Motor Sport

After two years at the same price, we are reluctantly compelled to bow to increasing production costs and raise the cover price of MOTOR SPORT by 20p to £1.20. This…

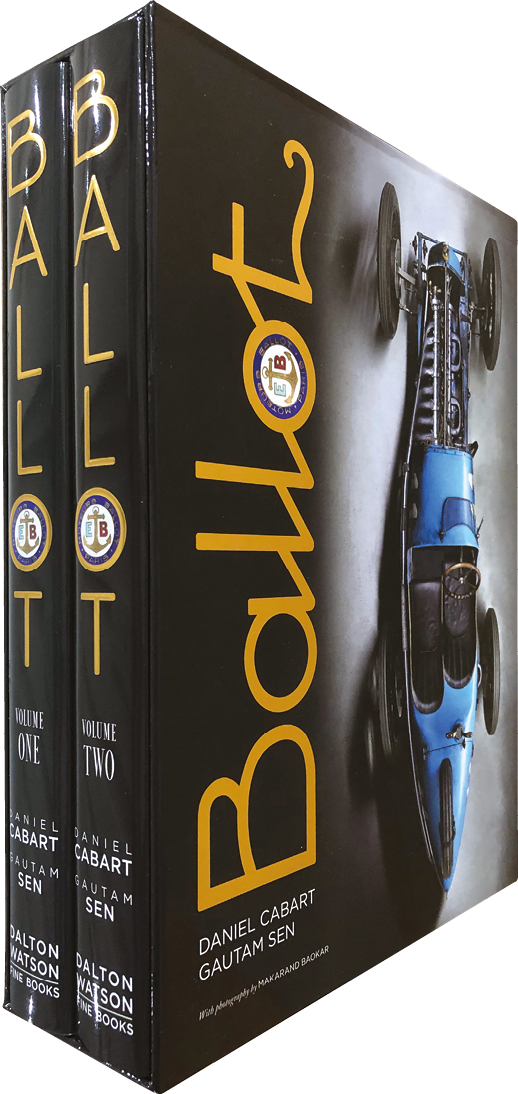

Daniel Cabart and Gautam Sen. Published by Dalton Watson, £270, ISBN 978-185443303-9

Ballot is hardly a famous name now, yet after WWI the company built sophisticated racing and touring cars on the same plane as Sunbeam, Delage and Bentley, and contested Indianapolis and grands prix with cars which influenced Miller, Bugatti and the wider sporting automotive world. In other words, Ballot is more significant than you realise.

In two comprehensively illustrated and well-produced volumes the authors trace the path of this French enterprise, the path of so many manufacturers – driven by a passionate engineer, trying to build a high-quality product and finding the profits weren’t there to sustain it. There are parallels with Bentley, especially in the sad fact that both W.O. and Ernest Ballot lost control of their eponymous companies – in the latter’s case, forced out by the board even before in 1931 the firm was finally subsumed into Hispano-Suiza.

Cabart and Sen offer a staggering amount of detail in 920 pages on a marque which, Orson Welles-like, started with its finest work and gradually declined, failing to retain or capture either the luxury market or the sustaining bread-and-butter trade of Citroën and the like. Delving deep not only into the firm’s records but officialdom at all levels, the authors depict Ballot’s successful early stages supplying fine engines to many other makers for cars, boats and even airships, before putting its own anchor medallion on the prow of a new range of its own cars. Detail is impressive – plans as well as photos of the firm’s Paris works, a wonderful post-Art Nouveau brick edifice – with extensive quotations from reports, prospectuses, and correspondence to depict the firm’s technical triumphs and economic trials.

And technical triumphs there were: remarkably, M. Ballot was persuaded by engineering genius Ernest Henry to fund and build four twin-cam quad-valve eight-cylinder racers for the 1919 Indianapolis race. These magnificent machines didn’t conquer the 500-mile event, but established a productive if fractious partnership between the demanding proprietor and the painstaking engineer, which would end badly.

Volume 1 supplies an overview and sees the grand prix cars analysed in huge depth by renowned technical author Karl Ludvigsen, aided by many drawings and photos. That’s a feature of this book; it’s not a straight run-through of company history. Instead it separates into sections by various experts: Ludvigsen on grand prix engines, David Burgess-Wise on the racing cars, including every race by the works team. As well as the bigger 8LC, Ballot built Henry’s exquisite 2LS racing cars, and between them Ballots took second in the 1921 French Grand Prix and won the first Italian GP as well as a range of other race and hillclimb successes, shown in a wealth of fascinating photos. Here Burgess-Wise makes an interesting point, that modern image enhancement now allows us to identify vehicles with “forensic conviction”.

A virtual avalanche of atmospheric pictures fills Volume 2 where all the road cars get their turn, illustrated by factory drawings, period photos, adverts and lavish shots of surviving cars. Bodies by every coachbuilder are shown on frames from the 2LT, simpler cousin of the racing 2LS, to the big straight-eight of 1927 which was hoped to save the firm. It didn’t, but these carried some of the finest examples of grand coachwork on a par with 8-litre Bentleys and HS6 Hispanos. Which is ironic as latterly Ets. Ballot, now minus its founder, began to build H-S engines and install them behind a Hispano-esque radiator, a last attempt at independence before the larger firm swallowed it.

“Of all the people I spoke to only Peter de Paulo had a good word to say about Ernest Ballot”

We’re not done yet: a major section tells of the many cars which used Ballot engines (ever heard of the Bobby-Alba?), plus those boats, airships and traction engines, while nine appendices, including all Ballot patents, confirm how deep today’s researcher probes.

There are two elements of this work that stand out. Yes, the technical presentation is awesomely comprehensive, but there’s a lot to learn about what is called the Ballot legacy. Karl Ludvigsen outlines the influence that the Ernest Henry Ballots had on Harry Miller, on Duesenberg, on Offenhauser and of course on the Sunbeam-Talbot-Darracq combine where, after Henry fell out with Ballot, chief engineer Louis Coatalen would employ him to design the 1922 grand prix Sunbeam. It’s a famously tangled web: as Ludvigsen remarks, Coatalen “had no compunction about stealing and exploiting the ideas of others” and had already copied Henry’s Peugeots for his 1914 TT Sunbeams. Karl also comments that it was the success of Ballot’s masterpieces that encouraged Bugatti to concentrate on an in-line eight layout.

The most revealing part of this work is about Ernest Ballot himself. In photos he has an invariably doleful expression above a prissy moustache (a contrast to the always grinning René Thomas, his team driver, shown in one picture cheerily waving above the charred wreck of his crashed Indycar) and the pen portrait is not endearing. Autocratic and impatient, Ballot had a habit of acting secretly, which probably hastened his end at the helm. That and the poor financial management which became clear once he was ousted in 1927. Cabart quotes historian Griff Borgeson as saying “Of all the people I spoke to only Peter de Paulo [a Ballot team racer] had a good word to say for him”. (Once while eating in a restaurant in Brescia I discovered my neighbour diner was de Paulo’s nephew. If only I’d had more time…)

Possibly fuelled by their uncompromising characters, Ballot and Henry fell out, the book relates, because Henry refused to design the everyday vehicles the firm needed to survive. Sadly Henry’s 1922 Sunbeams proved unreliable and his career slumped. An unfair fate for a genius. But the fact that Ballot then circulated a trade flyer with a cartoon of a shabby, drunken Henry stealing designs from other cars says a great deal about him.

Pity the poor reviewer who tackles a book not knowing enough about the subject to discover gaps or slips… But whether or not there are any (and it’s hard to believe) I found this huge book highly absorbing, impressively presented and convincingly argued. It’s impossible to imagine any Ballot information still out there unfound. And yet…