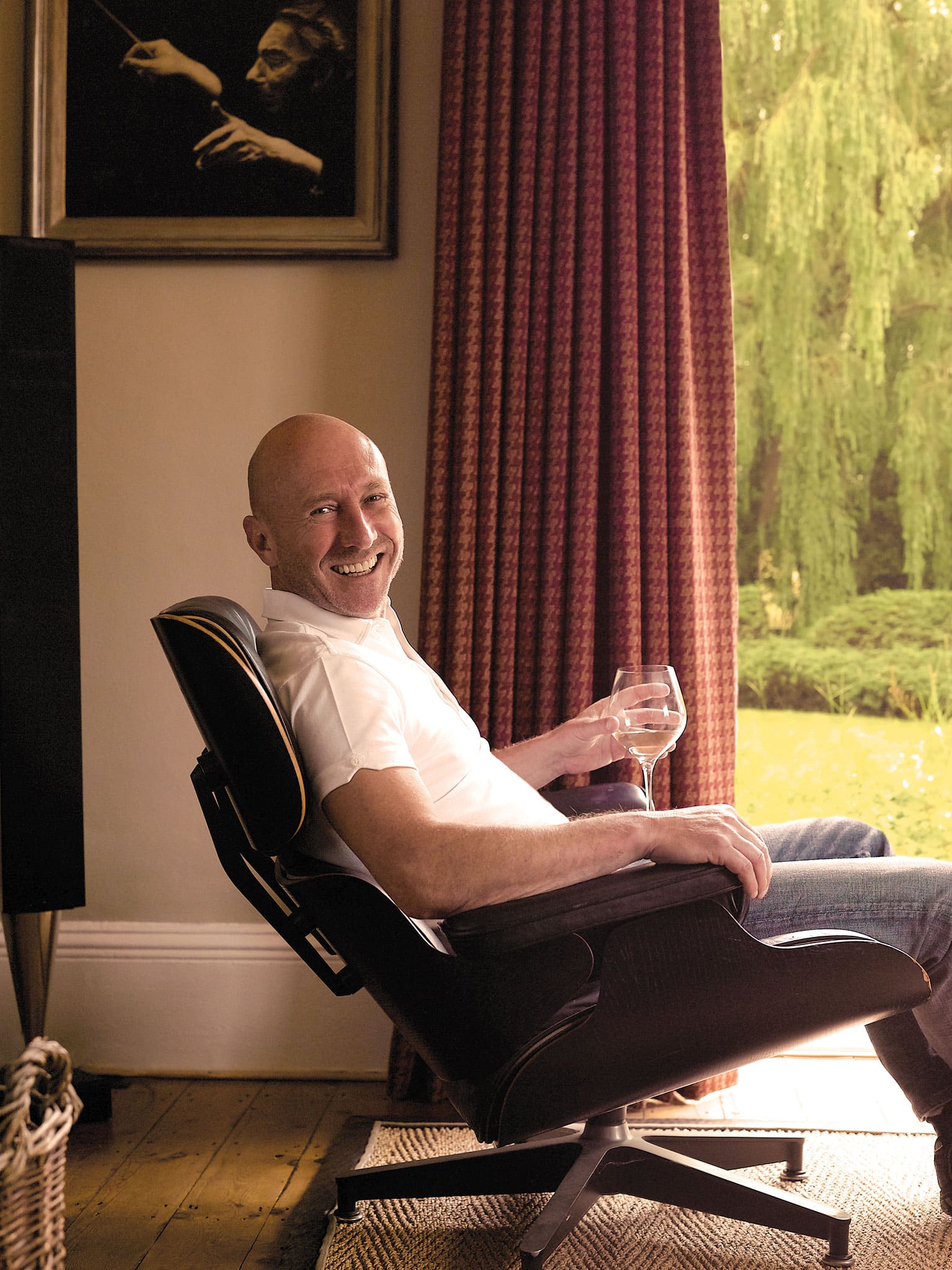

Lunch with... Perry McCarthy

Formula Ford champion, F3 front-runner, Grand Prix non-qualifier, pioneering Stig, works Audi driver and perennial optimist...

James Mitchell

The road to Formula 1 is steep and stony. For every rookie who takes his place on a Grand Prix grid there’s a long queue of hopefuls who never get there. Among the ones who come closest, talent – pure talent – may not be the deciding factor. Contacts, luck and above all money will probably play a larger part.

Of those who do make it into F1, some go onto greatness, to podiums, to victories, even to championship titles. As for the others, they may have plenty of ability, but perhaps they’re never in the right team, never get the breaks, are never quite in the right place at the right time. They may score the odd championship point, but after a season or two they move on. They may subsequently enjoy a lucrative career in sports car racing or in a well-funded series like DTM; but in F1 terms they are consigned to the anoraks’ lists of forgotten also-rans.

And then there’s Perry McCarthy. Rather than merely being buried in the history books he is still, 22 years after his fleeting involvement with the top level of motor sport, remembered as maybe the most unsuccessful Formula 1 driver of all time. It’s not a title one would wish on one’s worst enemy, but in an ironic way he is almost proud of it. “There’s success. And, unfortunately, there’s failure. What I can’t accept is mediocrity.”

Even though it did end in failure, the story of Perry McCarthy’s unsinkable determination to get to F1, his single-mindedness, his passion, his unshakeable self-belief, is exhilarating. He just knew, with every fibre of his being, that he had what it took to make it in F1, even though he had no money to do it and no contacts to help him. So he worked on North Sea oil rigs to build up enough funds to get himself through the lower formulae, and then he risked everything, running up debts (at 1990s values) of over £300,000 and even losing his house, to realise his dream.

He did get there, to the extent of having a seat in an amateurish, underfunded team for just eight Grands Prix, until the team owner was arrested in the paddock on fraud charges and the whole outfit disappeared overnight. But he didn’t start a single race. At one his licence was deemed inadequate. At another the team failed to turn up. At another the cars had no engines because of an unpaid freight bill. He failed to qualify for the other five, and invariably the car only lasted a few laps. At one Grand Prix it managed to travel on all of 20 metres of track, so he barely got out of the pitlane.

Today Perry recounts the story of his extraordinary journey with downbeat realism and unquenchable humour. Having emerged from his ruined career with nothing except huge debts, he has worked ceaselessly to rebuild a life for himself and his family. His long-suffering wife Karen has stood by him unwaveringly for 30 years, even when, with two small babies, she lost the roof over her head. Now they live in a delightful Queen Anne farmhouse where Karen serves an excellent lunch. Their three daughters have inherited their father’s determination and are making their way respectively as an artist, a City trader and an actress.

After winning a junior FF1600 title in 1983, Perry stepped up to senior Formula Ford, but early-season Oulton Park spill soon sidelined him

Motorsport Images

Much of Perry’s income comes from making speeches and presentations to business audiences around the world: one wonders what a group of Japanese bankers makes of his Essex humour, but his lessons about life, learned the hard way, are inspirational. He has worked in TV – he was the original Stig on Top Gear – and he has made some shrewd investments. “Some have done well, a couple haven’t. But by and large it’s all added up. You have to be brave and go for what you believe in. You can’t eradicate risk, you still have to take chances. But that’s riding the ride and having the adventure – just like racing.”

He was launched off car 20, driven by Marussia F1 boss John Booth

Motorsport Images

Perry was born in a council flat in Stepney, but when he was five the family moved out into Essex. “Dad was ‘on the brush’, meaning he was a painter and decorator. He was the classic East End boy: down the pub, telling jokes, getting the next round in.

There’s a lot of him in me. I went to the toughest comprehensive in the area, and I was small for my age, but I would never back out of an argument. If anybody tried bullying me, they only did it once. I found school very frustrating, because it all seemed to be going too slowly. I was good at picking up stuff, and I got bored quickly.

“Motor racing just wasn’t on my radar, although I used to get up to stunts on my push-bike that you wouldn’t believe. When I was 17 I scraped together £100 which got me an old Ford Escort with galloping rot, and immediately I became a complete nightmare on the roads. I got a bit of a reputation for this, and I had a number of conversations with the local police. I had no idea what I wanted to do, except I wanted it to be more difficult and more exciting than what I was doing as a shipping clerk. I also had a part-time job in a friend’s music shop and, perhaps because he thought it would divert my hooliganism in a safer direction, he introduced me to a friend, Les Ager, who was an instructor at the Brands Hatch Racing School.

“I went along for an afternoon and drove a school Talbot Sunbeam around as fast as I could, over-driving it dreadfully, nearly putting it in the barriers a couple of times. I couldn’t understand why Les was sitting impassively in the passenger seat, totally unimpressed. Then he took me round and, as well as being terrified, I saw how smooth he was, and that I’d been doing it all wrong. I had another go, and this time it flowed, and I was ahead of the car rather than trying to keep up with it. At last I had found something I wanted to do. I’d never been to a motor race, but I left Brands Hatch that afternoon knowing I was going to be a racing driver.”

He was a British F3 frontrunner in 1986-87

Motorsport Images

But that needed money, and Perry had none. So, showing typical determination, he went to work on North Sea oil rigs, where his father was now running a paint stripping and anti-corrosion business. “I did two years on the rigs, 12 to 16 hours a day hanging suspended 130 feet up over the crashing waves, sand-blasting and coating. We’d stay there for three weeks at a time, sleeping on the rigs. During my time ashore I talked to everybody I met, in pubs, on the train, in check-out queues, asking for sponsorship, or asking for contacts who might help me to find sponsorship. And in the end I did get a few local firms who liked my patter enough to chip in a bit, which I added to the oil rig money.

“From reading the magazines I knew Formula Ford was the place to start, so I went and watched some FF races. I noticed a chap called Ayrton Senna da Silva who seemed to be quite useful, and his chassis was a Van Diemen, so I found out that Van Diemen was run by one Ralph Firman and I called him up. Ralph put me in touch with a team that ran his chassis, Jubilee Racing, and I bought my way into a couple of races with them at the end of the 1981 season. The first was the Champion of Brands meeting. I qualified on pole for my heat and won it, and in the final I crashed. The second was the FF World Cup, and I crashed again. But I made sure I got plenty of publicity in the local Essex papers. I told the Basildon paper I lived in Basildon, I told the Chelmsford paper I was a Chelmsford boy, and I did the same with Southend, Brentwood, Billericay and even Colchester.”

Perry continued in FF, and for 1983 he vowed that he would win the Star of Tomorrow series, or give up racing. He won six out of 10 rounds and clinched the series in the final round. A number of small deals helped him to stay in Formula Ford, just: a hotel room here, a magazine column there. He was always fast, but he crashed with monotonous regularity, and the next step to F3 seemed ever further away.

Desperation drove him to new efforts in sponsorship hunting. He rang up a leading computer company saying he was James Hunt. Perry is an excellent mimic, and the 1976 world champion’s hoarse public-school tones were well-known from his TV commentaries.

“I want to introduce you to a brilliant young rising star who can take your company’s name all the way to Formula 1. I’ll bring him to your offices so you can meet him.” Perry then turned up on the appointed day at the office of the managing director, saying that James sent his regrets but he was unwell and could not make the meeting. The MD saw through him at once, saying, “Nice try, son. There’s the door.”

In 1990-91 McCarthy shone in an IMSA Spice in the USA

Motorsport Images

After literally hundreds of approaches and hundreds of refusals, the 1986 F3 season was about to start when Perry’s sell to Essex engineering firm Hawtal Whiting bore fruit.

It came up with enough budget for him to go to Robert Synge’s Madgwick Motorsport and run as Andy Wallace’s team-mate in a works F3 Reynard. In two seasons in F3 he was always among the fastest, especially in the rain. He took a superb second place at Spa – on slicks on a damp track – and was leading the May Silverstone until, with a slipping clutch, he was pipped by Johnny Herbert. But a couple of big accidents, a persistent leg injury, various engine maladies and other mechanical problems meant that, overall, his results were disappointing.

“I owe a big debt to the lads writing the reports in the weekly magazines, because they kept my name to the fore and boosted my confidence so much, saying they thought I was really fast, really talented, and would go places. When things are tough you live on a compliment, you hug it to yourself and it keeps you going. I screwed up lots of times, obviously, but I did also have some very bad luck. I was also capable of making mistakes away from the track, wasting time with characters I thought might turn into sponsors, rushing to London to have a drink with the wrong people. Looking back I’d have done better if all that energy had just gone into my racing. But what kept Karen and me going was that she knew I wasn’t going to back off. People said to her, why do you stay with that waste of space? But she believed, like me, that either I was going to end up six foot under, or I was going to get to Formula 1.

“You must remember, it was an extraordinary time in F3. These days we’re lucky if one driver a year rises up out of F3 and gets to F1. When I was in F3 I was racing against, and sometimes beating, Damon Hill, Johnny Herbert, Mark Blundell, Julian Bailey and Martin Donnelly – all future F1 racers, and one future World Champion. One of the journalists called the six of us the Rat Pack, and it stuck. We gave each other nicknames: Damon was Secret Squirrel, because he played his cards close to his chest. John Herbert – I never call him Johnny – was Little ’Un, for obvious reasons. Markey was Mega, because he liked mega cars, mega watches, mega stuff. Julian was Grumpy, because he could be. Martin was Yer Man, because he had this Oirish way of preceding everybody’s name with ‘Yer Man’. I was Mad Dog, after a character in the Catchpole cartoon strip in Autosport who used to appear carrying the crashed remains of his car under his arm. We had so much fun together, and we are all still good mates today.”

Struggling to coax the Andrea Moda beyond the pit exit in Barcelona in 1992

Motorsport Images

The next step had to be Formula 3000, but with its much bigger costs it seemed unattainable. The stock market crash that October, Black Monday, spelt the end of Hawtal Whiting’s involvement, so Perry took to hanging around in the London Hilton nursing a single cup of coffee and striking up conversations with rich and important-looking strangers in case he could persuade one to sponsor a future Formula 1 driver. For the first eight months of 1988 he didn’t get in a racing car. Come August, when the carnage of that infamous Brands Hatch meeting left Little ’Un with badly smashed legs, another of the injured was Gregor Foitek, who had started the chain reaction by colliding with Herbert. Perry found himself summoned to the Birmingham Superprix on the following weekend to drive the spare Lola vacated by the injured Foitek, if he could find £8000 in four days. Being Perry, he found it somehow. In the first of two qualifying sessions the diff broke. In the second it rained: even so Perry, on the limit, was impressively quick in the wet – until he crashed.

Meanwhile Ron Tauranac was having a difficult F3000 season, with his Ralt cars frequently failing to qualify. He needed another driver, and Perry ramped up his debts to £215,000 to join the team for the three remaining races of the season. Two ended in accidents that weren’t his fault; the third, struggling with handling problems, produced a brave but almost unnoticed 16th and last place.

The next season he scraped together the funds for three races in Roger Cowman’s Lola. Birmingham was a DNQ again, courtesy of a misfire in the first session and, in the second, an errant mechanic who stepped in front of his car as he was accelerating down the pitlane. Spa was much better. While it was wet Perry was one of the quickest in qualifying, but when it dried he slipped to 11th. A bad start made that 16th, but he carved through the field and just missed getting a point for sixth. That time he did get noticed.

“To save travel expenses I hitched a ride to the next round, at Le Mans – and my ride broke down, so I had to get FIA dispensation to sign on a day late. Then I missed first practice because the hydraulic lift on Roger’s transporter jammed with the Lola still up in the air, and we had to borrow a crane to get it down. In the second session I had a misfire and a dodgy gearbox, so I got in one flying lap, on cold tyres. I scraped into the race 26th and last qualifier. But in the morning warm-up I was third quickest, faster than Jean Alesi, who was leading the championship. On the first lap I went from 26th to 16th, and then I got thumped by Marco Greco. I pressed on, without a clutch now, and as my engine started to tighten up I brought it home 15th, just ahead of Damon Hill.” That was Perry’s last F3000 race, and Formula 1 was no nearer.

For the next two seasons Perry’s racing was in the USA, after Roger Cowman put in a good word with Julian Randles, who was running the Spice sports car effort in IMSA. In his first outing, at Mid-Ohio, Perry won the IMSA Lights class, and then he moved up to GTP among the works Silk Cut Jaguars, Nissans, Toyotas and Porsches. “We went to Watkins Glen, which was a turbo circuit, and we were fastest normally aspirated car. And at the start of the race – every dog gets lucky sometimes – it started to rain, and I came through. On lap three I took the lead from Davy Jones in the Jaguar and pulled away. But the car broke.” He earned some pole positions, led some races, and there was a strong second at Atlanta and a third at Laguna Seca, but more often than not the car was stricken with reliability problems. Nevertheless, everybody in motor racing now knew how hungry Perry was, and in March 1992 he had a phone call from Eddie Jordan’s solicitor, Fred Rodgers, who’d heard that a man called Duffy Sheerdown was representing a new team in Formula 1 and wanted to talk to him.

A rare shot of the 92 Andrea Moda in action. Roberto Moreno managed to qualify the car once, but Perry had no such luck

Motorsport Images

“I was pretty desperate by now. All the drives in America had dried up, I was £300,000 in debt, and we had no money to buy our cornflakes for breakfast. I could probably have earned a decent living in sports car racing, but Formula 1 was my only goal. So I went to see this guy Duffy. Turned out that a young Italian with a fashion company, Andrea Sassetti, had decided he wanted to be an F1 boss and had bought up the Coloni team. He’d signed Alex Caffi and Enrico Bertaggia as drivers, but he missed the first F1 race of the season because he hadn’t paid the $100,000 deposit required by the rules. Then he chucked the Colonis and got Nick Wirth at Simtek to build up cars to a design Nick had done earlier for an aborted BMW project. When the cars arrived at round two, in Mexico, they were still in bits, and they never ran.

“Caffi and Bertaggia moaned to the press about all this, so Sassetti fired them – and now he needed two more drivers. Somehow he convinced Roberto Moreno to join him, I don’t know how: a few months before Roberto had finished fourth in the Belgian Grand Prix for Benetton. Meanwhile Duffy and Mike Francis, who’d been Nigel Mansell’s manager at one point, lobbied hard for me to get the other seat. So Andrea said ‘Si’, and I was an F1 driver.

“Mind you, I wasn’t being paid. I wasn’t even getting my expenses to get to the races. So I went to Chequers Travel, who ran package tours to races, and got them to employ me as a courier in return for my air ticket to and from the races. I never thought ‘I’m a Formula 1 driver, I shouldn’t be doing this, this is beneath me’. It had become normal for me to do whatever it took to get in the car. I wanted everyone to see that, even if the car was slower than anything else out there, Perry McCarthy was getting more out of it than anybody else possibly could.

“To race in Formula 1 FISA has to grant you a Superlicence, which is based on what you have done in the lesser formulae. After my stop-start career FISA weren’t sure I should have one, but the MSA here in the UK lobbied hard on my behalf, and eventually FISA relented and I was on my way to Brazil. In the Interlagos paddock a FISA representative handed over the cherished licence. But a few hours later race director Roland Bruynseraede demanded I return the licence, saying there had been a mistake and I was not entitled to it.

“I was devastated, of course. When I’d picked myself off the floor I went storming off to see Bernie. Bernie told me Bruynseraede was right, because I hadn’t done a full year in F3000. Well, I really lost it then. I was thumping the table, shouting at Bernie. I told him how Karen and I had struggled, how we’d lost the house, but most of all how I’d beaten 11 of the drivers currently on the F1 grid.

Perry as a central cog to the Audi Sport crew in 1999

Motorsport Images

“Well, Bernie likes a fighter. First he called in the Brazilian member of the F1 Commission, who was clearly terrified of him, and got him on side. Then he told me it would be discussed at the next meeting of the Commission, and that he and Max Mosley would vote for me. He told me to lobby Frank Williams, Ron Dennis, Flavio Briatore, Marco Piccinini at Ferrari and Giancarlo Minardi. Frank, Ron and Giancarlo were really nice to me, but Flav looked at me like I was a bug on the clean windscreen of his car, and I don’t think he had a clue who I was. However, he did vote for me in the end.

“Meanwhile the British press went ballistic in my support – one journo pointed out that under the current rules Gilles Villeneuve would have been refused a licence – and after the Commission meeting Max called me at home and said I had my licence back.”

While all this was going on Bertaggia had come up with $1 million sponsorship to get himself back in the team, so Sassetti couldn’t wait to eject Perry and take Bertaggia back. But under FISA rules he couldn’t change his drivers again, and to his fury he had to stick with Perry. This was a major factor in how unwelcome Perry was to remain at Andrea Moda, and how little effort would be put into making his car competitive.

So to the Spanish Grand Prix and pre-qualifying. Because of the size of the F1 entry in those days, six drivers had to come out for an early Friday morning knock-out session to reduce the field to the 30 cars allowed to take part in qualifying. “On Thursday night they were still building the car in the paddock garage, and at 11pm I finally got somebody to run me to the team hotel on the other side of Barcelona. I was in a six-bedded room with the mechanics, but they were all still at the track. I assumed they’d come back later, we’d all get up at 5.30am and I could go back to the track with them for pre-qualifying at 8am. I woke with a jerk at 7.25am. They hadn’t come back at all. I’d spent 10 years trying to get to this point, and now I was going to be late for my F1 debut. I threw on some clothes, found Andrea Sassetti’s brother in hotel reception just coming in the worse for wear after a night on the tiles, and persuaded him to drive me to the circuit, and quick. He was doing 90mph through the city streets in his poor little rental car, through red lights, down one-way streets the wrong way. It was all insane and I was terrified. But by 8.05am I was in the pits garage, in my race gear, in the car – and they couldn’t start it. Too much Quik-Start down the inlet trumpets and a sheet of flame shot up, burning the new Gilles Villeneuve colours off my crash helmet. They threw a blanket over me, put the fire out and got the engine started. I drove down the pit lane and over the white line onto the circuit – and the engine spluttered and stopped. Because I was officially on the track they couldn’t pull me back and get me started again. After 20 yards, my F1 debut was over.”

Perry failed to pre-qualify at Imola, too, because of a binding differential; and the next race was Monaco. “I was standing in Gatwick Airport wearing my Chequers Travel badge and handing out tickets. One lady asked why I was going to Monaco, and I said I was one of the Grand Prix drivers. Her eyes lit up: ‘Do you all do this?’ ‘Of course, madam,’ I replied. ‘Nigel Mansell’s just over there with Page & Moy!’

“I did three laps of pre-qualifying, and the pounding I got around Monaco was pretty desperate, giving me double vision, because the team still hadn’t made a proper seat for me.”

Perry got himself to Canada by getting a company to pay him to make a speech to his clients: but he had no car to drive. The team turned up but there were no engines, which had been withheld against unpaid debts. For the French Grand Prix there were no cars at all because the transporter hadn’t got through the national lorry drivers’ strike, although the other teams managed it.

So to Silverstone where, as one of five British drivers with Mansell, Brundle, Hill and Herbert, Perry was getting a lot of limelight. But still he didn’t get through pre-qualifying. He was sent out onto a dry track on worn rain tyres, and on the second lap the clutch exploded. “To let all the fans down at Silverstone really hurt. Here was this bundle of energy and passion and hopefully some talent, ready to do whatever it took in front of his home crowd, and it just made me look silly. But I would never let anybody see that.” Typically inventive, he had some T-shirts made up saying on the front, “Let Pel Out!” and on the back, “Car 35…where are you?” He and his friends sold more than 1000 to the Silverstone crowd, which raised some badly needed funds for him and Karen.

After the Silverstone debacle Perry decided to have things out with Sassetti, and got himself out to Italy to confront him. This achieved nothing except to bring their mutual hostility out into the open. It was clear that Sassetti was only fielding a car for Perry to fulfil his contractual obligation to FISA to run two cars, and would much rather have got his hands on Berttagia’s sponsor’s million bucks. At pre-qualifying for the next race, Hockenheim, Perry managed just one lap with a misfiring engine. In Hungary he sat in the pitlane fuming while the team worked on Moreno’s car. He was only let out 45 seconds before the flag came out to end the session, and couldn’t even get in a flying lap.

This time Perry really saw red. He tore into Sassetti and his team, saying they were making no effort to give him the equipment he needed to have a proper go at qualifying. Perry’s timing in this was unfortunate: Footwork boss Jackie Oliver had noticed Perry’s determination and decided to offer him a test, but wanting to do things by the book he first asked Sassetti’s permission to approach his contracted driver. Sassetti, his ears still ringing from Perry’s invective, was delighted to be offered an opportunity to damage Perry’s career further, and refused permission.

So to Spa, where a smaller field meant no pre-qualifying. But in qualifying proper, as Perry was trying to get into the race, his steering stiffened up and he went off the road. He later found that his rack had been switched over from Moreno’s car after Roberto had complained that it was going stiff under downforce.

And that was the end. Suddenly the Andrea Moda pit was full of Belgian police, arresting Sassetti on allegations of fraud. FISA later banned the team for bringing the sport into disrepute, and Perry McCarthy’s Formula 1 career was over – without him completing a single racing lap.

“Let’s not beat about the bush. Whatever the reasons, I was the mutt of the pitlane in 1992. But I do wonder if I’d have generated the same affection, if you like, if I’d got onto the back few rows of the grid and been continually running around in 17th place. If I’d been with a slightly less shit team I might have become mediocre; but, as I say, I think mediocrity is the worst of all worlds.

“For 1993 there was the possibility of a BTCC drive with Vic Lee. That was another bad choice, because a few weeks later he was arrested on drugs offences. What followed wasn’t a good time in my life, ducking and diving, doing a sales job for a telecoms company, trading office furniture, anything to pay that month’s bills. I’d wanted to get to the top in motor sport and now I was feeling like a piece of junk. I did no more racing until 1996, when I got a drive for Lotus in GT racing in the Esprit Turbo V8. The less said about that the better, and I fell out with them irrevocably after three races. I drove a Dodge Viper at Le Mans which lasted into Sunday morning, then I had a run for Panoz in 1997. In 1998 I drove for Dyson in the Daytona 24 Hours with Butch Leitzinger and John Paul Jr. Near the end we were leading the race by three laps ahead of the 333SP Ferraris when the engine went pop.

“I’d always had a supporter in John Wickham when he tested me for the Footwork F3000 drive that eventually went to Damon, and in 1999 he and Richard Lloyd were running the Audi Sport UK R8C coupés. They got me on board, and I did Le Mans with Andy Wallace and James Weaver. The gearbox failed on Sunday morning. Earlier I’d driven a German Audi team car with Emanuele Pirro and Frank Biela at Sebring, and we were fifth.”

In 2001 Bentley was making its big push at Le Mans, and Lloyd and Wickham, who were running the project, wanted Perry in the team. He got as far as getting his Bentley overalls before somebody high up in Bentley decided his face didn’t fit. In 2003 he found himself back with Audi at Sebring – sixth with Mika Salo and Jonny Kane – and then at Le Mans with Salo and Frank Biela. Before Perry even got in the car Biela had it in third place behind the Bentleys when he made a rare mistake, missed the pit entrance when a routine stop was due, and ran out of petrol. “It was a massive disappointment. I did a total of five laps of practice and qualifying during that week, for which Audi was kind enough to pay me an awful lot of money.” After that a severe shoulder injury while training effectively forced Perry to face up to the fact that, at the age of 43, his professional motor racing career was over.

With the TV show Top Gear being relaunched in a completely new format with Jeremy Clarkson as main presenter, producer Andy Wilman had an idea for a character who would be disguised and wouldn’t speak – which is hardly appropriate for Perry McCarthy. But when they discussed it Perry saw the possibilities for fun and immediately came on board. “It really took off, and The Stig – and the joke about his identity being a secret – became a key part of it all. Unfortunately some disaffected person in the TV production office got fired, and made some money by selling the story of my true identity to a national newspaper. We lived that down, but then there was a row after I drove a famous Jaguar C-type around the test track. It was a cherished former Le Mans winner so I decided not to give it a kicking, but somebody connected with the car claimed that I had twisted the driveshafts, burned the brakes out, done all sorts of damage, and the BBC were going to be sued. They weren’t sued, of course, because it wasn’t true. But that got into the papers, too. Meanwhile my anonymity meant I couldn’t use my identity as the Stig for any other earning opportunities. So after the second series we agreed to part. Ben Collins took over from me. He did it for about seven years, and it’s somebody else now.

“I’ve had a bunch of bizarre bad luck in my career. I’m the first to admit that some of it was self-inflicted: it would have been impossible for all that to have happened without my having some input into it. But if you sat down and computed the odds against making it as a racing driver, you’d never do anything. You just have to take decisions that in any other walk of life wouldn’t stand up, decisions based on optimism and self-belief. If you want to be a driver, if you want to be a mechanic, even if you want to be a truckie, the biggest ingredient is optimism. You have to believe that you can become the cream of the crop, you’ve got to have that self-belief.

“To forge a career in motor racing, you need to be the biggest optimist in the world.”

Perry McCarthy

Career in brief

Born: 3/3/1961, Stepney, England

1981 First steps in Formula Ford

1983 Dunlop/Autosport FF1600 champion

1984-85 Senior FF1600, but missed most of ’84 after early accident

1986-87 British F3

1988-89 Occasional FIA F3000 drives

1990-91 IMSA GTP in factory Spice

1992 F1 with Andrea Moda

1993-2004 Miscellaneous GT and sports car drives, including works Audi R8C at Le Mans in ’99