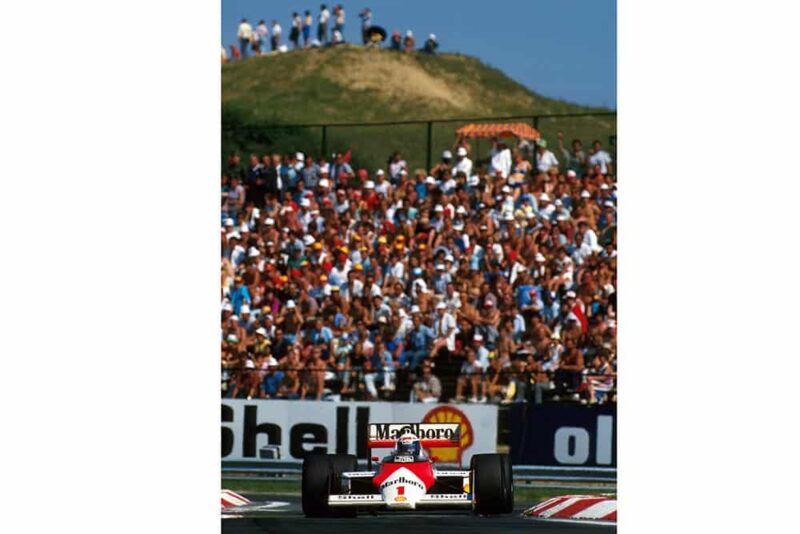

Formula One: 1987 Hungarian GP

Winner Nelson Piquet in his Williams FW11B.

© Motorsport Images

Favours of fortune

Within a period of two weeks Nelson Piquet led less than 30 miles of Grand Prix motoring — but bagged 18 points in the 1987 World Drivers Championship as a result.

What made his second lucky win so ironic was that it came two days after he told the Williams team he would be leaving it at the end of the season to join Lotus. Moreover, his stated reason for leaving Williams is that they will not adhere to his contract as number one driver and force Nigel Mansell to play second fiddle to his World Championship aspirations. After his win in Hungary it is possible that he will win the world championship anyway, without Mansell’s acquiescence!

Nigel Mansell (Williams FW11B Honda) leads Gerhard Berger and Michele Alboreto (both Ferrari F187’s), Nelson Piquet (Williams FW11B Honda), Alain Prost (McLaren MP4/3 TAG Porsche) and Ayrton Senna (Lotus 99T Honda) at the start.

© Motorsport Images

One of the idiosyncracies of Motor Sport is that DSJ and I share the burden of writing Grand Prix reports; consequently you will find different prejudices reflected in different reports, depending on which of us is behind the keyboard. This year’s Hungarian Grand Prix report is a classic example of that divergence of opinion. Whilst we agree on most fundamentals about Grand Prix motor racing, equally we are poles apart on some of the details.

As you will have gathered from DSJ’s British Grand Prix report, he is an avid Piquet fan. I make no such claim, and therefore believe that the Brazilian driver’s wins at Hockenheim and, more particularly, at the new Hungaroring, a few kilometres outside Budapest, amounted to two of the biggest slices of luck he will ever receive. The drivers who handed him these wins were Prost (at Hockenheim) and Piquet’s team-mate Nigel Mansell in Hungary.

As I strode off the plane at Heathrow the day following Nelson’s second win, Jenks was there to meet me. He greeted me with the words, “Mansell is a born loser, you see?” I think I told him to get stuffed, or something like that, in the heat of the moment; but on reflection Nigel’s loss of a wheel retaining nut with only five of the race’s 76 laps left to go, whilst nursing a commanding lead, ranks as one of the most remarkable retirements of recent years.

Nigel Mansell, Williams FW11B, leads the field away on lap 1.

© Motorsport Images

He had started from a commanding pole position, held off a fleeting challenge from Gerhard Berger in the Ferrari F187 which faded after 13 laps when the Austrian retired with transmission failure, then dominated the race, until his retirement.

Piquet qualified third, ran fourth almost from the start, moved up to third on Berger’s retirement and finally wrestled his way past Michele Alboreto’s sister car on lap 29. Thereafter he settled down into second place, snipping the odd few fractions off Mansell’s advantage as they threaded their way through slower traffic on this tight little circuit on which overtaking is quite difficult, until, by his own admission, settling for second place in the closing stages. “My car had developed such a tyre vibration and I thought it was going to shake itself to pieces,” he said, “so I figured that I would be satisfied with second place.”

Mansell set his pole position time in first qualifying on Friday, the session starting with a wet track after an earlier shower. He swapped quickest times with Alain Prost’s McLaren-TAG, but clinched the matter beyond all doubt a few minutes from the end with what stood as pole position time throughout Saturday’s timed session, which took place in the dry. Mansell wasn’t quickest on the second day, a locking brake pitching him into a quick spin which spoiled one of his fast runs, so Gerhard Berger topped the time sheets, although his best was not good enough to dislodge the Englishman from pole.

2nd place Ayrton Senna in his Lotus 99T.

© Motorsport Images

It was the first time that a Ferrari had been on the front row of a Grand Prix starting grid since Johansson qualified second for the 1985 German Grand Prix at the new Nurburgring. The Italian team was under the technical control of Harvey Postlethwaite in Hungary, John Barnard staying home at his technical studio near Guildford where he is designing the new normally-aspirated 3.5-litre V12 Ferrari F188 which will almost certainly be raced by the team in 1988.

However, much of the current car’s improved performance stems from a number of detailed improvements effected under Barnard’s direction and fed into the racing team’s production system over the past few months. Although Alboreto eventually joined Berger in retirement, the Italian’s car suffering engine failure, there was certainly a fresh sense of optimism in the Ferrari garage which has been missing for some time.

Although his lawyers had formally advised Team Lotus that he was taking advantage of the “unconditional release clause” in his contract and, consequently, would not be driving for the team in 1988, Ayrton Senna’s committed sense of professionalism never wavered all weekend. Saddled with a car incapable of racing the Williams-Hondas on equal terms, you might have expected both Senna and Lotus to have gone slightly off the boil in the wake of the decision to part company. Not so.

Alain Prost finished 3rd in the McLaren MP4/3.

© Motorsport Images

Lotus had produced revised bodywork for the 99T, the engine cover and side pods slightly lowered, the cockpit lip cut away in more pronounced style, and Senna confessed that, yes, it was definitely an improvement. “But it’s not aerodynamics that are the problem here on this surface,” he explained, “it’s mechanical grip — and we haven’t got much of that!”

Senna also had problems with the FISA boost-control valve blowing off prematurely, so under the circumstances he did well to qualify sixth behind Prost and Alboreto. In the race he spent many laps fending off a firm challenge from Thierry Boutsen’s Benetton-Ford B187, the Belgian never quite managing to get close enough to make a decisive overtaking manoeuvre.

Towards the end of the race Boutsen dropped away with loss of turbo boost pressure, allowing Senna to finish second, the Brazilian troubled by a such a severe tyre vibration that his back was badly bruised when he climbed out of the car. World Champion Alain Prost was in trouble from the start. The alternator belt breakage which had caused his retirement at Hockenheim was a frustrating mechanical failure — the frustration heightened when the same car was taken to Silverstone a couple of days after the German race and, with nothing more than a new belt fitted, ran perfectly in the hands of Stefan Johannsson. Redesigned pulleys and double ‘vee’ belts were fitted to the TAG-engined cars in time for Austria, but Prost’s car was misfiring as early as the warm-up lap.

Nigel Mansell (Williams FW11B) retired from the lead of the race when the right rear wheel nut fell off on lap 70.

© Motorsport Images

A new control box for the Bosch Motronic engine-management system was fitted on the grid, but that did not cure the trouble and, when Johansson overtook his team leader early in the race, it was clear that Prost’s car was still not running properly. On lap 15 Johansson’s McLaren suddenly spun when its transmission seized, forcing Prost into lurid avoiding action which lost him 10 seconds by the time he had regained his momentum. For much of the race he languished in fifth place, but he slipped past Boutsen as the Benetton began to slow, at least earning a place on the rostrum for third at the finish. At no time did the McLaren-TAG combination look as impressive as it had done in Germany a fortnight earlier.

This extremely processional race provided Riccardo Patrese with his first top-six finish of the season, his Brabham-BMW BT56 ending a steady fifth after a hearteningly trouble-free run, although team-mate Andrea de Cesaris retired with gearbox trouble after an earlier pit stop to change a blistered tyre.

Christian Danner in his Zakspeed 871.

© Motorsport Images

Derek Warwick, feeling like death warmed-up owing to a nasty bout of flu and conjunctivitis, managed to grasp the final championship point for sixth, separated from his eighth-place team-mate Eddie Cheever by Jonathan Palmer’s Tyrrell, which won the naturally-aspirated class.

For the Arrows team the Hungarian Grand Prix must have seemed like a bad dream, for on this rare occasion when its two cars displayed perfect mechanical reliability, Cheever managed to drive into the back of Warwick when they were running eighth and ninth. Warwick radioed he was coming in for tyres after recovering from the resultant spin, but Cheever (whose radio was not working) beat him to it. Then Warwick arrived a few seconds later and Eddie was waved back into the race before his damaged nose cone was replaced.

The American thus had to stop again a couple of laps later for further surgery, dropping him out of the top ten. He sped back to eighth place and Warwick got on with the job of salvaging his sixth-place finish without any further assaults from behind. “Without that, I reckon we could have been fourth and fifth,” said their despairing team manager Alan Rees.

In the non-turbo category Philippe Streiff did a good job, qualifying fourteenth overall on this twisty circuit, but it was Ivan Capelli’s March 871 which took command at the start, chased hard by the Frenchman.

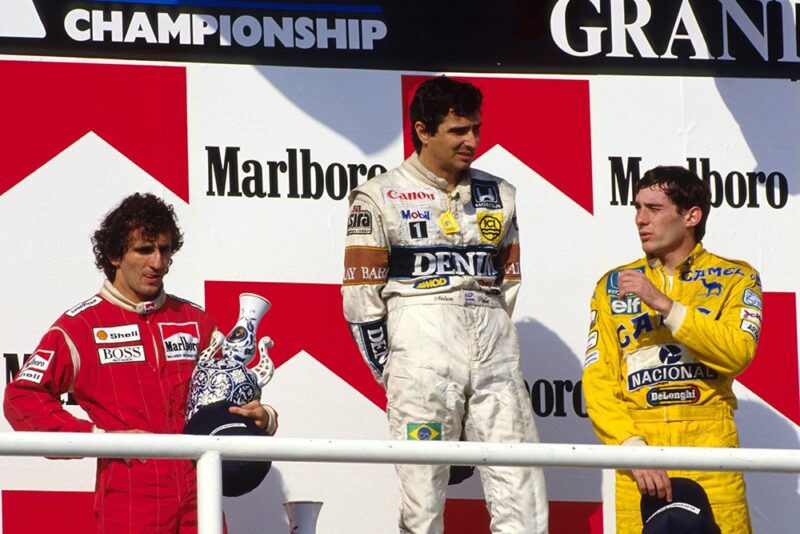

Nelson Piquet (1st) middle, Alain Prost (2nd) McLaren, left and Ayrton Senna (3rd) right on the podium.

© Motorsport Images

Goodyear had advised the non-turbo runners that there would be no problems at all with tyre wear at this track and, indeed, the biggest problem for these lightly-loaded cars was working the rubber up to its correct operating temperature. Capelli and Streiff unfortunately went too hard, too soon, and blistered their left front tyres as a result. That allowed Palmer, who had run a more prudent pace in the early stages, to move through and win the class easily, once he had forced his may past his team-mate in determined style.

Capelli finished tenth behind Streiff, whose Tyrrell was further hampered by a fractured exhaust in the closing stages, while Alessandro Nannini’s Minardi M186 was eleventh ahead of Piercarlo Ghinzani’s Ligier and the AGS of Pascal Fabre.

It was Nelson Piquet’s second successive Hungarian Grand Prix victory, but this was far less convincing than his 1986 triumph, when he slogged it out with Senna in a straight fight for the lead. More interestingly for those who love statistics, it was his 19th Grand Prix victory in 134 races. AH