From studying the catalogue beforehand, I was only too aware of what was on offer here. Neubauer was clearly a hoarder of some consequence, keeping such as armbands and posters and programmes, as well countless photographs, many in dedicated albums, many signed by the great drivers of the day. The volume of the collection was breathtaking in itself.

Merely being in the presence of such a slice of motor racing history was a faintly surreal experience. On a sunny morning, I walked into the Jack Barclay Showroom in Nine Elms, made my way between the Rolls Royces and Bentleys and there it all was. To the left, in a glass cabinet, Rosemeyer’s linen helmet, to the right bronze models of the Mercedes W125 and W196, a silver cigarette case from von Brauchitsch, a crystal glass cocktail shaker from Lang…

Through all his long years in the sport, though, undoubtedly Neubauer’s favourite driver, and the man he considered the best ever, was Caracciola. Never completely fit after suffering terrible leg injuries at Monaco in 1933, Rudi’s innate genius remained, and in the wet, particularly, none could touch him.

If his skills were intact, however, the years inevitably pared something from the edge of Caracciola’s commitment, and by the late 1930s he was invariably outpaced by Lang, the mechanic who became one of the very greatest drivers, and whose best years were lost to the war. Neubauer, Caracciola’s firm friend, well knew what was happening, but was aware, too, of Rudi’s enormous contribution to Mercedes success down the years, and never threatened his dignity.

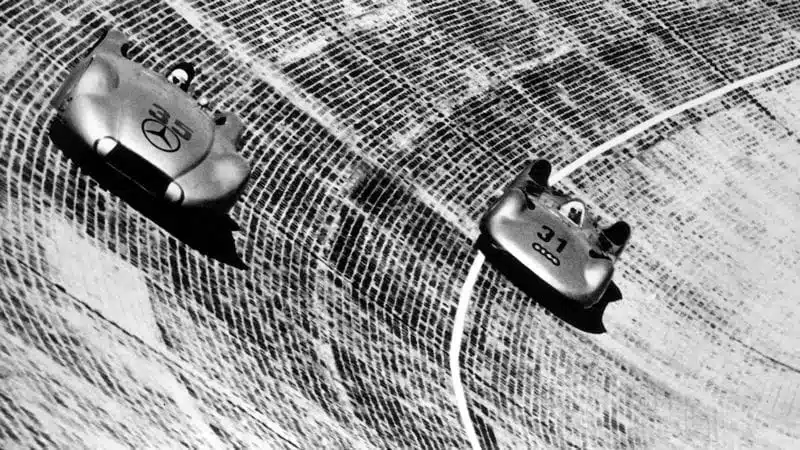

Caracciola (Mercedes) and Rosemeyer (Auto Union) duel at Avus as they did for much of the 1930s

ullstein bild via Getty Images

Lang, right to the end of his days, maintained that Neubauer had shown favouritism to Caracciola, and Karl Kling, a member of the Mercedes squad in the ’50s, supported him. “Undoubtedly,” Kling said, “Lang was often not allowed to drive as fast as he could. You could write a novel about what went on in those times…”

Whatever, Caracciola dearly appreciated his friend Neubauer. Among the items I studied was a photo album signed and dedicated to him in 1936. Among Neubauer’s most treasured possessions, it was not a surprise to see it valued at around £5000.

For a time there was also a feud between Caracciola, the old master, and Rosemeyer, the young pretender, but Neubauer relates that this was finally resolved over a bottle of champagne at the Roxy Bar in Berlin. Civilised times, were they not?