Lunch with... Lola

Lola’s founder and its saviour recall 50 years of entrepreneurial effort which has taken in almost every category of motor racing.

There are easier ways to make money than by building racing cars for sale. In fact, the major makers since the 1950s – the likes of Cooper, Lotus, Elva, Brabham, March, Reynard – have all, for one reason or another, hit the buffers and disappeared. The exception is Lola, which proudly celebrates its half-century this year. Yet it so nearly suffered the same fate.

Founder Eric Broadley, who ran the company for 40 of those 50 years, is the first to point out that it was a perilous existence. During its good times Lola was very profitable, but its fortunes hit cyclical highs and lows until, in 1997, a disastrous foray into Formula 1 propelled the company into financial crisis. It was rescued by former customer Martin Birrane, who has been Lola’s chairman ever since.

Eric has never been one for the limelight, yet he agrees to talk about his Lola life over lunch in the Old Bridge Hotel in Huntingdon, where important Lola visitors like Carl Haas used to be wined and dined. Martin joins us too. An energetic, entertaining 79-year-old, Eric looks back on Lola’s long haul with wry humour, confirming that it was very hard graft.

“As a young man I was pushed into being a quantity surveyor, which I found deadly boring. So I started managing and engineering new building projects, which was more challenging. I had no interest whatever in motor racing, but my cousin Graham was building an Austin 7 Special, and he roped me in to help put it together. One day he let me race it, at Silverstone. I was dreadfully slow, but I found myself hooked. But I was more into engineering and constructing a car than driving it, so I decided to build an 1172 Formula car.”

This first Ford 10 Special was conventional, but Eric calculated everything with great care. It was built with passionate attention to detail, it was light, and it handled superbly. Already, the Lola criteria had been set. With Eric at the wheel it was unbeaten in its class during 1957, vanquishing the Lotuses that had become the pacesetters in 1172 racing, and winning the Colin Chapman Trophy – presented by the 1172 Formula’s most famous alumnus.

For a reason which Eric has never wanted to divulge, that first car was called Lola, and the name was painted on the nose above its road registration, XKM 201. Many assumed it came from a musical on in London at the time, Damn Yankees, one of whose hit songs was Whatever Lola wants, Lola gets. Others said it cocked a snook at Hornsey: a two-syllable word beginning with L, which in alphabetical order came before Lotus. Eric denies all this. “Graham came up with the name. I wasn’t keen on it. Like a lot of things in the early days, it wasn’t planned, but I was too busy with everything else and it stuck. I think it had something to do with one of Graham’s girlfriends…”

For 1958 the cousins didn’t know whether to carry on with the 1172, or do something different. “I don’t know what was going on in my head, but we decided to build an 1100 sports car. The Lotus 11 was the most successful small sports-racer of the day, and I looked at it pretty carefully, because I knew Colin Chapman was a very clever guy. But I did some calculations and I reckoned there was more performance to be found. I realised the 11’s de Dion rear end was a limiting factor.”

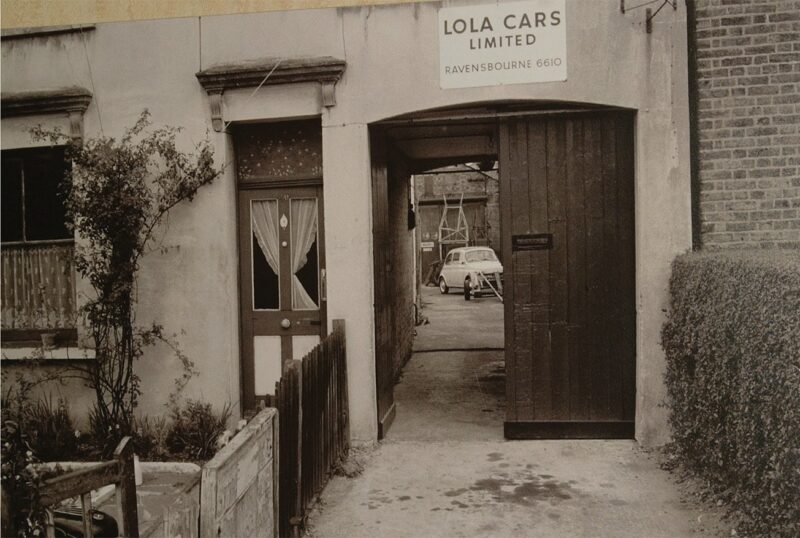

The 1172 was sold for a useful £850 (and continued winning in the hands of Alan Wershat, who changed its name to Lolita). In a lock-up behind the Broadley family clothing business in Bromley, Eric and Graham set about building a 20-gauge square-tube frame to carry all-independent suspension. The bare frame weighed just 27kgs. Many proprietary parts were used: an Austin A30 gearbox, Morris Minor front uprights and TR2 drum brakes, inboard at the rear. A single-cam Climax engine was found for £250.“We had a very tight budget, and I knew the body was going to be a problem. I phoned Maurice Gomm, the aluminium man everybody used in those days, and asked what a shell like the Lotus 11’s would cost. He came up with some astronomical figure, and I said, ‘We can’t afford it.’ Then he said, ‘I’ve got a front section and a rear section. If they’re any good to you, you can have them cheap.’ It was an order from another customer who’d gone bust on him. We had to modify it a bit, but we made it fit.”

Eric with Indy winner Graham Hill in 1966

Motorsport Images

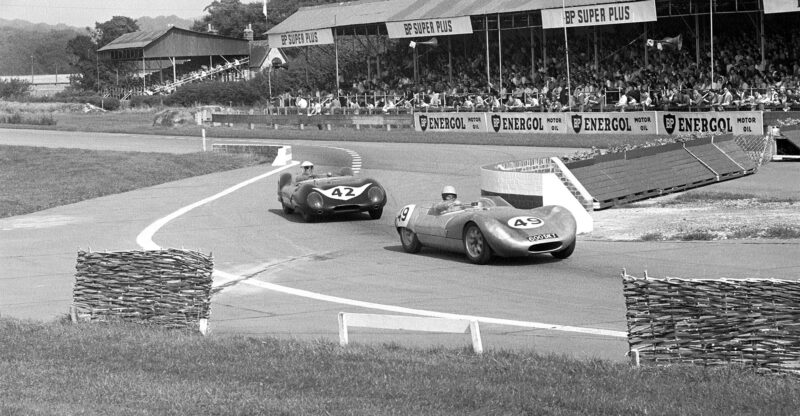

Small, neat and beautiful, the car was finished by July. Dry weight was around 370kgs. “We didn’t test it or anything, we just turned up at Crystal Palace and raced it.” In the unlimited sports car race against Lister-Jaguars and Aston DB3Ss, its lap times raised many eyebrows. Next, in a Snetterton eight-lapper, Eric wrested second place from Peter Arundell’s Lotus 11. Then came the big August Bank Holiday Brands Hatch meeting.

“I wasn’t really experienced enough to race against those guys, but in practice I went round in under a minute, which was faster than any sports car had ever been at Brands, regardless of engine size. There was a lot of interest, which made me very nervous. I won the 1100cc sports car heat pretty easily, so I was on pole for the final. But on the grid the car behind me [John Brown’s Elva] hit me up the backside. By the time I got away I was mixed up with all the traffic, and I spun at Bottom Bend. I’d overestimated the geometry effect: when I was by myself the car was very quick, but if I had to back off in a corner it was tricky.” Later, in the 1500cc sports car race, Eric started from the back of the grid and, against the likes of Graham Hill and Alan Stacey, came through to finish fourth, setting fastest lap.

“To be honest, the car’s speed was a big surprise to me, as well as everybody else. People came up and asked me if I would build one for them. But it didn’t occur to me then that it could become a business.” Then came the new car’s fourth outing, at Goodwood.

“I took my time learning the circuit, but by lap nine I’d caught up with the leaders [Mike Taylor and Keith Greene in Lotus 11s]. I wasn’t a brilliant driver, but the car was very good. I was just figuring out where might be the best place to pass them, that was how much advantage I had, when we caught a backmarker [van Vlymen’s Lotus 7] going into Madgwick. As Taylor and Greene went past him he was so unnerved that he spun. I tried to go round him, got on the grass, hit the bank and turned over.

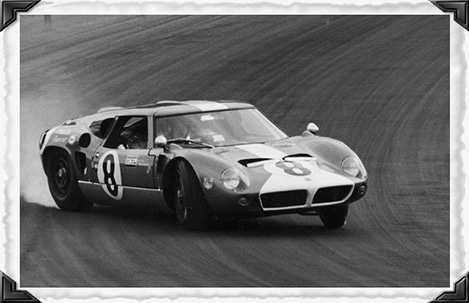

1963 Mk6 GT was Ford GT precursor

Motorsport Images

“The car was pretty badly damaged, and I was bruised and cut about the face. I limped into work on Monday morning, and my employer said, ‘I think it’s time we had a chat.’ He told me I had to make up my mind between the job and motor racing. I thought, well, we might as well have some fun. I can always get another job if it doesn’t work out.”

So Eric used his savings to set up Lola Cars Ltd, and the Lola Mark 1 went on the market. Maurice Gomm offered a corner of his shop in Byfleet to assemble the cars, and made the bodies. Not surprisingly, Colin Chapman was quick to react to the Lola’s success. “Colin panicked a bit when he saw how quick we were, and rushed out the 17 to replace the 11. I thought, oh dear, this is going to be a problem. It was a beautifully slick-looking little car. But he’d gone overboard, made one of his rare mistakes. That was a bit lucky for us, to be honest.” The 17 was even lighter than the Lola, but with its unusual strut front suspension it didn’t handle well, and the Lola remained the car to beat.

“After the first three cars were completed I went back to Bromley, and built the cars in Rob Rushbrook’s garage. I had one employee to help me. At the beginning Graham was very much involved, he was the business brain really, but he was married now, with a couple of kids, and he decided to go back and run the family clothing business. Eventually Rob Rushbrook left his own business and became works manager.”

Montoya in 2000 CART Lola

Motorsport Images

In the end around 40 Mk 1s were built. There were class wins at Sebring and in the Nürburgring 1000 Kms, while at Le Mans the Peter Ashdown/Charles Vögele Lola ran strongly for 19 hours until the engine failed. Meanwhile Eric decided to cater for the growing Formula Junior market with the 1960 Mk 2. It was probably the best front-engined Junior, with the Ford 105E engine mounted to the right of the centre-line and canted over, and the driver sitting low alongside the propshaft. But this time Chapman got it right because, just as the Lola Mk 2 was launched, so was the rear-engined Lotus 18, which became more or less invincible. Nearly 30 Mk 2s were built, but Eric dismisses it as: “all right, but not that successful. You go through a big learning curve when you do something like that, and I was no exception.”

Arear-engined Formula Junior was Eric’s inevitable response: this was the 1961 Mk 3, unusual in that it used a well-forward driving position with the fuel tank mounted centrally between engine and driver. Less than a dozen were built, and the Mk 3 rarely dented Lotus supremacy in FJ. Then, with the Mk 4, came Lola’s first effort in Formula 1.

Eric was approached by John Surtees, on behalf of the Reg Parnell-run Bowmaker F1 team, and for John and his team-mate Roy Salvadori he produced a straight-forward spaceframe car to carry the Climax V8 F1 engine. Surtees took an impressive pole position for the car’s first World Championship round, at Zandvoort, although he crashed in the race when a front wishbone broke. He went on to finish second in the British and German GPs, and took fourth place in the 1962 World Championship. Lola was also fourth in the Constructors’ Championship, ahead of Ferrari. It was an extraordinary achievement for a maiden F1 season, just four years after a hobby racer had built his spare-time sports car in a lock-up. Surtees also won the non-championship Mallory Park 2000 Guineas, beating Jim Clark, Graham Hill and Jack Brabham, and setting a new outright circuit record. But now Eric’s fertile brain was working on something completely different: a road-going supercar.

Eric and the 1172 Special that started it all

Motorsport Images

“Opportunities to expand in the racing car market seemed to be limited, so I decided to go for a road car. In the early 1960s most manufacturers weren’t into high performance cars. Before computers, it took a long time to produce a new design, and it was very difficult to produce small numbers of anything. The problem was, what to use for an engine? An American V8 seemed the way to get lots of horsepower for little money, so our supercar could be relatively cheap to produce.”

The prototype Lola Mk 6 made its bow at the Racing Car Show in January 1963, and caused a sensation. The production Ford V8 engine was bolted on the back of a strong, compact monocoque, and ex-Lotus stylist John Frayling gave the car a stubbily elegant coupé body, with minimal front and rear overhang and doors ingeniously cut into the roof to assist entry. The aim was to sell the Mk 6 as a road car, but race it first to speed up development and provide exposure. So, following the prototype, two more chassis were built, the idea being to run a pair at Le Mans that year. After an initial race at Silverstone, Tony Maggs and Bob Olthoff ran in the Nürburgring 1000 Kms but retired, and then a single car went to Le Mans for Richard Attwood and David Hobbs. It was 12th at half distance, but on Sunday morning, with Hobbs at the wheel, it jumped out of gear going into Tertre Rouge and crashed.

However, the Lola GT had done enough to attract the attention of the Ford Motor Company. Having failed to buy Ferrari, Ford was pursuing an “if you can’t join them, beat them” policy in its determination to win Le Mans, and an envoy was despatched to England to talk to the guys who’d made that sporty little coop with one of Henry’s V8s in the back.

Frank Gardner developed the F5000 T300

Motorsport Images

“When you’re a small, young company, if Ford comes to you and says, ‘Do a project for us,’ it’s something you can’t turn down. It was an opportunity for us to grow. But it was a horrendous experience, horrendous. It was probably typical of the way projects with big manufacturers turn out. The timeframe was pretty crazy – it was August when they came to see us, and they wanted to be at Le Mans the next year with a winning car called a Ford. My proposal was that we should take the Mk 6 and, without spoiling the aerodynamics, put a subtly different body on it. The project also involved a road version, which we called the GT46, because it was six inches taller to give more cockpit room for road use.

“But it all came to nothing because Roy Lunn got involved. As you would expect, Ford didn’t have a clue about what was involved in a racing car – suspension, handling, aerodynamics. They just thought it was a matter of a big engine and a slinky shape. When the initial deal was made I was going to control the design and the engineering, but Roy Lunn politicked it away from me. Lunn decided he wanted a steel monocoque, whereas the Mk 6 was aluminium. He did that for production reasons, not for strength or safety. Then they designed a body for the car with no discussion with me, just sent it over to us. High nose, low tail, hopeless. The front wheels came off the ground even after we’d modified it. The aerodynamic problems finally got through to them and they did something about it, but it wasted so much valuable time.

“I did the Ford thing for 18 months. It wasn’t all bad, we got a lot of opportunities out of it, but it could have been very different. Ford virtually took Lola over. There were a few other things going on in 1964 [F2 and F3 cars] but not a lot. There was too much of a panic and flap going on to get much else done, really.

Eric in 1958 prototype Mk1 leads Peter Ashdown’s Lotus 11 at Goodwood

Motorsport Images

Ford got me to move the Lola operation to Slough, and we had two industrial units back to back. After the split with Ford, we kept one of them.”

Independent once more, Eric stayed with the philosophy of big V8s, and for 1965 he produced the classic T70. “A lot of the Mk 6 thinking went into it. The screen height required by the rules meant we had to make the nose very low, and the Mk 6 influenced the front end a lot. We designed it as an open car and a coupé, but the open car got built first.” Through various forms up to the Mk 3B, the T70 was hugely successful in Europe and North America, usually using the Chevrolet V8, and John Surtees continued his Lola relationship by winning the first Can-Am Series in 1966. A project involving the Aston Martin four-cam V8 was less successful. “The Aston engine didn’t work out very well. It was already an old-fashioned engine when it was designed.” But the connection was to return, more than 40 years later, because an Aston Martin-powered Lola finished ninth at Le Mans this year.

One good thing that came out of Lola’s difficult GT40 episode was Indianapolis. Ford gave their four-cam Indy engine to Lotus first, but in 1965 Eric’s T80 was able to use it. “When we first went to Indy Chapman had already done two years. I felt like a new boy at the kindergarten. We weren’t quite up to speed in 1965, but the 1966 T90 was a lot better, we’d got to know the tyres and the track.” John Mecom commissioned three T90s for the Indy 500, for Rodger Ward, Jackie Stewart and Graham Hill. “Graham was very funny about the Indianapolis establishment. There was that thing about no doors in the gents’ lavatories, and when he complained that this was rather uncivilised, doors were fitted overnight. He was very critical, but everybody loved him for it. His car, in deference to its sponsor, was called the Red Ball Special. He

was funny about that, too.”

Jo Bonnier’s T70 Mk3B flies at the Nurburgring 1000km in 1969

Motorsport Images

With 25 miles to go Lolas were 1-2, Stewart leading Hill. So when Stewart’s engine failed with 10 laps to go, Hill was there to score a historic victory. Beaten into second place was Jim Clark’s Lotus: one feels that any victory over a Lotus was a particularly sweet one for Eric. “Colin Chapman and I were very different in approach, but we always got on fine. He was very clever, very good on innovation. He made mistakes, as we all did, he had good times and bad. But his cars were sometimes fragile. I was very conscious of putting people’s lives at risk. It’s not comfortable when drivers get hurt. It’s even worse when they get killed.”

All its life, racing two-seaters have been central to Lola. A new branch to the family tree came with the little T210, which used the Cosworth FVA F2 engine and punched above its weight just as the original Mk 1 had done. Larger versions followed, using the DFV F1 engine, and many variants of both strains were energetically and successfully raced by private owners at Le Mans and elsewhere.

Group 7, catering for the big Can-Am-type open cars, was an important market, and the T70 was followed by the T160 and T220 series. But in the Can-Am series itself, after Surtees’ 1966 victory, McLaren ruled. So in 1971 Lola produced the one-off T260, a dramatically blunt-nosed device, for Jackie Stewart to drive. “Jackie didn’t like it much. We were doing a lot of wind tunnel work by then, but using a tunnel without a moving road surface, and we got very seriously misled by that. If you wind tunnel test a car that runs close to the ground without a moving surface you come out with very different projections, and it wasn’t until we got moving surfaces that we made any real aerodynamic improvement.” Nevertheless, Stewart beat the McLarens to win two Can-Am rounds.

By 1970 Lola was scattered around four different locations in Slough, and a move was inevitable. Its new home was in Huntingdon, where it still is today. Eric always scoured every form of racing for possible markets, and Lolas continued to appear in confusing profusion, from Formula Ford to Supervee, from endurance sports-racing to one-make formulas. Formula 5000 grew out of the American Formula A, and with its big sports car experience Lola was ideally placed to get a car out very quickly. This was the simple, straight-forward T140.

“Frank Gardner became very involved with the 5000s. He was a brilliant development driver, and he was crucial to the T300, which was virtually our T252 Formula SuperVee chassis with a big V8 hung on the back. He won the European Championship with that. He would make some changes to a car, and find out whether they worked by going out and winning a race with it.”

When John Surtees joined Honda’s Formula 1 operation in 1967 and found the RA300 chassis compromised and heavy, he called on Broadley. “Down the years John intertwined with Lola a lot. A quick solution was needed, so basically we put Honda’s V12 in the back of an Indycar. We did it in about six weeks, got it to Monza for the Italian Grand Prix, and John won first time out. It was still meant to be a Honda, but the British press called it the Hondola, which didn’t please Honda. The following year they had their rather peculiar new V12, with a centre offtake to drive the camshafts. We did the T180 for that, which they called the Honda RA301. It didn’t really work very well.” Even so, Surtees took pole for Monza and was second at Rouen and third at Watkins Glen. After Bowmaker and Honda, Lola’s third essay into F1 was at the behest of Graham Hill’s Embassy-backed team in 1974. “Graham was not engineering oriented in any way as a driver, but he was a great guy. We did the T370 for him, which was based on the T330 F5000 car.

“Carl Haas was our American distributor, and he was very good for the company down the years. I fired him when we were getting into difficulties in the 1990s – I couldn’t work out any sensible margins with him and he just refused to negotiate. He managed to re-establish himself with Martin, so he’s Lola’s USA man again now. Carl put the Beatrice Formula 1 deal together in 1985. We did the chassis, Cosworth did the engines, but the chassis didn’t work well and the engine was no good. Then Teddy Mayer got involved and it all got split away from Lola. I’m not sure if Carl was really sold on racing around the world, he preferred things in the US. Anyway, it folded. But Carl did extremely well out of the whole thing.”

Lola supplied F1 chassis to Gérard Larrousse’s team for some five seasons, using Cosworth and Lamborghini engines. “It was a reasonable midfield operation, but things got a bit difficult when Didier Calmels, Larrousse’s partner, was arrested for murdering his wife. We also built some chassis for Scuderia Italia in 1993.

“By the start of the 1990s we’d become the world’s largest commercial racing car manufacturer, in just about every formula. We were in too much, really. When you look at it all in retrospect, you realise all the mistakes you’ve made over the years. You look at a project and realise what you should have done. I always remember the things that didn’t work so well, and forget the successes.

“We’d set up a separate composites business, but we couldn’t get it rolling fast enough. For Lola Cars to survive, I decided we either needed to do a road car, or we needed to get into Formula 1. There wasn’t anything else. A lot of other formulas were going one-make, at cut-throat prices. So in 1996 we started our F1 project, and it failed. For various reasons: I was 68 and, although I didn’t realise it, I wasn’t very well. I had a multiple heart bypass soon after that. I knew what the problems were with the car, but I didn’t have the energy to deal with them. We planned to be ready to run in 1998, but Mastercard, the sponsor, insisted that we were racing in 1997.”

It was a disaster. After almost no testing, the cars went to the opening round in Melbourne, but drivers Vincenzo Sospiri and Ricardo Rosset were more than 11sec a lap off the pace. They went to the next round in Brazil, only to be called home when it emerged that Lola’s understanding of how the sponsorship was meant to operate was very different from Mastercard’s. The F1 operation owed £6 million, and a few weeks later Lola Cars was in administration. A former customer read about the company’s dire problems, and got on the phone to Eric Broadley. By September Lola had a new owner.

Slough factory in 1968

Motorsport Images

Martin Birrane is, according to the Sunday Times Rich List, Ireland’s ninth richest man, worth some £144 million. His main business is property, but he also owns the Mondello Park circuit and a share of the Sunday Tribune newspaper. He has raced in touring cars, GTs, Formula 5000 and Formula Atlantic, and has competed at Le Mans 10 times. In 1973 his Crowne Racing Lola T292, driven by Chris Craft, won the European 2-litre Sports Car Championship.

Why did Martin buy Lola? “Because of the brand, and because I believed there was a business there. I invested a lot in it, and the first thing that came right was the CART situation. Reynard were ruling the roost there, and there were no orders for 1998. I hired Frank Dernie to look after the design side, and by 2000, with Chip Ganassi and Newman-Haas, we had drivers like Juan Montoya and Michael Andretti, and we won seven races. In 2002 Lolas won 10 rounds, and by 2003 we were dominating the series. Reynard went bankrupt in early 2002, which was actually bad news for us. Competition is what keeps this business going, keeps your engineering up there.

1958 beginnings in Bromley

Motorsport Images

“Another exciting project was the MG Le Mans programme. We wanted to make a car for the LM675 category, and there was a proposal that Lola should become part of the consortium to buy MG. Mayflower, a big motor industry supplier, were in it with us, but then they went under, which put paid to my chances of doing a road car with them.

“We had a three-year agreement with MG for Le Mans, but they pulled out after the second year. They didn’t want to use the engine we proposed, they went for a version with a little more power and a lot less reliability. The cars were quite successful later in the USA. My leaning is very much towards Le Mans prototypes. In 1998 I commissioned eight cars, and we sold them for $550,000 each, so we got back our R&D costs and a bit. Since then we’ve made a further seven prototypes, and got our costs back on all bar one. Lolas won LMP2 at Le Mans four years on the trot, and there were seven Lolas running there this year.

“Lola Composites is a crucial part of the business, doing work for the aerospace industry, the Ministry of Defence, fuselages for unmanned reconnaissance aircraft and so on. When I took over the company the turnover was just over £6 million. This year we’re projecting over £21 million – but around £8 million of that is from Lola Cars and the rest is from Lola Composites. It’s the first time the core business is less than half, because the customer racing car business is in decline. But Lola Cars will continue. It’s a business in its own right, even if it’s a very hazardous one.

“At the moment Formula Nippon is the only one-make series that uses Lola chassis. These one-make deals aren’t usually profitable, but they help the overheads. We’ve done A1GP, built 50 cars for them, and Indy Lights. We’re making a school car for a US customer, and some people in the Middle East are looking at a single-seater and a sports car for school use. We also have an income stream from our wind tunnel, and our seven-post test rig.

“For the Le Mans cars you put in an unbelievable amount of R&D up front. It can take over a year to design, do computer simulations like FEA [finite element analysis] and CFD modelling [computational fluid dynamics], then go into the wind tunnel. Eric says it’s easier these days with computers, but I wish we could turn the clock back to when you drew a prototype, made it, put it on the track and tested it. But Eric did a fantastic job all those years. Nobody could have kept any racing car firm going as long as he did if he weren’t entrepreneurial, resilient, and hard as nails.”

In its 50 years, Lola has built nearly 4000 cars, of some 240 different models. So what has been Eric Broadley’s favourite? “I usually say the T70. The Mk 6 was nice, of course, and the Mk 1 was pretty important to how my life turned out. I liked all the formulas, all the classes. Racing is always racing.

“I suppose the thing is I was able to visualise whatever I was designing or building. If I was designing a part of a car I always visualised the whole car, and it was just a matter of getting it down on paper. I don’t know where it came from. I suppose a lot of what went into the Mk 1 was intuitive. Chapman had been in the aircraft industry, I’d built some houses. If I hadn’t built the Lola Mk 1 I’d have carried on in the building business. I’ve had an amazing life, I’ve worked with some wonderful people, and I’ve been very lucky. Mostly I’ve been lucky.” And Lola is lucky to have lived for half a century: that’s thanks to Broadley and, now, thanks to Birrane.