Lunch with Anthony Reid

Having cleaned the oil rig toilets to raise funds for racing, he went on to win the Japanese F3 title and the hearts of the British motor sport public

Lyndon McNeil

It’s Sunday at Goodwood’s Festival of Speed and Anthony Reid heads up the hill at the wheel of an Arrinera Hussarya GT3, an obscure Corvette-powered Polish supercar he has spent much of the winter trying to develop into a credible racer. Tackling the course with customary verve, he wrestles it across the line in 48.23sec, more than 2sec quicker than anyone else so far.

But now come the others: Mike Skinner in his 800bhp Toyota Tundra NASCAR pick-up truck, four times British Rallycross champion Pat Doran in his Ford RS200, Paul Dallenbach in his 900bhp Pikes Peak special, Andy Newall in his 800bhp McLaren M8F and James Grint in his Mitsubishi Mirage. One after the other they attack Reid’s time in cars with either far more power or far better suited to the hill. Or both. But of greatest interest is Reid’s reaction as in turn they fail to match his time. It starts with a single index finger to the camera to indicate he’s still in first place. Then there’s a fist pump, then hands raised above his head. As the number of remaining competitors is reduced to a handful, Reid literally leaps in the air. And when Mark Higgins’ Subaru Impreza finally goes 0.03sec faster, Reid briefly looks desolate. You can argue all day about whether it should or not, but you cannot question that, to Anthony, this stuff still really matters – despite all he’s achieved in 40 seasons of racing,

Wind back a couple of weeks and we meet in the rather less frenetic surroundings of Reid’s favourite pub, the Prince of Wales in Iffley, Oxfordshire, where he lives. Reid is something of a local hero and the walls are covered in pictures of him with his racing buddies who’ve come to drink with him and reminisce in here.

Anthony, who has the air of someone who has never been late for anything, is already there and engrossed in conversation with the owners and sundry other regulars, a bottle of house champagne already on the go. He is dressed in jeans, but wearing a colourful blue check sports jacket topped off by a Panama hat. Unlike most ‘Lunch with…’ subjects, Anthony has brought a guest in the form of Jack, a rather elderly terrier. Jack is as well known within these walls as his owner, so while Anthony and I sit down and start the tapes rolling, Jack hangs out with the locals.

A sideways Reid’s PRS battles fellow Scot Tom Brown’s Van DIemen in the 1979 Brands Hatch Formula Ford Festival

Motorsport Images

He starts with a Cajun-spiced chicken Caesar salad as his tale begins in Glasgow, where Reid was born 60 years ago. “I wasn’t part of a racing dynasty, but we had friends who were into cars and my father was certainly interested, I distinctly remember him switching from Hillmans to Fords because the GT40s locked out the podium at Le Mans in 1966.

“Crucially my Uncle Norman – Norman Barclay – had not only raced Formula Libre against the likes of Jim Clark and Jackie Stewart, but was mates with Keith Schellenberg with whom he tried to do the 1968 London to Sydney in an 8-litre vintage Bentley. Despite being kidnapped by bandits in Turkey and rescued by the local prince, I think they made it as far as India. Growing up on such tales, how could I have become an accountant?”

If that wasn’t enough, the young Reid was soon to have another profound racing influence. “In 1970 I was sent to Loretto School outside Edinburgh, which is where Jim Clark had gone. Although he’d died a couple of years earlier, he was still a complete hero there. Bored to death during the headmaster’s sermons, I’d just sit and gaze at this massive wall plaque honouring him. I’d read ‘twice world champion’ and dream of racing. That’s what made me want to become a racing driver. Problem was, I had no money.” This is a theme to which we shall be returning.

Lacking the means did not stop him from racing. Somehow he scraped enough to attend the Jim Russell Racing School at the end of 1976 and had a shot at the International Scholarship. “The judges were Derek Bell, Jack Sears and Alan Henry and they awarded me the big prize: a free season in the 1978 Esso Formula Ford championship. It was a well-respected series and for someone with no money – my father was an architect working for Glasgow City Council – it was a fantastic break. But all through my youth I had to duck and dive to go racing. I was never a member of the lucky sperm club.”

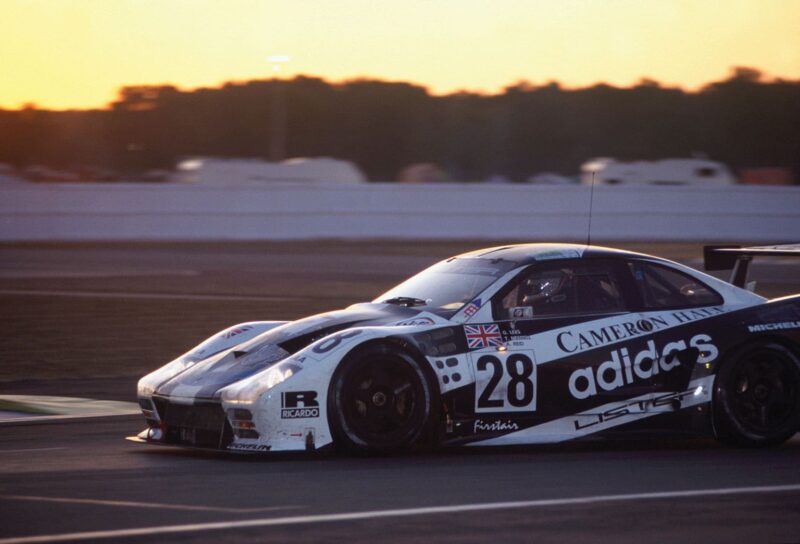

Driving for Lister at Le Mans in 1996

Motorsport Images

So Reid had to work. “I had a grandmother who lived in Caterham so I wrote to Graham Nearn, got a job at Caterham Cars and lived with her while building Super Sevens. It was an incredibly valuable experience, because it gave me a grounding in how cars work. I knew how to set them up, what was wrong with them and how to fix them, but it also saved me a fortune because I could work on my own racing cars. Even now when I feel things that are not quite right, my ability to diagnose a problem goes straight back to my time at Caterham.”

Reid worked at Caterham during 1976 and 1977 and then went to work for Jim Russell during the free season that he’d won. But the season was not a success. “I think I got a second place once, but it was so unbelievably competitive. You’d get 140 entries for a race weekend so just making the final was an achievement. But it came to nothing and I ended up with no more racing to do and no money to do it with.”

He got another job, this time at Image Racing which built Formula Fords in the Super Shell building at Goodwood. “Alan Langridge was the boss and the deal was I’d work on the cars all week, and race them at weekends. Don’t tell Lord March but I lived in a caravan around the back and, when we wanted to go testing, we just pushed the car through a gap in the fence. No marshals, no medics, no anything. I once crashed at Madgwick and it was 10 minutes before anyone realised I’d gone missing. The track was great but the safety non-existent. But I crashed too much and they fired me.” Reid was unemployed and broke once more.

“At the start of 1979 I had nothing. Literally nothing. But then an old friend told me there was money to be earned in the oil business in Scotland. So we presented ourselves to the Sullom Voe Oil Terminal in the Shetlands and got jobs the next day. I was a toilet cleaner.”

The only good thing about cleaning the loos in the oil workers’ accommodation blocks was that the work was so awful it had to pay well, albeit not quite well enough. So Reid took a night job driving taxis and lived in a tent. “Sounds like madness, doesn’t it?” he says, a view I feel disinclined to challenge. “Also, as you can imagine the weather up there can be quite challenging at times for tent dwellers. A mate and I had an old Vango Force Ten that had been stored damp. On the first night we went to the pub because we knew there was no way we’d get any sleep sober. I woke up outside in the middle of a raging blizzard. The tent had just gone.”

Yet Reid recalls these as immensely happy times. “Having been brought up in Scottish boarding schools, I was used to the cold. We’d had no central heating, we used to chip the ice off the inside of the windows and at prep school were forced to use an unheated outdoor pool. You couldn’t see the bottom it was so full of plankton and oil from Grangemouth.”

Leading Matt Neal and James Thompson at Oulton Park BTCC in 2000

Motorsport Images

Reid’s skills both as a driver and cleaner of washroom facilities were honed at Sullom Voe. “My wife’s still amazed at what I can do with a bottle of bleach, but I quickly became known as the fastest taxi driver on the island. Oil workers used to ask for me personally to get them from one pub to the next before closing time. In return I’d get double fares. And because I had a shit day job they had to pay really well; with all my taxi money and living in a tent, within three months I’d earned enough to buy a racing car

“So I kept coming down from Scotland, racing, crashing as you do when you’re young and stupid, and then the bank manager would ring up and tell me to go back to Sullom Voe. After a while I was promoted to building houses, still driving taxis and upgraded my accommodation to a beaten-up caravan just to stave off frostbite.” Even now the big break seemed as far away as ever. But at the end of 1981 he finished 10th in the Formula Ford Festival, having run as high as seventh in the final. And now a door opened, just an inch or two.

“My old racing school head coach John Kirkpatrick was putting a team together for the following year. If I could raise a bit of money he said I could drive for him and he’d make up the difference. I managed to raise £4000 from an uncle who had small pharmaceutical business, which funded me in 1982 in Formula Ford 1600, and in 1983/84 in FF2000 with a JK Racing Argo JM14, when I had a team-mate called Damon Hill…

“For the Winter Series at Brands we were on BBC1 Grandstand with Murray Walker and Tiff Needell commentating. We had sponsorship from Linn Hi-Fi, the team owner pumped in a lot of money and suddenly I was winning races. I don’t think I knew it at the time, but it was the turning point of my career.”

By then he was not just racing with Damon but against other former ‘Lunch with…’ subjects such as Martin Donnelly, Julian Bailey and Perry McCarthy. “I’d grown up enough to have worked out how not to crash and realised I had the ability to compete against the best. That’s where the belief came from.” But not the money.

Podium finish at Le Mans in 1990 was a major breakthrough

Motorsport Images

“Then a bloke from the team called Bob Moore, probably the best salesman I’ve ever come across, persuaded Saab to put together a Formula 3 programme for 1985 and this became the Saab Scan Sport team. Saab had no intention of going racing, and had no interest in getting involved in motor sport: Saab did rallying. But Bob somehow talked them into it, got the money, put the team together with Madgwick Motorsport, had a big launch in a London hotel and I thought I’d made it. It didn’t take long to realise how wrong I was.

“It was only at the end of the season when I drove a Dave Price Reynard with a VW engine that I realised just what a boat anchor we had in the back of ours. The Saab motor was not just heavy, it lacked power and if it rained the water would crash the engine management.”

It rained at the first round at Silverstone and, even with sponges stuffed into the air intakes, Anthony knew he had three laps in which to qualify before the water got into the engine. “Coming into Woodcote I found three cars hidden in the spray going incredibly slowly. I missed the first, clipped the second and cartwheeled over the third. It was the best publicity Saab had all year.

“The season didn’t start well, it didn’t get any better and right at the end it got really, really bad.” By the Snetterton round he and usual team-mate Maurizio Sandro Sala had been joined by Bailey. “Bob Moore told Saab everything was about to turn around so they put up a big hospitality tent on the inside of Riches. Maurizio was on one row, me on the next and Julian on the row behind. The flag dropped, we rocketed off to Riches, Julian hit the back of my car, I hit the back of Maurizio and all three of us crashed in front of 200 Saab VIP guests at the first corner.”

That was that. Saab gave up, Reid lost his drive and ended up back again at square one. “It was a bit galling,” he says with considerable understatement. “But at that level you need money and I didn’t have any.”

That year Reid shared the Alpha Porsche 962C with fellow Bits Tiff Needell and David Sears

Motorsport Images

Anthony entered his wilderness years, working for the next three seasons as an instructor, doing some club races, watching his dream of reaching the top of his chosen profession disappear. But in racing the darkest hour is often that before the dawn. In 1989 he found himself driving a Vauxhall Lotus for Peter Thompson Motorsport in a support race for the British Grand Prix. And with the eyes of the racing world upon him, he won.

The result was an invitation from Convector team manager Bo Strandell to test a Porsche 962 at Monza. “This thing had 800bhp when the most powerful car I’d ever raced had about 170. Back then an F3 car would stop accelerating at 120mph – the 962 was still pulling like a train at 200. But it didn’t bother me: I’d spent all my racing life jumping into different cars. I just got on with it.”

And got signed. He did the first three races of the 1990 season, sharing with Eje Elgh and Jürgen Barth and “still crazy enough to think I could get to F1.” But there was no money to do Le Mans. “Then, two weeks before the race, Tiff rang to say there was a seat free in the Kremer entry he was driving for the Japanese Alpha team.

“So the next thing I know I’m at Le Mans doing 220mph. This was my first 24-hour race and the scale, the speed and danger were a total assault on my senses. Tiff, David Sears and I didn’t qualify well, but we came through the field and finished third behind the factory Jaguars, the last time a 962 would be on the podium at Le Mans. It was the dream race. It was a hot year, we had no power steering or air-conditioning and I was recovering from food poisoning, but none of us put a foot wrong.”

Le Mans 1990 turned Anthony Reid’s life around and, for the first time in a dozen years of racing, he’d actually been paid. “Twelve grand for a weekend’s work seemed like pretty good money to me and it meant I was at last a professional racing driver. But of course the real significance was that it got me to Japan.”

Reid would spend the next six seasons over there, but he still had one appointment left in Europe. “Convector asked me to do the last Interserie round at Zeltweg. By then we had an Andial engine with 850bhp and my main opposition was Bernd Schneider in a Kremer Porsche. He beat me in the first race, but I overtook him in the second, won and took the overall victory. Schneider turned up late for the podium wearing jeans, they couldn’t even find the national anthem. They’d never expected a Brit to win.”

Reid was part of Mg Sport & Racing line-up at Le Mans 2001, and here in 2002

Motorsport Images

In Japan Reid finally found a way to earn a proper living doing what he loved. “There was a huge contingent of European and US drivers out there. I did Group C, F3, F3000, Group A, anything I could get my hands on. I stayed because the money was tremendous and the pioneers who’d set up the racing scene out there, like Tiff and Geoff Lees, told me how it worked. You had to get your job on merit, but once it was yours no one would try to steal it from you. We adhered to a pay structure that made sure we weren’t undercutting each other. You’d get rich drivers coming over with big budgets and we’d tell them that in Japan you don’t pay to race, you get paid. The Japanese generally won’t meet with anyone unless via a trusted third party, so these guys didn’t know who to speak to, their money was useless so they just got the next flight home. And the money was good: I remember Eddie Irvine complaining about the pay cut he’d have to take to leave Japan to race in F1 for Jordan.”

It was also Japan that brought Reid closest to realising his F1 dream. “I’d met a Japanese property developer who wanted to sponsor me in F1, so I met Eddie Jordan at the old factory at Silverstone and he sent me a letter saying the drive was mine if I could raise £2.5 million. Two weeks before contracts were signed, the Japanese bubble burst, the sponsor went bust and that was that. I still have the letter framed in the downstairs loo.”

But Reid was nowhere near done with single seaters and, in 1992, won the Japanese Formula 3 title. Jacques Villeneuve and Tom Kristensen were second and third that season, which underlines the magnitude of that achievement. “I found myself under the impression I was a bit of a hero and still had half an eye on F1. I got a test in an F3000 car at Fuji a few days after I won the title.

“The truth is I went out to prove a point and just overcooked it. There’s a corner called 100R which was flat, but only if everything was perfect. But there was no run-off, just a layer of tyres and a concrete wall. I got into a tank-slapper at 160mph and hit the wall so hard my helmet just peeled off my head. The car shot 25 feet up in the air and turned upside down; Roland Ratzenberger had to swerve to avoid being crushed as it came down. The roll hoop immediately snapped off, but because it was a Lola it had a high back to the tub and I had a low driving position so my head ended up just skimming the road at 160mph. When the dust settled, there was a lot of blood on the track and the marshals just assumed I was dead. It was Roland who organised the ambulance, got me out of the car and off to hospital. When he was killed at Imola 18 months later I wrote to his parents to tell them what he’d done for me because I was sure they wouldn’t have known. When you race cars, the line between life and death can be very thin.”

Reid and Rickard Rydell vie for position at Brands Hatch 1998 BTCC

Motorsport Images

Reid was in hospital with severe concussion for five days, but was soon back in his F3 car at Suzuka. “Really I shouldn’t have been allowed anywhere near it. My vision was swirling in left-handers, but I realised that at Suzuka all the left-hand turns were flat in an F3 car, so I just braced myself, set the steering angle and closed my eyes…”

after a fruitless partial F3000 season in 1993, Reid was introduced to the touring car racing in which he’d make his name. Driving a Vauxhall Cavalier for HKS in the Japanese Supertouring Championship, Anthony had a successful couple of years and, while he missed the title both times, he did well enough to attract the attention of Nissan, who signed him to race in Germany from 1995 before he made his debut in the BTCC in 1997.

“Nissan came to the BTCC at its zenith. Remember there weren’t 500 TV channels back then and we were on BBC1 Grandstand with Steve Rider presenting, Murray commentating and all the big names like John Cleland, Alain Menu, Rickard Rydell and F1 drivers like Derek Warwick and Gabriele Tarquini. And the crowds were huge. Only looking back do you realise the significance: we had more pro drivers in the BTCC than in F1. It was a brilliant time, and it allowed me to buy a house in the village of my favourite pub.” This pub, needless to say.

Reid spent a difficult 1997 with an undeveloped Primera, but once RML got the car properly on song he scored the most poles and won the most races in 1998, but finished as championship runner-up to Rickard Rydell. Then he went to Prodrive and Ford and had a repeat performance, one year spent getting the Mondeo race-ready, the next in the thick of the title fight to the last round. Ford took a BTCC clean sweep, but Reid was again second – this time to Alain Menu.

It was during this time that Reid became known for his somewhat uncompromising driving style and the many and various confrontations with other drivers that resulted. Today, he is entirely unrepentant. “I think the only person with whom I didn’t have a punch-up was Jason Plato,” he says, I suspect only partly in jest. “But it was part and parcel of the show and why it made such great television. Remember when Rickard Rydell tried to strangle me live on air? You can’t say that didn’t make good viewing. It didn’t bother me at all; to me it was fun and it went with the territory. And I wasn’t the only one: look at Cleland, Soper, Plato and Matt Neal.”

Reid’s MG ZS kicks up the Mondello Park dirt in the 2003 BTCC

Motorsport Images

Surely there were some regrets? Reid falls briefly silent. “These days I sometimes think there were perhaps times when I did try too hard.” I ask him to elaborate. “In certain key moments I tried to drive too fast, hurt my qualifying position and just missed out the title. But the aggro? No, I don’t regret that at all.”

By the end of 2000 Supertourers had priced themselves out of the BTCC and a new era of touring car racing, more closely resembling showroom models, began. As one of the most successful drivers Reid was in demand, and chose to join MG because its offer came with a sizeable additional carrot.

“I know I’m best known for touring cars, but sports cars were always my first love and the chance to race for MG in the BTCC and also at Le Mans was too good to pass up.” The MG-Lola EX257 was designed to compete in the LMP675 category for ultra-light prototypes. “It was brilliant to drive, but the 2-litre AER engine was producing 550bhp and was not sufficiently reliable.”

In the first year both cars retired early and even in 2002 Reid knew its time in the race would be limited. “I said to [team-mates] Jonny Kane and Warren Hughes, ‘We could drive around at 5mph for next 24 hours and the car will still break, so let’s thrash its arse off instead.’ Which is what we did, and we got it up into third place, splitting the factory Audis. I remember being in the car just before midnight when Tom Kristensen came out of pits several hundred metres ahead of me. I caught him up during the stint and was annoying the hell out of him, swerving around coming into Arnage with lights on full blaze – later he told me he got on the radio and asked who the f*** it was. We’d had titanic battles in F3 and Japanese touring cars – and I’m not sure he could quite believe it. Then a 50p component broke in the gearbox and we retired on the spot but with heads held high. Far rather that than the walking wounded, 19 laps down at 10.00am with hours still to go.’

Meanwhile Lola was also building the MG ZS touring car, the first such car it had engineered. “We only entered the last three race weekends in 2001. Vauxhall had had no opposition all year and was on the grid with all its trophies, just assuming it was going to win. Halfway through the race the heavens opened and while everyone dived in for wets I told Dick [Bennetts, West Surrey Racing boss] I was going to stick it out. I lapped the entire field before they started catching me again, but the race was red-flagged and I won.”

Reid raced on with MG in the BTCC through 2002 and 2003, doing well but not well enough to challenge for the title. And then, when MG Rover started to implode, he and Bennetts found the money to continue as a private entry in 2004. “We won the Independents Cup but if MG had stayed on board it could have been very different. The car’s biggest problem was its heavy V6, but John Judd found a way of expanding Rover’s tiny lightweight four-cylinder engine from 1.4 to 2.0 litres. Suddenly we had a car that was lighter, with better weight distribution and didn’t eat its front tyres. With MG sponsorship we could have won.”

Just about the last event of Reid’s front-line touring car career was the one-off Masters race at Donington in 2004. Sixteen great BTCC drivers lined up in identical Seat Leon Cupra Rs and Reid won. He may never have won the title but, on the only occasion the playing field was genuinely even, he beat Menu, Tarquini, Biela, Cleland and Neal in that order. It was, he says, “not a bad way to sign off.”

After that Reid did some more touring car racing in Argentina, but having had an invitation to the Goodwood Revival in 2001 had developed a great love of and aptitude for historic racing. “I’ve been very lucky to do all the big classic races, like the Revival, Le Mans Classic, Spa Six Hours and so on, and I’ve driven some pretty amazing machinery too. I remember driving the Jaguar D-type that has the identity of the 1955 Le Mans winner, having to use the full width of the track and slide it through the kinks thinking ‘This is what Mike Hawthorn did, this is heaven’.”

But Reid’s nostalgia only goes so far. Ask him whether he’d rather drive an old classic or a state-of-the-art modern bolted to the track with slicks and downforce and he will look you in the eye and say, “Whichever has the better chance of winning.”

Then again, ask him to name the most exciting car he’s ever raced and without pause he says, “Ludovic Caron’s Shelby Cobra. It’s brutally quick, light, and from the moment you enter Madgwick to the moment you exit the chicane, you are in a permanent four-wheel powerslide. It’s a beast, it’s crude, it’s aggressive: it’s orgasmic to drive.”

Today Reid races on and is part of the team challenging for the Fun Cup title for cars that look like old VW Beetles but are in fact mid-engined single seaters with silhouette bodywork attracting some serious teams with some proper drivers. And, of course, he still races historics wherever and whenever possible.

It would be tempting to see the career of Anthony Reid as those of so many other talented racing drivers whose talent isn’t reflected in trophies. If only he’d had the money, if only he’d had the breaks, if only, if only… It’s an attitude for which Reid has little time: “I’ve had and am still having the most fantastic career. I feel incredibly lucky to have been racing for 40 seasons, not always in the safest circumstances, and still to be here in good health, enjoying the business.”

As you talk about the past he seems relaxed. But mention the future, even a run up Lord March’s drive in a Polish supercar, and a spark returns to his eyes. Even now, with nothing left to prove, the fire still burns. For a man who is one of the most ferocious competitors I have ever met, I suspect it always will.