Lunch with... Emanuele Pirro

Le Mans left him cold after first he’d competed there, but it went on to play a pivotal part in one of modern racing’s most successful careers

James Mitchell

Motor racing is about much more than statistics; but in almost any driver’s CV there will be a statistic that points to the hallmark of his or her career. In Emanuele Pirro’s case, it’s not so much that he won the Le Mans 24 Hours five times – a total beaten only by his frequent team-mate Tom Kristensen and by Jacky Ickx, and the same number as Derek Bell and another team-mate, Frank Biela. It is more that he stood on the Le Mans podium nine times consecutively. That record will probably never be equalled.

And this is someone who for a long time saw himself purely as a single-seater racer. But his Formula 1 career, as things turned out, was confined to half a season in a top team, when it was going through a thin patch; and two seasons with an underfunded little outfit that was never going to move far off the back of the grid. But if you run through the roster of Emanuele’s victories, not just in world championship endurance rounds but in ALMS, international touring cars, Formula 3000, the Japanese Grand Champion category and now historic racing, you appreciate that here is a versatile racer whose 28-year professional career was truly successful.

Motor racing has been good to him, yet he is totally unflamboyant. His connections with Ingolstadt mean he drives a sober Audi saloon. Others may wear a £20,000 watch and a gold bracelet, but he has a few quid’s worth of black plastic on one wrist – “it tells me the time, accurately” – and on the other a rubber Goodwood driver’s band, to remind him of the fun he had at the Members’ meeting last March (co-driving Shaun Lynn’s Cobra, he won the Graham Hill Trophy race).

But he does live in a glorious house, on a private estate 20 miles north of Rome. It was built to his specification 19 years ago, and the big, airy rooms on differing levels flow into one another. The main sitting room displays no self-indulgent racing pictures, and no winners’ silverware – except that on a shelf at one end, unobtrusively, are five identical examples of the comparatively undramatic trophy you get from the Automobile Club de l’Ouest if you win its 24-hour race.

Pau F3 1985: Pirro leads away from pole. He eventually finished second to Christian Danner

Motorsport Images

However, hidden in the basement is a fully equipped gym, and away from visitors’ eyes the walls are lined with dazzling trophies, plus all the crash helmets he wore in his long career. Next to it is a little workshop full of tiny tools and paint pots. This is where he finds time to make superbly detailed models of the racing cars since the beginning of motor sport that have caught his imagination.

Emanuele likes to cook. When I asked him to choose his favourite restaurant in Rome so that I could buy him lunch, he wouldn’t hear of it. Instead he insisted that photographer James and I should join him and his beautiful Belgian wife Marlene for lunch prepared by him in his own kitchen. So our interview continues among the saucepans and dishes, Emanuele talking volubly about the different stages of his career as he dances between hob and chopping board.

We eat on a tiled verandah overlooking the swimming pool, and he provides a starter of linguine with shrimps, followed by sea bass baked inside a thick coating of unrefined sea salt. When it comes out of the oven the salt is discarded, leaving the fish moist and with a delicate flavour. Palate-cleansing canteloupe melon completes a memorable meal.

Emanuele was born in 1962, not into moneyed opportunity but into an ordinary family that happened to love motor racing.

His father had an electrical store, but managed to compete in the Mille Miglia in his Fiat 600. He drove it from Rome north to the start in Brescia, did the thousand miles, and drove home again. At nine years old Emanuele found an ancient baby Fiat for himself, brush-painted it black, and under this camouflage drove it on the back roads at night. His hero Jochen Rindt had already been killed at Monza, but he dreamed of F1. “I knew it was impossible, like dreaming I’d become the President of the United States. Then one night I saw a falling star, and I stood there and wished: I want to be a racing driver.”

In ETCC action at Donington in 1986

Motorsport Images

He got his father to pay for more and more hire sessions at a local kart track, until dad decided it would be cheaper to buy him a kart of his own. Once old enough to race he was marked out as a talent to watch, and soon he had attracted enough backing to fight at the top level. At 14 he was Italian kart champion, going on to finish second in both the world and European championships.

“Because of the karters in Italy who went on to do well in cars – Patrese, de Angelis, Cheever, de Cesaris – karting was thought to be a good talent pool. In 1980 Fiat backed a new single-seater starter category, Formula Fiat Abarth, and somehow my father borrowed enough money for me to do it. I was picked up by a team called Scuderia del Grifone, who rallied for Lancia with a Stratos, and I found out later that the Lancia competitions boss, Cesare Fiorio, had suggested they run me. We shared all the costs and the prize money, which was quite good. And I won the championship.

“That brought me some publicity, and Fiorio invited me to drive a Jolly Club Lancia Montecarlo turbo in the Daytona 24 Hours in 1981. I was 19, and all I’d done was short Italian races in the little Fiat-Abarths. Now I was doing a 24-hour race in another continent. That thing had over 400 horsepower, and when I got in it, it felt so fast. The team got me to start the race, with the idea that when the Jolly Club turbo Ferrari of Carlo Facetti and Martino Finotti blew up – as it duly did – they could take over the Lancia. So all three of us drove it. It was not the racing I knew: up on the banking in all that traffic, with the Porsche 935s of Brian Redman and Derek Bell coming through. Well, we finished fifth overall, and more important we won the 2-litre GT category to give Lancia maximum World Endurance Championship points.

“After that Fiorio decided to run me at Le Mans in one of the works Lancias, sharing with Beppe Gabbiani. I took over from Beppe for my first stint, and on my first flying lap I saw a terrible accident at the Mulsanne kink.” Flat out, Thierry Boutsen’s WM had a suspension failure. “One marshal was killed, two more were injured, Boutsen survived. Driving behind the pace car you had time to think about it.

“An hour later there was a repeat, again on the Mulsanne Straight. It was Jean-Louis Lafosse’s Rondeau, and I tell you, when a car goes into the trees at more than 210mph you don’t want to see it. Wreckage was scattered for more than 200 yards, and Lafosse was dead. Behind the pace car again, we had to pass the wreck lap after lap. It was a real shock to me.

Pirro leads at Monza during 1987 World Touring Car round

Motorsport Images

“After that a sad atmosphere hung over the event. I finished my stint, Beppe took over, and I was putting on my helmet for my next stint when Beppe went overdue. There was no TV then, communications were difficult, but we heard there had been another big accident on the Mulsanne Straight involving our Lancia and another car. [Jean-Daniel Raulet’s WM had collided with Gabbiani.] Then it filtered back to us that Beppe had been killed. I said to myself then, I will never, ever come back to this place. Not as long as I live.

“Then, to our massive relief, Beppe arrived in the pits on foot. He and I decided we didn’t want to stay a moment longer so we jumped into my VW Polo and drove off into the night.

I drove Beppe to Paris, dropped him at the airport and then turned around and drove without stopping back to Rome. You know how in France, as you leave a town, you see the town name on a sign with a red line through it? I saw that sign driving out of Le Mans, and I thought, ‘That is the last time I will see you.’

I couldn’t have guessed what a part Le Mans would play in my life, 20 years later.

“I also did the Kyalami Nine Hours that year, with Michele Alboreto. We won that outright. I’m not one of those people who say nice things about someone just because he is dead, whether I liked him or not. Dying doesn’t mean you win a voucher that says everyone has to be nice about you. But Michele was a special guy, and I had a lot of respect for him. He came from a modest family, his father was a concierge, but he was a real gentleman. He had learned so much about life: he was one of the people, along with Dindo Capello, who taught me the most. He was at the end of his career when he was killed [in an Audi test at the Lausitzring in 2001, when a tyre blew]. He was doing endurance racing as a bonus. His career was almost over, so his risks should have been over. It was a bit like Senna: because of his incredible ability, you never thought Senna could die.”

During 1981 Emanuele was also doing Formula 3 for a small team on a costs-only basis, and won the season’s final race at Mugello. This helped him to a seat in the Euroracing team, and second place in the 1982 European F3 Championship. By 1984 he was in Formula 2 with Mike Earle’s Bognor Regis-based Onyx team, and had moved to London, living with a couple of Italian friends.

F2 was dominated that season by the Ralts of Mike Thackwell and Roberto Moreno with their works Honda V6 engines. “But my March-BMW 842 was a very good car. If you ask me to name the three best cars I drove in my career, I would say, in their day, the March 842, the McLaren MP4/4 F1 car and the Audi R8. As for Mike Thackwell, he was one of the most talented drivers I ever came across. He had God-given ability, but his character did not match it. We did the Macau Grand Prix, which was for F3 cars that year, and in the post-race press conference he said, ‘I don’t like Formula 1. It’s too safe, and the drivers are paid too much.’ I really think he meant it.

In 1989 Benetton chose Pirro to replace Johnny Herbert from mid-season

Motorsport Images

“In 1985 Formula 3000 started, and Mike Earle moved me into that with a March 85B.

It was the beginning of the flat-bottom era, but the March was a wing car. The engine [a Mader-prepared DFV] was big and bulky, and at first the car was not very nice to drive. It took a while to find a nice set-up.” Nevertheless Emanuele won two of the first five races, and led more laps during the season than any other driver. “But I lost a bit of focus. It started when Mike Earle called me and said, ‘Good news for you, bad news for me. Bernie Ecclestone just called and asked for your number.’

“I stood by the phone, practising how to say ‘Hello’ in the best way. The phone rang, and the voice said, ‘This is Bernard Ecclestone.’ He didn’t call himself Bernie, he said Bernard.

‘I want to talk to you. When can you get here?’ I had already worked out exactly how long it would take to get from my flat to Chessington, so I said, ‘I’ll be there in 36 minutes.’

“The Brabham number two to Nelson Piquet that season was François Hesnault, and after four races, with one crash and one DNQ, Bernie had decided to replace him. I walked into his office, very nervous, but he was friendly and charming. He told me he wanted to give me the No 2 Brabham drive for the rest of the season, and said: ‘Do you think you’re ready for Formula 1?’ He wasn’t offering me a test first, he was going to put me straight in for the next race, Montréal, and then around the streets of Detroit, not the easiest tracks to start with. And those turbo F1 cars were really wild.

I said, ‘Well, Mr Ecclestone, the honest answer is I don’t know, because I have never driven an F1 car. I can only try to do my best.’ Of course what I should have said is, ‘Of course I’m ready. It’s just a car with four wheels and an engine.’ But he said, ‘Fine. OK, go into the workshop and get a seat made.’

“In fact I did get to try the car, because Olivetti, one of the sponsors, wanted to do some filming. I did a few laps at Silverstone and a few practice starts, and that was all fine. As I was getting ready to fly to North America, Bernie called again. ‘Emanuele, I need to ask you a favour. Our results haven’t been great this season and our relationship with [engine supplier] BMW isn’t that good. They want us to put their driver Marc Surer in, just for a couple of races, and I want to keep them happy. So you can start with us the next race after that, Paul Ricard. When we’re back from America I’ll call you.’ I’m still waiting for that call…

He spent two seasons with Scuderia Italia in F1, his last at racing’s highest tier

Motorsport Images

“Meanwhile my good friend from karting and F3, Roberto Ravaglia, who was now in touring cars with BMW, suggested my name to them. I’d never thought of myself as a touring car driver, but I always want to try new things, so I did a 500km race in a 635 at Monza. Then they offered me a works ride for 1986, to fit in with my F3000 commitments.

It was a good manufacturer, and it was a salary. And I kept the F3000 going and finished second in the series that year.

“But I certainly hadn’t given up on F1. For 1987 I got a very good offer from Tyrrell.

I have never had a manager, and I have never been a very good manager of myself. Tyrrell wanted me to bring $200,000, and a friend offered to lend it to me because he said he knew I’d pay it back. But it didn’t feel right, I don’t like to owe money, and I didn’t do it. Then Ron Dennis called me. McLaren was finishing with the TAG-Porsche engine, they’d done their deal with Honda, and Senna was joining Prost to drive the MP4/4 in 1988. Ron wanted me to work with Honda in Japan on the engine development. I’d be testing three days every other week at Suzuka, and when not working with Honda I could race what I liked in Japan.

“So I moved to Japan. It was a very big operation, testing with engineers from Honda and from McLaren, including Tim Wright and Neil Trundle. Meanwhile I got a drive in Japanese F3000, which was very competitive, and then in Grand Champion cars, which are like the centre-seat Can-Am cars. So I was busy.

“Ron Dennis was very straight with me: he said with Senna and Prost in the team it was unlikely I’d ever get a race, but working alongside those two I would learn a lot. And both of them treated me like part of the team.

I remember once when we were testing at Jerez, I did the first two days, Alain did the next two, and he said, ‘You were driving very well. To beat your time I had to improve the car a lot and then try hard.’ That meant a lot to me.

“Ayrton was always polite. When I brought my parents to a race, he would go over to them, shake their hands and say hello. I knew him from karting: we did two world championships together. I won’t say he was a friend. When he died, suddenly everybody was his friend, and friendship is a big word. But I knew him, he knew me. Then in F3, Euroracing wanted another driver alongside me, and I offered to introduce them to Ayrton. I nearly shot myself in the foot there! I talked to him, but he said he had decided to do F3 in England.

“At McLaren we talked about the car, and especially the engine mapping. Ayrton was very sensitive to power delivery: in those days it was a mechanical throttle, not fly-by-wire, and there was a lot of work to do. In 1990, the year Senna’s McLaren crashed into Prost’s Ferrari at Suzuka, Honda had developed a hotter engine for Senna. By then I was doing F1 for Scuderia Italia, but I was still testing for McLaren. Before Japan, Honda wanted me to do a full race distance at Estoril to see if the new engine would last the distance.

Pirro won two ALMS titles with Audi, in 2001 and here in 2005

Motorsport Images

“They said, ‘But you have to drive like Senna.’ They showed me his traces. The engine would blow up at 13,500rpm, and on the graph every single one of his downshifts was taking the revs to precisely between 13,200 and 13,400. When you are down-shifting in F1 it is so quick, to time it right so that the wheels drive the engine up to that figure, no more, no less, is incredibly difficult. I said to the Honda guys, ‘Give me something that is humanly possible!’ That gives you an idea of the level Senna worked at, his attention to detail.

“During 1988 Ferrari offered me a contract, but it was for testing, with only an option for them to give me any racing. I told them it was no better than what I had with McLaren, and as Ron had been good to me I felt a loyalty to him. So I said ‘No’ to Ferrari, and I don’t think they liked that. In 1989 Larrousse came after me with an F1 contract. I tested the car, and I would have signed, but Ron said, ‘Hang on. Don’t say yes yet.’ Flavio Briatore had come into Benetton, and Ron guessed there could be something for me there.

“Flavio wanted to take control and exert his authority. He fired some people – including Johnny Herbert – and he signed me. It was a golden opportunity. But I didn’t get the results. No excuses, but maybe two reasons. One was I was too tall for the car, which was designed around Alessandro Nannini and Johnny Herbert. My head stuck out of the cockpit, and at Hockenheim, when I was lying third, my head was shaking around so much I hit a kerb. In Jerez, when I was fourth, my legs were so crammed in, it trapped a nerve and they started to go numb. I lost sensitivity in my right leg and could not feel the accelerator or the brake any more, and I went off. That’s just how it was.

“Also I should have been more fit. I was travelling so much: F1 for Benetton, testing for McLaren, still doing Grand Champion in Japan, and BMW too – I won the Nürburgring 24 Hours, and the Wellington 500 in New Zealand [which he won for BMW four years running]. In 1989 I got on an aeroplane 109 times: that’s once every 3.3 days.

Formation finish in 2000 as Pirro celebrates Audi’s Le Mans win

Motorsport Images

“At the end of 1989 Flavio didn’t bother to tell me I was fired, but I read in a magazine that they’d signed Nelson Piquet and were keeping Nannini. That’s F1. But Marlboro helped me to get a seat in Scuderia Italia, where my team-mate was my friend Andrea de Cesaris. The car was built by Dallara and, to be diplomatic, it was conservative. [Neither of them scored any points all season, although Emanuele qualified ninth at Monaco, only for the car to fail on the parade lap.] For 1991 JJ Lehto was my team-mate. Nigel Couperthwaite designed a good car and we had Judd engines. I was sixth at Monaco and seventh at Spa, I qualified seventh in Hungary, there were a few other reasonable races. But we had to pre-qualify, which was a nightmare.

“After that F1 was finished for me, but I’d kept a foot in the touring car camp and I had a good deal with BMW. We did the DTM, which was a heavy series, Mercedes versus BMW. I had some good drives, I won some races – and I won Macau twice. Mercedes came after me, offered me a lot of money to switch, but I decided to stay with BMW. But in the end the politics at BMW forced me to move. They’d promised I would stay with the Schnitzer team, where I was happy, but they moved me to Bigazzi. At the end of 1993 we agreed to part.

“Now I had nowhere to go, but Schnitzer’s Charley Lamm kindly told me that a major manufacturer was coming back into racing, and gave me the phone number of a man I had never heard of, a Doktor Ullrich. And that was how my 15-year racing career with Audi began.

On top of the Le Mans podium for a fifth time, with Frank Biela and Marco Werner in 2007

Motorsport Images

“To start with it was just touring cars, and that was a wonderful period. I won two Italian championships, and then I won the German championship. At Audi you felt part of the family, you were able to interact with the top people there. I was very happy, but I soon felt the need for something faster, more critical.

“Then at the end of 1997 I was summoned to Ingolstadt to be told, in absolute confidence: ‘We are preparing a sports car for Le Mans.’ I was amazed, and delighted. It was exactly what I needed, and I was part of Audi’s Le Mans effort from day one. There is nowhere in the world where you can simulate Le Mans in testing: the only way to prepare for the race is to do the race. And you can’t afford to have a failure. To learn the lessons you have to get to the end. In that first race in 1999 we did get to the end, in third and fourth places, which was beyond our expectations.

“We’d learned a lot, and out of this experience Audi produced the R8, surely one of the best sports cars ever built. It was very strong, and the philosophy was: you can’t guarantee you’ll build a car that will never break, so let’s build a car on which, if anything does break, it can be changed very, very quickly. As long as the car makes it back to the pits – even if you come back on three wheels with a badly damaged car – you can change anything except the engine and the tub. At Le Mans the transmission is probably the weakest element, so the R8 had a detachable rear end and everything could be changed, fast.

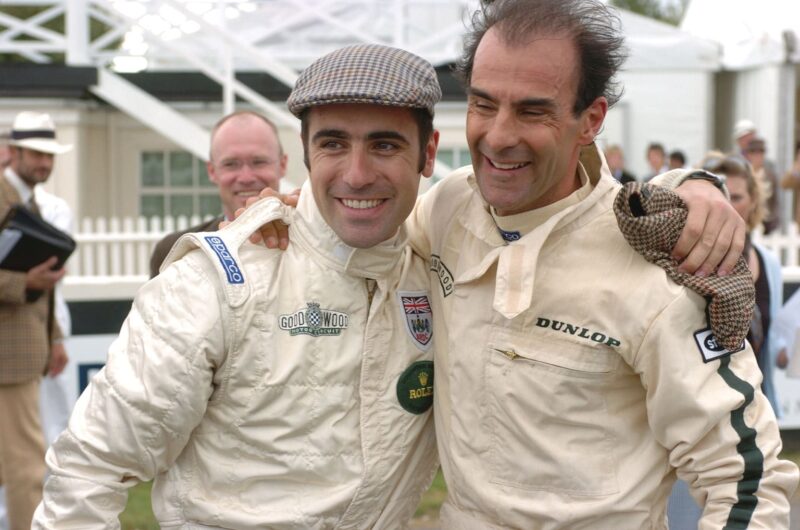

Relishing the 2005 Goodwood Revival with Dario Franchitti

Motorsport Images

“The mechanics practised endlessly, changing every part of the car. And the year of our first victory, 2000, late in the race we had a slight concern about a rear wheel bearing. Because we had a decent lead we decided to come in and change the entire rear end. The car was wheeled into the garage, and the other teams assumed we were out of the race. In about six minutes the car was back on the track, and we won.

“The second year, 2001, was probably the hardest. Michele had died two months earlier, which hit all of us really hard. The team considered withdrawing out of respect, but then it was decided that we should try to win again in his honour. But we went with sorrow, and maybe a little more fear than usual. I had a tyre blow out in practice, which made me more nervous. And the race was very difficult. It rained for a lot of the distance, and at night in heavy rain Le Mans is scary. I was more happy that the race was over than that we’d won it.

“Then in 2002 we made it three wins in a row. I was with the same co-drivers each time, Tom Kristensen and Frank Biela. Out of the car our characters are very different: Frank is a quiet person, I tend to laugh and joke, Tom is very professional and cool. The key to your relationship with your co-drivers is the trust between you, and it takes time to build that trust, through testing, through racing. Frank and I had been the leading drivers in the touring car team, so we had a lot of respect for each other. Tom is now the most winning Le Mans driver of all time, but when he was the new boy there was maybe a question mark about him: he was a bit over-exuberant, wanting to prove himself. But soon he became a very wise endurance driver, which is just what you want.

Final Audi Le Mans outing in 2008

Motorsport Images

“There was a very strong DNA at Audi. It treated all its drivers equally, there was no one who was a big star. Of course there was rivalry, but it was an honest rivalry: to all of us, the team was what mattered. When you are part of a good team you automatically deliver because that is how it works, that is the air you breathe.

“To win Le Mans every single thing has to work. You have to have the moon, Jupiter, Saturn, Pluto, all in a line. There is not so much you can do to win it, but there is a lot you can do to throw it away. With today’s electronics and telemetry you no longer have to worry about driving to preserve the car, and listening out for the smallest problem. With paddle shifting you can’t miss a shift and break the engine. So to be competitive you are required to drive on the limit every single lap, which is really good for a driver. But all the time you have to be immaculately tidy: you mustn’t do anything silly, like touching a kerb.”

In 2006 came Audi’s switch to diesel with the R10 TDI. “That was a very big change, technically. Now it’s accepted that you can make a very good diesel race engine, but then it looked really peculiar. When they told me, again in great secrecy, what they were planning, I would have worried if it hadn’t come from a team like Audi.

“I was the first to drive the car in a test at Vallelunga. By then the R8 was six years old, and the R10 was a huge leap forward in everything: aerodynamics, car dynamics, electronics. It was like a spacecraft. And the engine was so smooth, so quiet, that at first I found it hard to drive, because in a racing car you drive on the sound. The engine was extremely powerful, but also extremely heavy, and the car was bulky. It could have been a wild beast, but in fact it was extremely nice to drive.

A third Le Mans win in 2002

Motorsport Images

“I scored the first diesel Le Mans win, which pleased me. Now I was with Frank and Marco Werner, and the three of us won again in 2007.

“In 2008 I knew it was my last Le Mans, and I really wanted to get a 10th consecutive podium. But we had some problems with set-up, ending up with a car that was too slow and not nice to drive. It wasn’t a good farewell to the race that had meant so much to me.

“For most of my time at Audi I was also doing the American Le Mans Series, which I loved. Most of the classic European circuits now have a mirror-smooth surface and gentler kerbs, and have been modified in other ways because of modern F1 requirements. The American circuits are like going back in time: rougher surfaces with patches, high kerbs that you cannot touch, more challenging altogether. If you make a mistake you pay for it, and I like that. Also the paddocks are open, the spectators can get close to the drivers, the atmosphere is really nice. The organisers are very professional: they enforce the rules, but still they manage to be your friends.”

Emanuele was ALMS Champion twice, in 2001 and 2005, and his last race for Audi was the final 2008 event at Laguna Seca. “The ALMS rounds were two-driver races, roughly an hour and 20 minutes each, and it’s the second stint that really counts. Dr Ullrich used the ALMS to try out different younger co-drivers with the experienced guys. That day I was with Christijan Albers, and when I took over the car at half-distance we were eighth.

I was determined to go out with a win, and I managed to get through into a good lead. My idea of how to win a race used to be to get in front from the start and stay there, but in ALMS you developed your overtaking skills. You had to attack a lot, especially on their tighter circuits.

“Then there was a safety car period, and Marco Werner was sitting behind me. Trundling slowly around I lost concentration, and when the safety car pulled off I had second gear instead of first. Marco, surprised, went past and won the race. I’d made a stupid mistake, and I finished second. That’s life, and you can’t change it. But a nice detail was that Marco was wearing a visor strip for that race that said: ‘EP Thanks For The Memories.’”

Emanuele didn’t retire completely at that point, for Paul Drayson tempted him into his Lola-Judd for Le Mans in 2010, and he also had an Australian Supercar ride in 2011. Now – apart from the hotel he owns in the Italian Alps, and other business ventures – his time is fully taken up with his work around the world for the FIA, for the Italian Federation, and as an ambassador for Audi. “I am a steward at some Grands Prix and a member of the Drivers’ Commission, in Italy I am a member of the circuit and safety commission, and I am president of the Karting Federation. Then I am vice-president of the GPDC, which is what the Anciens Pilotes is now called, and also of the Le Mans Drivers’ Club. Because racing has been my life, I want to give something back. None of these things I went looking for. I was asked to do them, and I am very bad at saying ‘No’.”

And there’s something else that Emanuele throws himself into with wholehearted enthusiasm: historic racing. “There are two sorts of historic racers: the ones who aren’t interested in the past – sometimes younger guys racing for rich owners – and the ones who are. The history of our sport always meant a lot to me. As a young boy I read that Tazio Nuvolari always raced with a phrase stitched on his overalls, with a cross and a heart, so I had the same phrase painted on my helmet throughout my racing career: Fosti con me nel pericolo e nella vittoria. It means: You will be with me in danger and in victory.

“The Goodwood Revival is a perfect mix: the location, the history, the knowledgeable public, even the cricket match! It is a privilege to see some of the old drivers in their original cars, like Stirling Moss or Richard Attwood. The circuit looks simple, but in fact it’s quite difficult, it’s a track that can bite you. For Shaun Lynn I have raced his Cobra and the original lightweight E-type, 4 WPD. That is my favourite historic car. It’s not as quick as the Cobras, but it really has such great presence.

“Racing a modern car is all about the stopwatch. If the stopwatch is good, you are good. Racing a valuable historic car is different: treat it with respect, leave a margin, don’t be lured by the occasion into overdoing things. The satisfaction should come not from winning, but from driving the car as it should be driven, getting your lines absolutely right, balancing a slide, making perfect downshifts.

“The spirit of historic racing is now in danger: more and more competitive, driving standards changing, cars straying from the correct specification. With a big enough wallet you can develop the cars far ahead of where they were in period, and a lot of this is difficult to police. For some people winning has become too important, and they could spoil it for everybody else. I have been a hard competitor all my life, I have only driven to win. But because of the value and importance of the cars, historic racing should be different.”

Emanuele’s strong views spring from his true love of motor sport. Whether it’s historic racing, being an F1 steward, sitting on various FIA and Italian commissions, representing Audi at endurance races around the world, meeting with the Anciens Pilotes, or assembling in minute detail the models in his basement: his passion for motor racing remains undimmed. That shooting star a little boy saw over Rome, one night more than 40 years ago, has delivered its promise.