The archives: September 2018

Sixty years after the passing of Peter Collins at the Nürburgring, some reflections on the customs of times past

Unexpected praise is always welcome. I have just had an email from an American collector friend, describing how he and his wife had seen the documentary movie Ferrari: Road to Immortality on which I enjoyed working so much in recent times. They thought it was terrific, but the email ended with this line about racing in the 1950s: “Those were truly different times…”

In terms of driver risk and loss, yes – they most emphatically were different. Front-line racing drivers tended to enjoy brief careers, often punctuated – or indeed ended – by injury and accident. As we run up now to the traditional time of the annual German Grand Prix – at the start of August – it makes my mind spool back 60 years to that frenetic, landmark Formula 1 season of 1958, which ended up by giving Great Britain its first world champion driver – Mike Hawthorn – before taking him away into all-too-brief retirement, following the earlier loss, at the Nürburgring, of his British GP-winning Ferrari team-mate Peter Collins.

The son of the successful Kidderminster motor trader Pat Collins, handsome, personable, popular Peter had become one of the winning quartet of new-generation British racing drivers who were doing so well in that era. Hawthorn and Collins, Moss and Tony Brooks – they all showed the flamboyant skills of early-day Hamiltons, Vettels, Ricciardos and Verstappens… against the background of participation in what was a profoundly risky and perilous sport.

Its dangers could be experienced not just by the star players but by any competitor, of course. Travelling to the Nürburgring Nordschleife to race a Grand Prix car there for the first time could also be a challenging, indeed humbling, experience in the engineering sense.

In 1957 Vanwall had arrived fresh from defeating Ferrari and Maserati so sensationally in the British GP at Aintree, only to find their teardrop cars absolutely all at sea on the humpy, bumpy German ‘green hell’. In 1958 it was the BRM team’s turn to share such an experience with its latest Type 25 2½-litre four-cylinder cars – never having taken them to the Eifel mountain course before.

Mindful of Vanwall’s travails, the Bourne-based team arrived fully armed with alternative stiffer springs, dampers and a multiplicity of bump rubbers. But all proved to no avail during practice as the problem proved to be precisely the same as Vanwall’s in ’57 – a simple lack of wheel travel coupled with blunt lack of experience on the ’Ring.

Jenks wrote in these pages: “BRM would like to have made some unofficial practice earlier but its drivers were not available, so they had to find out, just as Vanwall had last year.” Describing official practice he continued: “BRM was in a sorry state, the cars being off the ground more than they were on it.” The team’s fiery French driver Jean Behra eventually crashed his team-mate Harry Schell’s assigned BRM through the hedge flanking the road near the Karussel. When the mechanics took out the Lodestar transporter to retrieve the car, they drove straight past because the springy hedgerow had closed up behind it, hiding it completely from trackside sight. The mechanics’ initial reaction was that the crowd had nicked their car…

Now one of the greatest joys of researching BRM history is the survival of the highly detailed internal race reports that were provided after each event to company owner Alfred Owen, the intensely committed and devout Christian lay preacher whose beliefs precluded him from attending any Sunday race meeting – which the great continental Grands Prix of course all were…

The 1958 team report for that German GP was written by the Rubery Owen industrial group’s self-confident young engineering director, Peter Spear. He explained how in Behra’s crash the car had ended up impaled on a fencing stake that penetrated the undertray and had one of the chassis cross members resting on top of it. “While that car had to be set aside, on its team sisters the dampers were reset for the second practice and if anything it was reported the conditions were worse.”

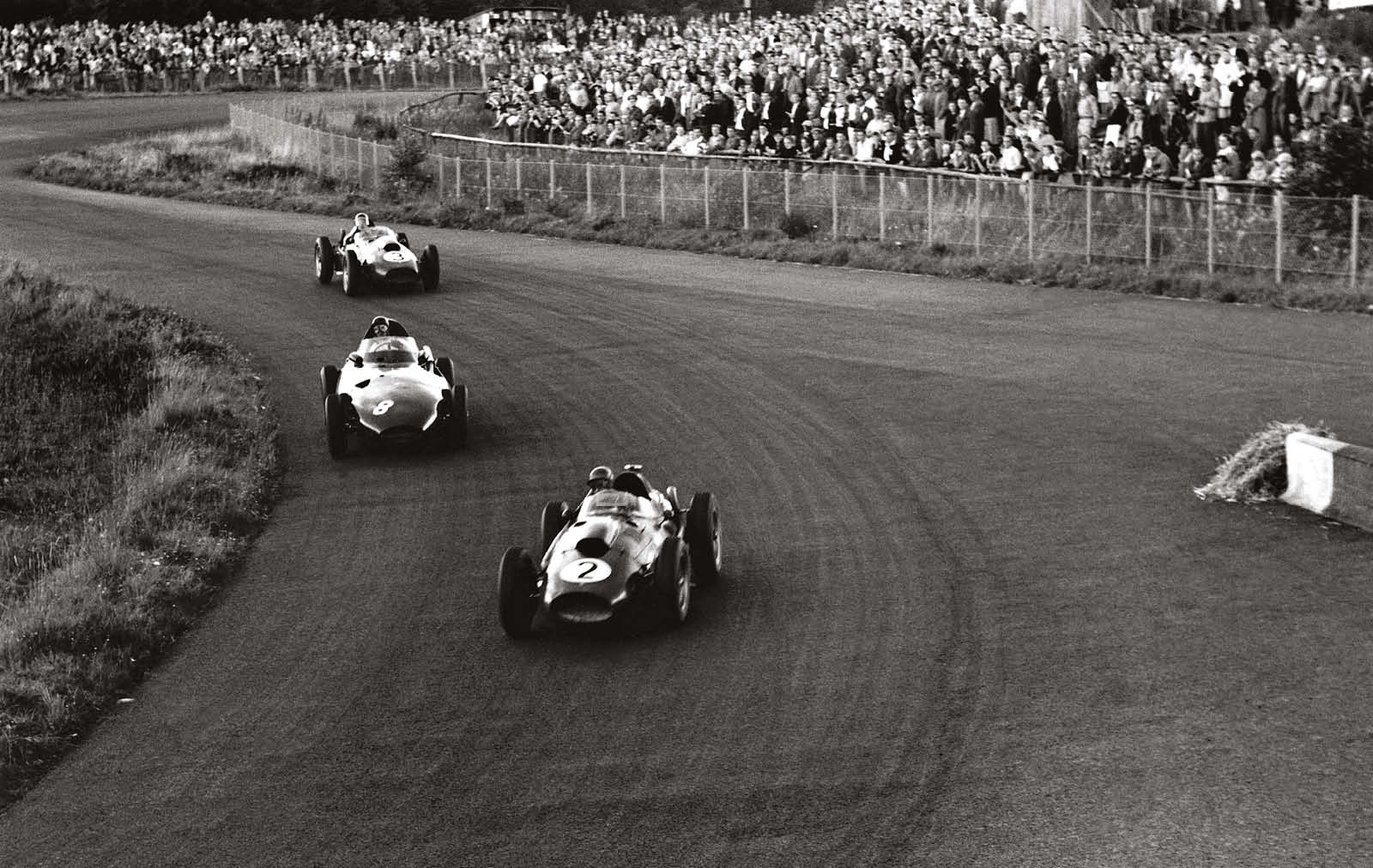

While BRM struggled, the race took off that Sunday with Peter Collins fresh from his British GP win ahead of Hawthorn’s sister Ferrari at Silverstone two weeks before. Here in Germany, Mike qualified on pole from the Vanwalls of Brooks and Moss, with Peter Collins’ Ferrari Dino 246 on the outside of the four-strong front row.

Peter Spear reported: “The race settled down after a few laps with Moss in the lead followed 10sec later by Hawthorn and Collins, who were racing together, changing positions. Brooks was 10sec later followed by Behra…

“In the fifth lap Moss blew up and Behra came in slowly five minutes after the main lot of drivers. He claimed that the car would not hold the road. They worked on the car for a quarter of an hour without success and Behra would not go on” (he felt it was bad for his public image). Harry Schell then retired his team car with brake trouble and, at this point, Spear’s report includes this chilling account of Collins’ death while duelling for the race lead with Tony Brooks’s dominant Vanwall.

“Shortly after this, Collins crashed and Mike Hawthorn came around past the pits driving on the inside of the road not attempting to race. His face was white as parchment. He stopped where Collins had crashed and got out and wanted to go in the helicopter with Collins but eventually went in the ambulance. This left Tony Brooks in the lead…”

Here Jenks reported how, after Moss’s engine failure: “Up in front, the two Ferraris were playing games together, Collins leading across the line at the end of lap six and Hawthorn then taking the lead as they went past the pits. It was now obvious that Brooks was no longer 22sec behind, he was decidedly closer and he did his seventh lap in 9min 16.7sec, which brought him visibly closer to the two Ferraris and on the next lap he was with them, passing on the twisty bits but being overtaken on the fast bits, the Maranello cars having more steam than the Vanwall.

“This was really stirring things up and it seemed a hopeless task for Brooks to do battle against the two Ferraris, but he kept at it and actually forced his way past Hawthorn and into second place as he went into the Nordkurve, making the Ferrari run wide.

“Once again he got by Collins only to be passed again on the straight, but this time he was alongside Hawthorn as they ended the 10th lap, and the Vanwall took the Ferrari as they went into the Südkurve and caught the leading Ferrari as they went into the Nordkurve. Brooks had done his 10th lap in 9min 10.6sec, not as fast as Moss but an excellent time, and now having got the lead at the beginning of the twisty bits he was able to pull away…

“On lap 11 disaster struck the Ferrari team, for rounding the double right-hand curve after Pflanzgarten Collins was in his usual opposite-lock slide when he overcooked it and went off the road in full view of his team-mate, and while striving to catch the flying Brooks.

“Collins was taken to hospital with severe head injuries from which he later died and Hawthorn was left to carry on the struggle, but by the end of that lap his clutch began to show signs of failing and as the Ferrari went up the return road behind the pits it suddenly slowed and though Hawthorn continued on lap 12 he did not reappear.

“This little scrap that ended so tragically had been motor racing at its best and the three of them had completely outpaced the remainder of the runners so that when Brooks went by on his own at the end of the 12th lap he was nearly 3min ahead of Salvadori, who was in second position (in the Cooper)…”

Times were changing – and dazzlingly fast. This was a formative event for me as a 12-year-old schoolboy fan, starry-eyed by racing cars and drivers of each and every hue and nationality… but particularly so by the Brits – it was natural then. But the death of Collins was a stunning blow – as much to the enthusiast fraternity as to those who knew, liked, admired and worked with him. Yet within the customs and practices of the period nobody other than his devastated young widow Louise, immediate family and closest friends – led by Mike Hawthorn, of course – really dwelt upon it. Death was a natural travelling companion of all front-line racing drivers in that era – the sobering and ever-present penalty for less than perfect performance. Today making a small positional error, or suffering a braking and damping deficit – as Collins did – while still pressing near maximum effort, could inflict this terrible cost.

No trackside run-off areas, long-grassed sloping roadside banks, stout trees ever-present like cricket fielders poised to catch the ejected, airborne hapless human – the helpless, far-flung motor racing superstar. And in an instant he and the British Grand Prix community had lost all he had ever experienced, and all he would ever experience. Finality – on a sporting Sunday. But that – as my movie-viewing American friend put it – was simply typical of those “very different times”.

Raise a glass to the great British boys’ stupendous talents in those times. Their modern-day counterparts, heirs ands successors should be truly proud of them – heroes all. Again back to Jenks – one of whose favourite sayings was simply “Aah nostalgia – the real thing.” He’d been there. He’d seen it first-hand. He knew.

Doug Nye is the UK’s most eminent motor racing historian and has been writing authoritatively about the sport since the 1960