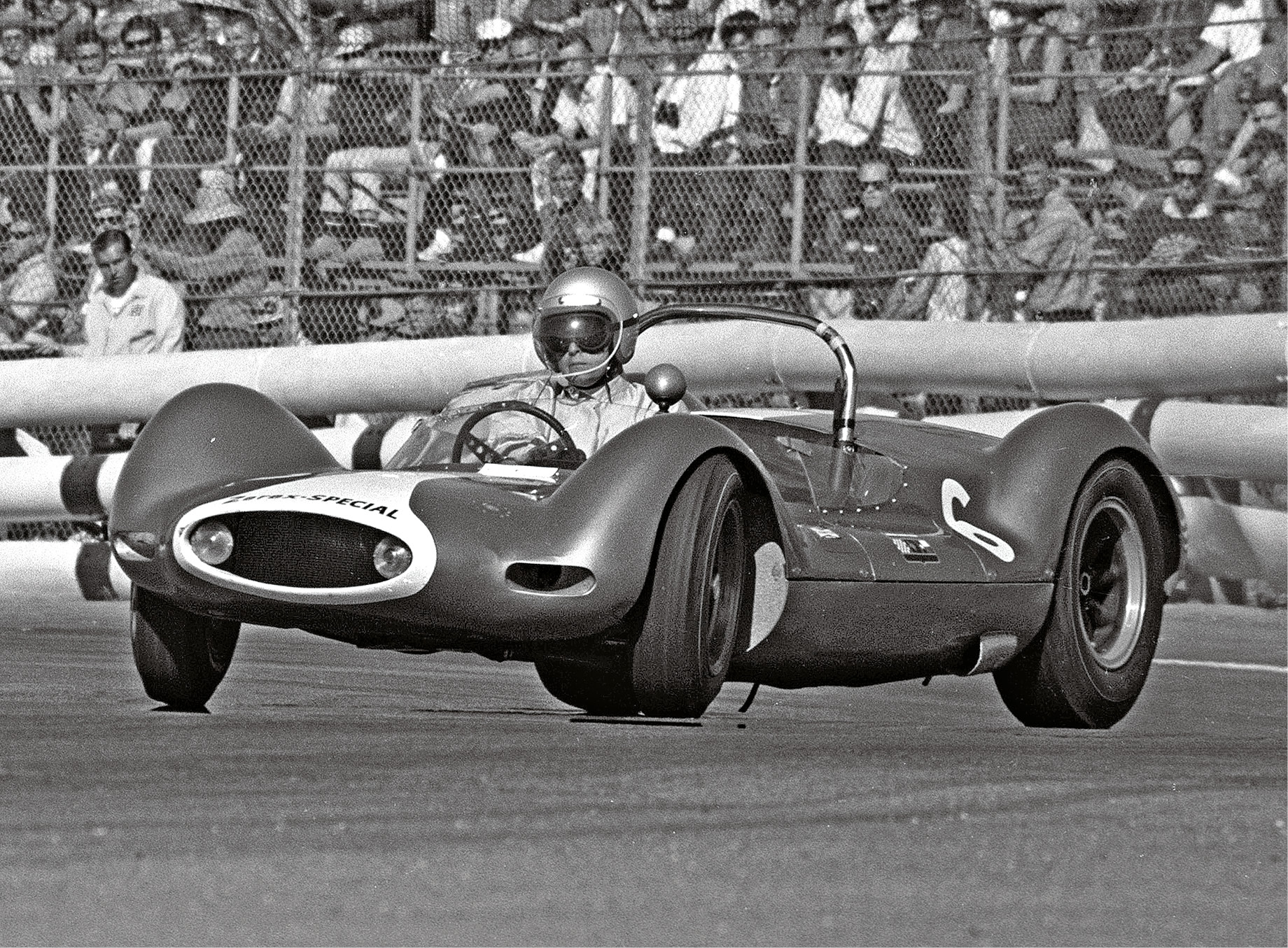

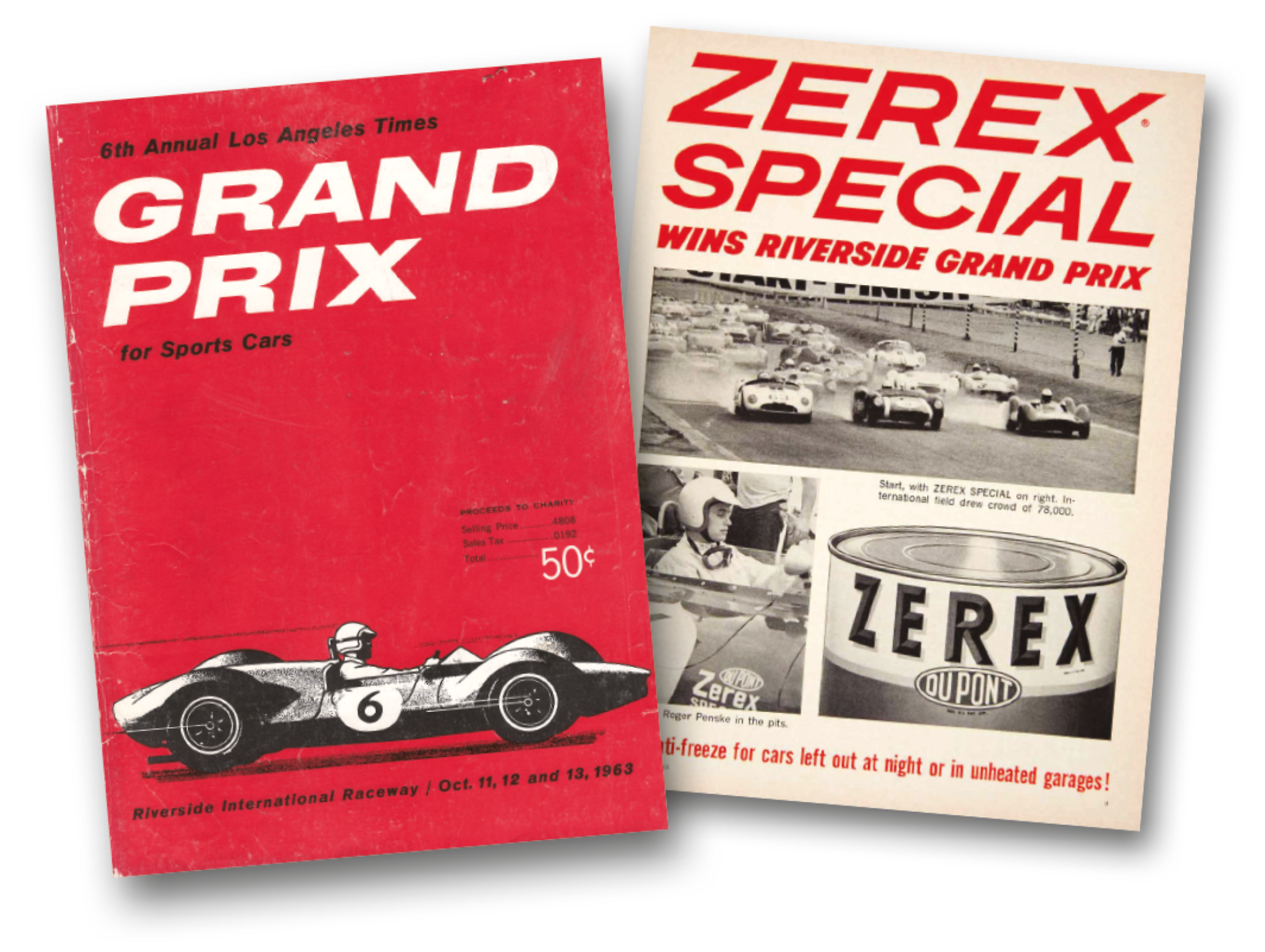

While the Zerex has a bit of a cult following across the United States West Coast – thanks to Penske’s exploits with it in the early ’60s – its competition pedigree in the UK was brief, but highly successful. Plus, to us, its name sounds like a photocopier – it’s not. Zerex Special was actually a brand of antifreeze from Dupont, Penske’s sponsor. At the time America frowned on monetary sponsorship in motor sport, so Penske simply stuck two small white stickers on the sides and gave the machine the moniker of the sponsor. The Zerex Special it became.

So, what is the Zerex Special? It’s actually not an easy question to answer. “This car is about four cars in one, so it’s got a pretty complex lineage,” says Greg Heacock, the car’s proud owner, and the reason this piece of history is still alive. After an exhaustive restoration lasting almost two decades, both the story of the Zerex Special, and the car itself, have been pieced back together by the work and dedication of Heacock. It is a story that crosses continents and eras and includes the original engineering and design team as well as a Motor Sport.

First, let’s cover the car’s backstory. The Zerex actually started life as an ill-fated Cooper T53 F1 entry. Chassis F1-16-61 was freshly built when it lined up on the grid for the 1961 United States Grand Prix at Watkins Glen in the hands of American entrant Walt Hansgen. It only lasted 14 laps, when Hansgen crashed while trying to avoid the spinning Lotus of Olivier Gendebien, ripping a corner off in the impact and twisting the chassis.

That should have been game over, were it not for another American driver in that race – Roger Penske. On one of only two F1 starts in his career, Penske had rented a John Wyatt Cooper T53 for that race and spied an opportunity. He bought the remains of the damaged chassis and rebuilt it with the intention of using it for Formula Libre races, but went a bit further.

Having studied the Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) rulebook, Penske spotted an early trend for creating central-seat sportscars, which enjoyed better weight distribution and handling characteristics. He figured an F1 chassis would be the perfect base for one. However, the cars still had to have two seats side-by-side, but no mention was made to the size of the second seat, or if anybody ever had to actually fit into it.

In the true Penske style of always looking for the unfair advantage, no matter how slight, the team fabricated brackets to fit a monkey seat – barely large enough for a child – to the side, underneath a hatch in the skin of the newly-created sidepod. Penske crammed himself into the tiny space, knees jammed to his chest, well above the bodyline, to prove to concerned scrutineers that it constituted a passenger seat.

He added custom-designed sports car bodywork over the top and fitted a 2.75-litre Coventry Climax engine, significantly larger than the 1.5-litre four-cylinder unit used during its brief F1 career.

Penske and what was then called the Updraft Special – named after his engineer Roy Gane’s Pennsylvania-based Updraft Engineering company – were an immediate hit during 1962. The combination won multiple races by handsome margins, culminating in the USAC Road Racing Championship title in the first season.

It was during 1963 that the car, now known as the Zerex Special, morphed into its third iteration. Still driven by Penske, but sold to John Mecom’s eponymous racing team, the chassis was changed dramatically with the bottom tubes of the frame widened enough that two seats would fit between the frame rails, this time with the driver’s seat being moved to the right and a proper passenger seat fitted alongside to avoid the ever-tightening rules.

“This American creation bending the rules outraged people”

Despite the more compromised design, the Zerex still succeeded. Keen to test his creation farther afield, Penske entered the 1963 Guards Trophy race at Brands Hatch. Against the heavier and less nimble Cooper Monacos, Lotus 19s and Ferrari 250 GTOs, Penske and the Zerex dominated. It may have had two seats by now, but there was unanimous feeling that it wasn’t built in the spirit of a true sports car of the time.

“I was at that race as a boy, and I remember being absolutely outraged at this American creation coming over and blatantly bending the rules,” says Frank Catt, owner of Wealden Engineering – Heacock’s designated custodian of the Zerex while it’s in the UK. “We were horrified. It was a completely illegal car as we saw it, yet it got through scrutineering on a technicality and won the race by a country mile. I remember all the chatter being: ‘Is this the way sports car racing is going, then? This Yank chap can turn up with buckets of cash, make what he likes and call it a sports car?’ In those days we were purists and Ferrari GTOs and Jaguar E-types were brand new cars, and this Zerex was totally alien and mind blowing, but that was Penske all over. I’m amazed that this car has ended up with me all these years later.”

After 1963, Mecom opted to offload the now two-seater Zerex. Bruce McLaren had a firm relationship with Cooper, having driven for the works team in F1 since 1958. He liked the development potential of a car like the Zerex, and bought it, making it the first racing car McLaren ever owned himself (the tiny 1929 Austin 7 he began his career in was bought by McLaren’s father, Les, and then commandeered by Bruce).

This is where the key part of the Zerex story occurs. McLaren fitted a huge 3.5-litre Traco-Oldsmobile V8, with bulging exhaust tailpipes protruding through the now shorn-away rear bodywork. But the old chassis simply didn’t have the torsional rigidity to stand up to that sort of torque, so McLaren cut the bodged centre chassis away and replaced it with his own, stronger tubular-frame design. Now called the Cooper-Oldsmobile, Bruce entered it into the British and Canadian Sports Car championships under his own fledgling Bruce McLaren Motor Racing team. After some oil pressure problems stopped the car at Oulton Park, McLaren dominated round two at Aintree, beating Jim Clark’s Lotus 30. McLaren would go on to win that year’s Guards Trophy and was only denied glory in the RAC Tourist Trophy at Silverstone by a clutch failure.

That was as far as McLaren’s relationship with the Zerex went, but it had served its purpose. Bruce McLaren Motor Racing had made its first real impression on the sport, and constructed its first racing chassis. McLaren would split with Cooper’s F1 team and run his own F1 concern from 1966. That probably can’t be totally credited to the Zerex, but it was certainly a launchpad for McLaren’s independence and remains the first car it ever fabricated.

As for the Zerex, it was sold to one-time F1 starter Dave Morgan for 1965, who raced it sporadically before it changed hands again, to Venezuelan Leo Barboza and eventually disappeared entirely after 1966.

The remains of that car are still thought to be in storage somewhere in South America, but its exact location and condition are unknown. So, if that’s lost in the wind, what’s this Zerex? Remember that bit of old chassis McLaren cut away and discarded?

“It all started when I was working to restore an ex-Pete Lovely Lotus 19, because I’ve always had a fascination with the Coventry-Climax engine and the cars it powered,” says Heacock, a Seattle-based businessman and amateur racer. “Through that project I built a good relationship with Pete and his mechanic at Rosebud Racing in Texas, Jock Ross. We started looking for the correct Climax engine block for the Lotus, and knew it was in the UK. I already knew Frank [Catt] as he was a big Ford GT40 man and we’d struck up a friendship as I’m in the UK quite a lot – I even married a Brit!

“We traced the block to a private seller, who we met at the Beaulieu Autojumble. There we were with a garden trailer, and this guy with his garden trailer full of junk and it was like a scene from Steptoe & Son! We found the block with the right numbers for Pete Lovely’s car, but there was also this big chunk of racecar frame, boxes of sheetmetal and fittings, brackets and other cut-up bits, which the seller thought were from a Lotus 19. We bought the engine block for £1500 and rest of the bits for £250, got them home and quickly realised the bag of bones wasn’t from a Lotus at all.

“Frank thought he recognised the car, mainly from the rear air scoops, and swore he’d seen it before. We got some help from [Motor Sport historian] Doug Nye, and also the LAT Photographic agency, which sent us all the shots they had of the Zerex. We were counting rivets to try to identify the bits!”

With the bones of the original chassis with Heacock, his connection with Lovely and Ross yielded more parts to the puzzle. Ross put him in contact with Penske’s original mechanic Gane, who in-turn knew Harry Tidmarsh, who constructed the original sports car bodywork for Penske at his workshop in Philadelphia. Photos were sent back and forth, and eventually all parties agreed. It was unquestionably the centre section of the original Zerex Special chassis.

“We made a good fist of identifying it, but Roy Gane really called it as he recognised some of the Cooper chassis modifications he’d made originally, such as moving the shifter outboard and passing the shift rod through the right cockpit frame tube to accommodate the exhausts,” explains Heacock. “That’s when Roy and Harry said ‘Well, if you’ve got this much of the car, we’ve got a load more here in boxes.’ We could even pick which iteration of the car we wanted to rebuild – but the single-seater ‘Penske spec’ for me was the real Zerex Special, so that’s what we went for.”

The remains were transported to Seattle, where the frame was built around the original pieces, supplemented by original Cooper parts taken from another restoration of Steve Froines’ T53 in California.

“We took it all to a well-respected Lotus 19 fabricator called Archie Hodge,” says Heacock. “He’d just built a new frame for Froines, so we took his old one and put it into the mix with the piece of shit we had to essentially create a new Zerex frame. We also got the original Armstrong suspension dampers, brake calipers, the steering wheel, Cooper shifter knob, full dash, front radiators and air scoops. Suddenly we had all four corners and things were coming together. We had to fabricate things like the wishbones and the exhaust parts as they were ratty.”

But there was also some customary Penske magic with the original chassis that wasn’t immediately noticeable.

“When we got the two Cooper frames together, we realised the Zerex one was shorter by about an inch and a half,” adds Heacock. “We spoke to Roy about it and it turns out they shortened the chassis so they could make the nose more pinched and lower for less wind resistance. So, it wasn’t enough that this was already a single-seater, not a sports car, but they did that too for some more unfair advantage! The whole thing is a beautiful cheat from front to back.”

The engine is, as you would expect, a Coventry Climax unit from Crosthwaite & Gardiner. But this time it’s a 2.5-litre.

“The way they used to get 2.75 out of the units was by machining the piston liners until they were almost see-through,” adds Heacock. “They’d get a race or two out of them and then they’d just erode or crack and need replacing. In modern engines, Crosthwaite gets more power out of the 2.5 with some port work, and it’s more reliable.”

Some could call this iteration of the Zerex a reimagining, or an evocation, but that’s not quite right. This is as real as it can get. Underneath is the metal and soul of the original Penske-built special, and it goes the extra mile for authenticity on top, too.

“Once the chassis was done, we got started on the bodywork,” continues Heacock. “We had a fair few bits already, like tracings and a few body parts. But there were a few panels around the back that there are no good images of in-period. It’s quite complex how it all tucks away back there. So we went to Harry and he got out the same 55-gallon drum he used to make the original ones, the same mallet he used almost 60 years ago, and a piece of aluminium and just hammered it all out again. You can’t get much more original than that.”

After acquiring the original chassis parts in 1999, and intensifying the project over the last five years, the Zerex finally returned to the track last year. Sadly, too

late for Tidmarsh, Ross and Lovely – who have all since passed away – to see it run.

So what’s it like to drive the culmination of the work of so many great people, reliving the glory days through the project?

“It’s an incredibly special car to drive and you can feel the history behind it,” says Heacock. “You can get it crazy sideways and hold it due to the long wheelbase and the engine has so much torque you can basically steer it on the throttle. But it’s the history that soaks into you. Somebody once suggested that we re-trimmed the steering wheel, I told them we’d be crazy to do that – Roger Penske and Bruce McLaren once held that!

“Working with people like Harry, Roy and Jock and seeing their methods was amazing, too. I once watched them gas-weld aluminium, which I knew they did back then, but I’ve never seen. I’ve only TIG-welded before, but they just got the torches out and it was beautiful. They were so fast too, so old school – such beautiful work with the simplest tools. It shows that we rely far too much on modern technology to do this stuff for us now. We just don’t use our hands and our brains enough anymore.”

Now back and running, the Zerex made its Goodwood debut during the Members’ Meeting back in April, and will now be one of the star attractions at the Revival, where Heacock will race it in the Whitsun Trophy.

During Motor Sport’s podcast with Penske himself earlier this year, we informed him of the Zerex’s restoration. Penske was visibly moved by the project, and admitted to having a strong affinity for the car he built to bend the rules. Heacock adds that he’d love for Penske to one day drive it again: “I’d love to know what he thinks of it.”

For now, the car’s in the UK for us to enjoy, before heading back to the States. “There’s a few people in America who weren’t too pleased that I brought it straight to the UK as they wanted it at places like Monterey Car Week, but there’s time for all that,” says Heacock. “People want to see these cars and the Revival is one of the best showcases. I’m not one to have something like this and hide it away.”

And what about the next step? Is there anything left unsettled after this epic project?

“I’ve actually been trying to track down the McLaren version of the car in Venezuela,” he says, with a grin. “I’d love to buy it and restore it and put it alongside this one, to have both cars together again, after so long. That would be truly amazing.”