Barry Sheene's commitment, bravery and trust

Spa-Francorchamps was the world's fastest motorcycle circuit in 1977, when Barry Sheene set an all-time race record

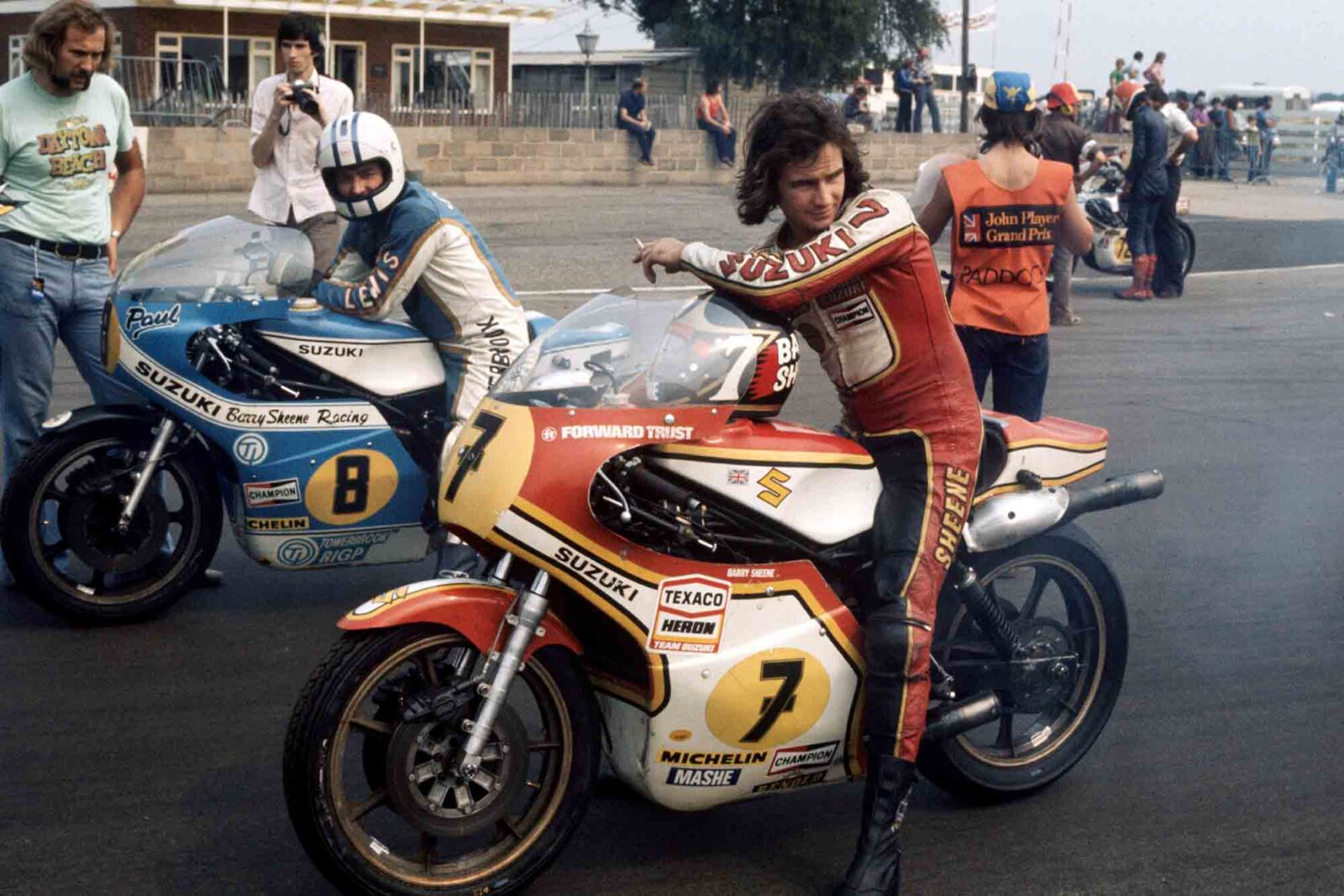

Sheene alongside Paul Smatt at Silverstone in 1976

Motorsport Images

A fickle, fragile 500cc two-stroke with little more than 115 horsepower at the end of the twistgrip and a deadly strip of blacktop sweeping through the Ardennes forest, bordered by rusting steel barriers, farmhouses and herds of dairy cows.

In July 1977, Barry Sheene put the two together and established a record that has never been beaten and will never be beaten. On his way to his second consecutive 500cc world championship, the Londoner won the Belgian Grand Prix at 135.067mph, the fastest ever such motorcycle race. Sheene’s place in the pantheon was secured when the original Spa-Francorchamps circuit was removed from the calendar following the 1978 Belgian GP, putting his record forever out of reach.

Spa had hosted motorcycle Grands Prix since the 1920s, the course winding its way between the villages of Francorchamps, Burneville and Stavelot. In July 1949, Spa claimed the second fatality in world championship racing and by 1977 the road circuit had accounted for several more victims. Only the Isle of Man TT caused more deaths. In the 1960s and 1970s, Grand Prix riders joked darkly that there were so many memorials around Spa that they could make a fence out of them.

Sheene knew all of this when he rode his factory-backed Suzuki RG500 out of the pit lane and up Raidillon to start practice on Friday July 1, 1977. But however much he hated the Isle of Man, he enjoyed the challenge of Spa. Sheene’s loathing for the TT had less to do with the drystone walls and telegraph poles and more to do with the 37¾-mile course that bestowed a huge advantage on older, more experienced riders. He certainly wasn’t scared of anything.

“The big thing about Barry was that he was always ballsy,” remembers mechanic Martin Brookman, who worked with Sheene through much of his Grand Prix career. “I always thought his bravery was probably more than his ability. He was a brave little bastard and just wanted to win.”

As usual, Sheene and his rivals had travelled to Spa from the previous weekend’s Dutch TT, where Sheene had been defeated by local hero Wil Hartog. Thus he needed victory to extend his championship advantage over rookie factory Yamaha rider Steve Baker, who had never ridden a proper road circuit before Spa.

“I went around in my car before practice,” recalls the American. “My first thought was, ‘Oh God, what have I got myself into here?’ It was pretty scary. The thing was that however dangerous it was, you had to keep your corner speed up because, with the 500 engine’s power characteristics, that made a huge difference in lap times.”

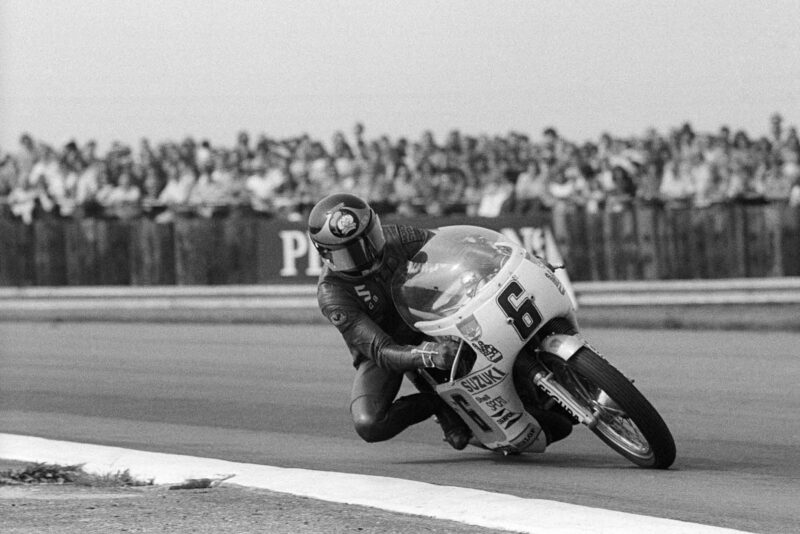

Sheene pushing as usual at Silverstone ’73

Motorsport Images

Another Spa first-timer was Sheene’s new team-mate, Steve Parrish. “I remember riding through that long right-hander through the village of Burneville for the first time, thinking, ‘F**k me, if it goes wrong here… This is just lunacy’,” he remembers.

Sheene was expected to qualify on pole, but didn’t. During the final Saturday afternoon session he was stung by a hornet that had got inside his leathers. By the time he had recovered he had slipped to second fastest, behind Swiss rider Philippe Coulon riding a production version of Sheene’s square-four, rotary-valve RG500.

Worse was to come. After qualifying, Sheene’s crew commenced final preparations for the following day’s race: the usual top-end engine strip-down and a full chassis check-over. They were dismayed to discover a mass of tyre shavings stuck to the centre of the RG’s swingarm. This was bad news because it told them that Sheene’s rear Michelin slick was growing at high speed and chafing against the swingarm. During the 10-lap race there was a good chance the tyre would wear right through and suddenly deflate.

“We had to know that if we lied to him, we could kill him. Simple as that”

Sheene had suffered exactly the same fate two years earlier at Daytona, where his rear Dunlop had popped as he hurtled around the banking at 175mph. In the ensuing accident he broke his left femur, right arm, right collarbone and several vertebrae. At Spa his RG was geared for almost 190mph…

“Barry wasn’t impressed when he saw those bits of rubber – it was a shock because it was, ‘Here we go again’,” says Martyn Ogborne, Sheene’s Suzuki technician. “The problem with the old cross-plies was that they had so much rubber on them that the tyres would grow far too much. So it was, ‘Oh shit, get all the swingarms out, get the grinders out’ and we had to grind the chain adjustment slots so we could pull the wheels right back.”

The following morning Sheene asked Ogborne if the problem had been fixed. “We said, ‘Yeah’, so he said, ‘OK, let’s do it’. It was all done on trust – his mind had to be completely free. We had to know that if we lied to him, we could kill him. Simple as that.”

Sheene prepares to start at Silverstone in 1973

Motorsport Images

Sheene had to work hard in the race. On the first lap he was third, behind Hartog and Parrish. Then French Suzuki privateer Michel Rougerie took over at the front. Like Coulon, Rougerie’s well-fettled production RG was as quick as Sheene’s factory bike. The pair spent several laps together fighting, both breaking the lap record, Sheene upping the pace as he tried to stay with Rougerie, who had eked a half-second advantage by the end of lap six.

A few seconds further back, Parrish was embroiled in an epic battle for third place with 15-times world champion Giacomo Agostini, American Pat Hennen and Finnish privateer Tepi Lansivouri.

“It still stands out in my mind because I’d never slipstreamed so closely in my life,” says Parrish. “You were inches from the other guys, staring at their exhaust pipes. We were doing these ridiculous leapfrogging manoeuvres – you’d slipstream past someone, then he’d come back past you, then you’d go past him again. And you were doing this with your finger on the clutch in case your engine seized, while looking at the other guys’ tail pipes, watching for the tell-tale puff of blue smoke that told you their engine was seizing.”

“Sheene knew he had a mental advantage at Spa”

Which is exactly what happened to Rougerie as he started the final lap, while inches ahead of Sheene, who retained the lead to the chequered flag, despite a misfire. There was no great fuss over the new race and lap records. “Everyone thought we’d go back next year and go even faster,” shrugs Parrish.

They very nearly did. At the 1978 race, Yamaha’s Johnny Cecotto qualified on pole at 138.169mph, but the race was wet, so Sheene’s records remained intact.

Although Sheene enjoyed Spa – “he knew he had a mental advantage there,” adds Ogborne – he and other riders had already started campaigning to have the venue struck from the calendar. The Belgian promoters reacted by announcing the construction of a shorter, safer track for 1979. The current 4.3-mile circuit hosted motorcycle Grands Prix for a decade, until it was likewise deemed too dangerous. The circuit staged its last bike GP in July 1990.