The Aston was never designed with the Dakar Rally in mind so it ran along and up the bank, didn’t know quite what to do at the top and flipped over, trapping me underneath. The half of the car I was under was sticking into the road, well past the apex of the corner, just on the exit line, and would have been out of sight of the oncoming cars, even in daylight. The smell of petrol suggested that the options were either a cremation or a simple run-over incident. I had been party to a pretty good BRM burn-out job at Silverstone in the 1956 British Grand Prix – the car recognising its serious shortcomings and doing the decent thing – but I was in an unconscious, disinterested state beside the inferno at the time.

Consideration of the possibilities was momentarily dismissed by the Aston pressing down on me, and the thought that I had proved to my satisfaction that it was indeed a heavy car, as team-mates had been known to mumble about, but I was quickly forced to focus on the sound of fast-approaching cars.

The first one round the corner was a Porsche, fortunately driven by Umberto Maglioli, always an able and considerate driver, who somehow managed to maintain a tighter exit line than normal, striking the Aston’s tail with sufficient impact to knock it up and aside and set me free. The survival instinct overwhelmed everything and despite my shock I nevertheless managed to drag myself up the sandbank to safety and finished in the arms of a track official, who seemed as surprised and stunned as me. I shall be eternally grateful to Umberto and apologetic for the fact that my stupidity caused his retirement. Sadly he died a few years ago.

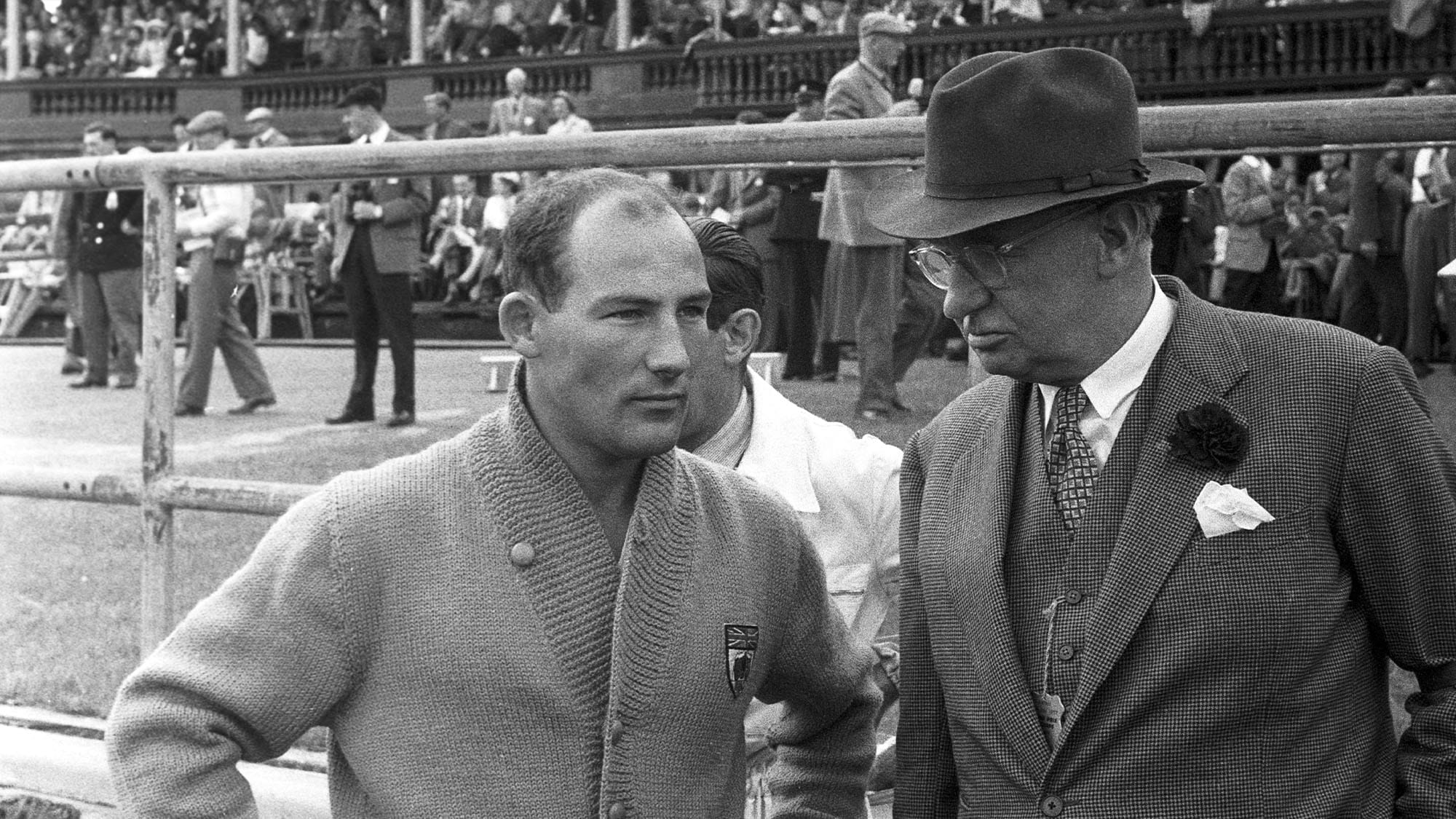

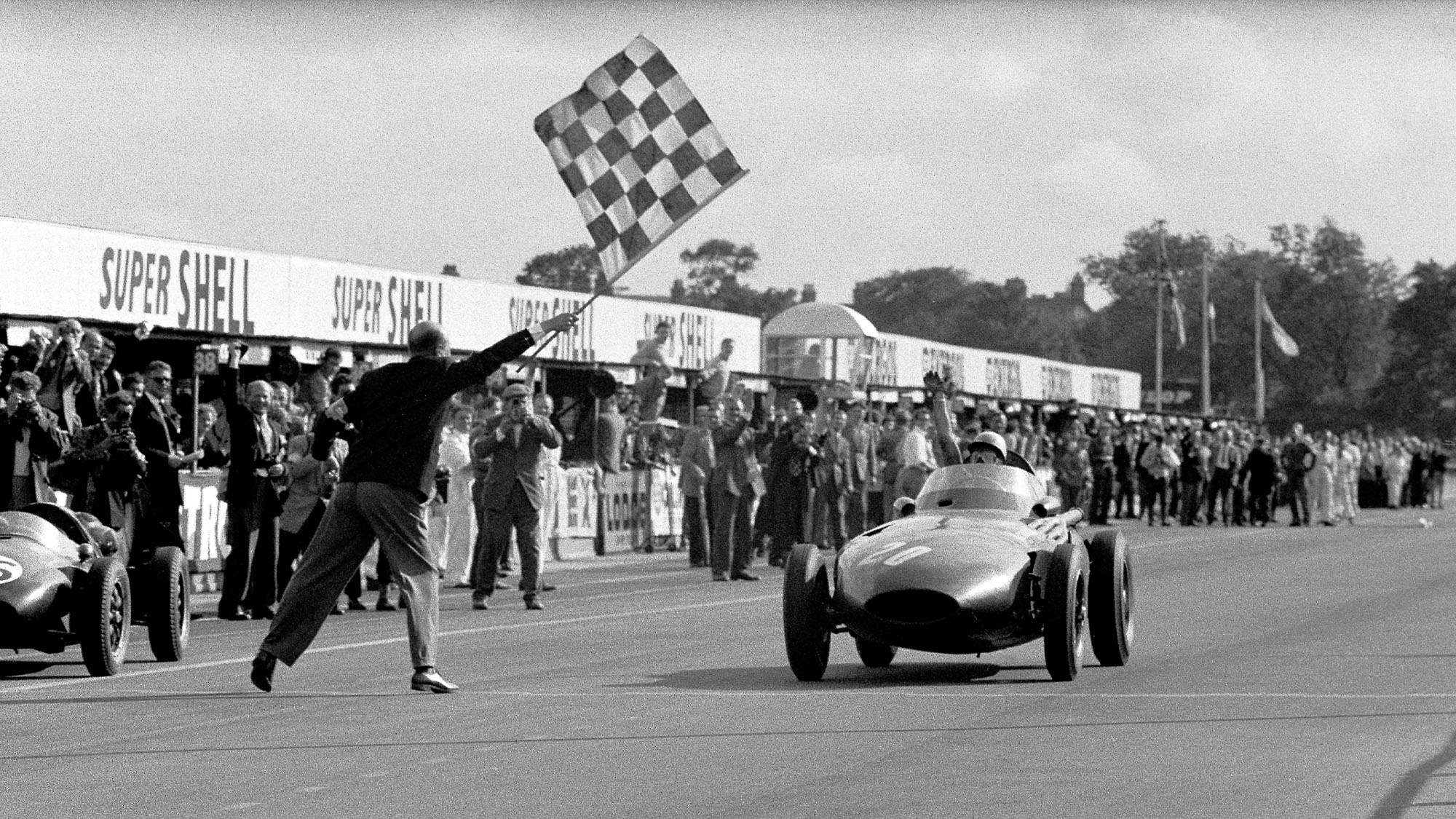

Field sets off at Aintree

Getty Images

I spent time in the Le Mans hospital before David Brown arranged for me to be flown back to England in his private aircraft. I hadn’t broken any bones but suffered severe lacerations and contusions on my arms, back and legs, with a hole in my thigh that could hold a tennis ball. I was confined to bed at home until a week before the Aintree event, and drove a car for the first time when I set out to attend the Thursday practice session in the family’s Ford.

Although I was not fit to race I managed to talk my way through the perfunctory verbal medical ‘examination’ as I could stand and do a good impression of walking normally. My team-mates were Stirling Moss and Stuart Lewis-Evans, and clearly Vanwall had a better chance of success if it started three rather than two cars, as reliability was not its strongest point. Stirling tried my car as was normal practice, recording a lap time of 2min 1.4sec, and I managed 2min 0.4sec, equalling the lap record but two-tenths behind Stirling’s pole time in a ‘new’ car, his original one being relegated to the spare.

The few feet of sorbo rubber wrapped around the seat and myself handled the pain briefly, but the race distance of 90-laps (270 miles) over three hours at a competitive speed was quite another matter, so it was agreed before the race that Stirling or Stewart would take over my car in the event of theirs giving trouble. I was nevertheless very pleased to have had the opportunity to demonstrate that my argument with the sandbank had not detracted from my driving performance, the accident being due to stupidity rather than a judgemental error, although a sharp reminder that motor racing was indeed very dangerous in those days.