Here the eager car-lover found a single-seater Talbot grand prix car — which was for sale. But at an outrageous £1200, it was out of the young Pilkington’s reach. Disappointed, he was preparing to leave the back-street workshop when he saw some blue bodywork through a grubby window. On asking, “What’s that, Monsieur?” he was taken through to inspect the distressed remains of a Talbot sportscar. Grignard explained why it was sitting there gathering dust.

He had bought it from Louis Rosier, the privateer Talbot campaigner, in 1953 and entered it in the 12 Hours of Casablanca. Thanks to an inexperienced co-driver they ran out of fuel. Grignard then decided to enter it for the 1954 Le Mans, with Guy Mairesse as co-driver and, as a shakedown, the pair planned to contest the Coupe de Paris race at Montlhéry. Which is where it all went wrong. During a practice session, Mairesse found a little Renault stopped right on the racing line in a fast corner, and had to swerve. He went off at high speed through a line of concrete posts, killing a six-year-old boy and fatally injuring himself.

In this damaged state, the car had sat for the last four years as the legal aspects were sorted out. Now Grignard was ready to sell, but Pilkington had already stretched himself with his pre-war Alfa, and even this wreck was more than the £16 he had put aside to get himself and Alfa to Le Mans and back. It was lucky that Pilkington Snr was a Talbot enthusiast and could be persuaded that this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity…

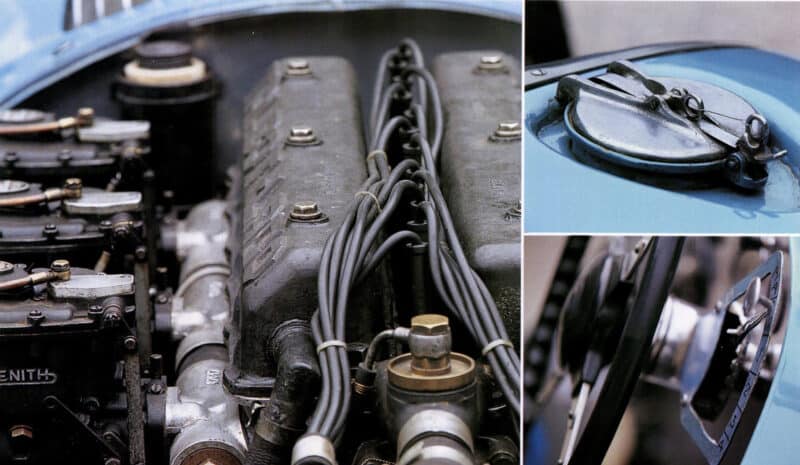

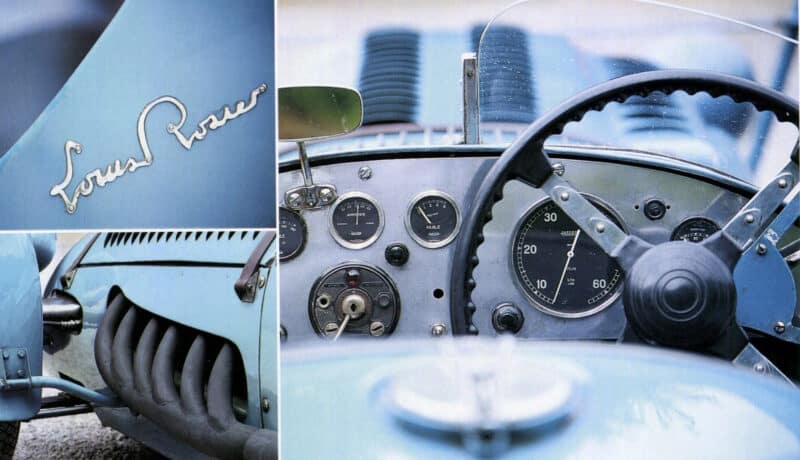

One famous owner — Louis Rosier bought car from works; dash was unaltered when body widened; front suspension as robust as six-cylinder motor

Charles Best

Back in Britain after Le Mans, with a deal done, Richard suddenly had a new problem. In the 1950s, importing a car to the UK was far from easy; a cash-strapped and war-ravaged economy wanted to sell its own cars, not buy someone else’s, however old and damaged. Trying to clear the way in advance was bound to get bogged down in paperwork, so Richard decided on the full-frontal approach: he would drive it back to England and bluff it out with Customs. Easy. Except that the body was torn and flapping, and the engine had been taken out and disassembled.

Grignard agreed to allow Pilkington to use his workshop, and to loan Claude, his racing mechanic. So the following Easter, Richard set off for Paris in his MGA “with a few tools and useful-looking hammers”. Claude had already begun the engine work, so Richard began on the battered body, cutting away the loose bits and folding the sharp edges back, adding some running lights at the front, replacing the punctured rad from Grignard’s spares, and “generally hammering things a bit straighter”.

This was not repair work by any stretch of the imagination; when the Talbot, its drivetrain now running remarkably well given its hibernation, finally bellowed out of the little garage, everything ahead of the cockpit was bent, the offside panels were missing, a wheel spun nakedly in the wind, and everything flapped. You’d think even the French police might have something to say, but no. With the MGA behind to collect anything that fell off, they plunged into the Paris traffic.