“We knew about it,” admits Cooper. Didn’t get round to telling the Richmond boys, though. That’s called knowing which side your bread is buttered. “That gave Mike an extra 15bhp. But he did the rest. You could see by the way his car leaned through the corners that he was working it harder, getting more from it, than the rest.”

It wasn’t just a case of being quicker down the straights. “Mike just got in and drove. Stilling tended to alter things; he should have won the world championship, but a lot of it was his own fault with the wrong decisions he made about the set-up of his cars. Mike was the opposite.”

Cooper appreciated that the Ecurie Richmond squad had raced his nimble 500s, and so disliked his new car’s lack of brakes, moaned about its lack of power (no nitro, you see), and struggled with a change of direction that was sluggish compared to what they were used to. Mike just knew it was a damn sight better than his old Riley. While Moss was, at best, marking time in the ‘cutting-edge’ G-Type ERA, Mike was going gleefully sideways and forging ahead. A brief test at Lasham Aerodrome, an all-nighter to recut warped valve seats, another Lasham run, and he was ready. For what, exactly, he wasn’t quite sure.

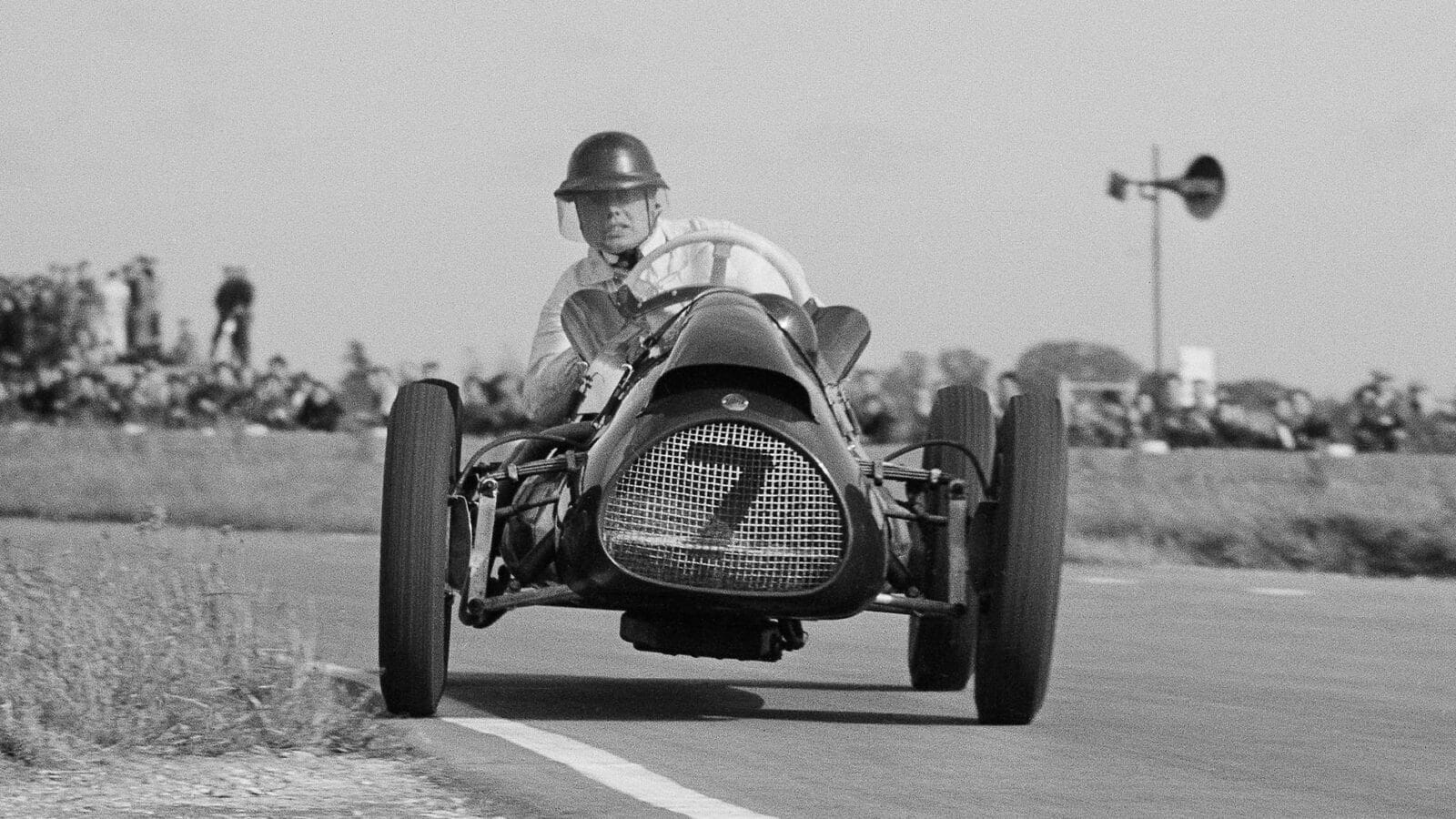

What he got was second-fastest lap during Saturday practice for Goodwood’s Easter Meeting, beaten only by the ’51 British GP winner, Froilan Gonzalez, in the 400bhp Thinwall Special. Mike would, therefore, start the F2 Lavant Cup from pole. Brand new car, brand new driver (as near as damn it), yet the rest of Britain’s expanding racing fleet was floundering in his wake. What’s more, world champion Juan Fangio, waiting in vain for the arrival of his too complex, too non-Cooper, V16 BRM, was watching from the sidelines and from the cockpit, once he’d sidled over to Cooper’s pit and been asked if he’d like a drive.

Easter Sunday was a day of rest: 24 hours for Hawthorn to ponder the enormity of achievement and what was still to come. It was, it seems, hardly a nervous wait, though. He came through it all with flying colours. Having made a calm getaway in his first ever single-seater race, the six-lap Lavant Cup on Easter Bank Holiday Monday, he disappeared, finishing 22 seconds (in a 10-minute race) ahead of Brown and Brandon. He repeated the dose in the Formula Libre Chichester Cup, while Fangio, having his only Cooper-Bristol outing, finished way down with engine problems. By way of a curtain-closer, Mike finished second in the headlining Richmond Trophy, giving spirited chase to Gonzalez.

He’d arrived a novice, departed a star. The morning papers were awash with his name, reporters were beating his door down. A few years later they would be dogging his every footstep, damning his every move, but right now, he was the handsome, carefree hero who’d just beaten the champion, in the exact same car, on his single-seater debut.