1983 German Grand Prix race report

Rene Arnoux claimed a fourth career win in the Ferrari

Motorsport Images

Not very exciting

Hockenheimring, August 7th

I am sure that anyone who loves motor racing as much as I do will agree that the concrete stadium at Hockenheim has never done very much for them as a venue for the Grosser Preis von Deutschland. After the Formula One circus “chickened-out” of the Nurburgring in 1977, because it was too difficult (not too dangerous), the German Grand Prix has become a Formula One event, rather than a Grand Prix and in much the same way as happened in Belgium when their Grand Prix went from Francorchamps to Nivelles and Zolder, we have been attending the German Formula One race at Hockenheimring and “treading water” in the hope that sanity would return. We kept the faith in Belgium and it paid off, with a return to a rejuvenated Francorchamps circuit this year. We have been keeping the faith in Germany and now work is forging ahead on a new Nurburgring, and while a return to the Eifel mountains in 1984 seems a little unlikely, it must surely happen in 1985. It is anticipation that keeps some of as going, and those who keep the faith are seldom disappointed. We kept the faith with the Austrian enthusiasts when they held races on the Zeltweg airfield, and they gave us the magnificent Osterreichring, so it does pay to keep the faith. Should this prove to be the last visit to Hockenheim there will not be too many salt tears left behind.

Patrick Tambay took pole in his turbo-powered Ferrari

Motorsport Images

It was grey and foreboding as we drove down the famous Frankfurt-Darmstadt Autobahn, pausing at Langen to pay our respects at the monument to Bernd Rosemeyer who was killed on this Autobahn in 1938 attempting records at over 270 mph in an Auto Union. At Hockenheim the greyness did not improve and even Heidelberg was wet and soggy. For Friday morning’s untimed test session the scene in the pits reflected the ominous sky, which was grey and troubled though not actually raining.

Everyone was there who had been at Silverstone for the British Grand Prix, with only one new car (from Alfa Romeo) but quite a number of detail changes and improvements, like the more complicated rear aerofoil arrangement on the spare Toleman-Hart, a longer wheelbase on the newer of the two Spirit-Hondas; some Goodyear dry-weather race tyres of radial construction, rather than cross-ply, a lot of new advertising on the Arrows, but bad words like Marlboro, John Player and Gitanes were blanked out on cars, drivers, transporters and mechanics of other teams, as Germany forbids cigarette advertising at sporting events. There were small Italian flags on each side of the Ferrari cars, and a written statement from Ken Tyrrell saying that he now had the support of Frank Williams in his protest about the water-injection being used by Ferrari and Renault on their turbocharged engines.

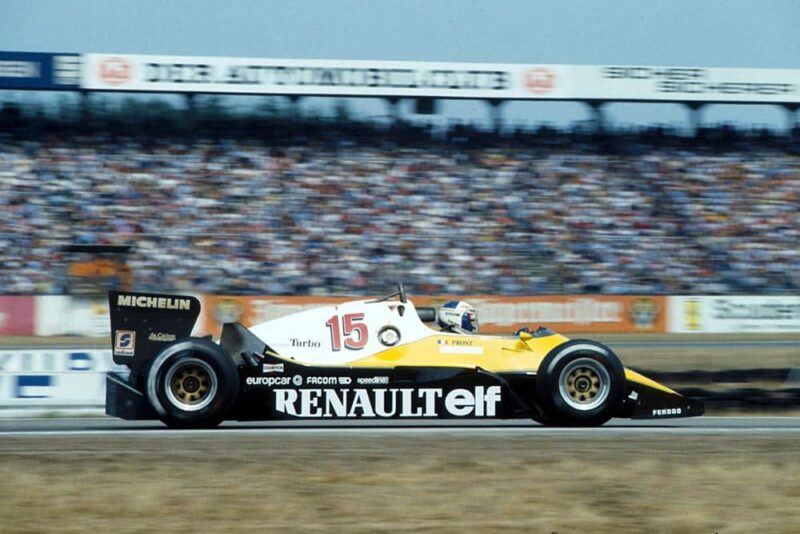

Alain Prost, Renault RE40, who finished 4th.

Motorsport Images

There seemed to be more trouble in the first hour and a half than we have seen all season, with the Honda power from the V6 engine twisting the pinion gear off the Hewland mainshaft on the newer car, oil feed and turbo trouble on the number one ATS, water leaks on Mansell’s Lotus-Renault 94T, a bent front end on the sister car when de Angelis went off the road, electrical trouble and engine troubles in the Brabham pits and engine problems in the Toleman camp. And this was only a test session in preparation for the serious business of qualifying in the afternoon. The Ferrari team and the Williams team were trying the Goodyear radially constructed race tyres, without coming to any definite conclusions and the Alfa Romeos were going quickly, but not as quickly as the time-keepers thought at one point in the morning.

Qualifying

When qualifying began at 1 pm a number of drivers, like Warwick, Johansson and Winkelhock, were nothing like ready to go out, or to be more precise, they were ready but their cars were not, while others like Piquet and Mansell were out on the circuit but soon in trouble. In the Ferrari pits all was remarkably well under control with Tambay setting the pace on Goodyear “one lap specials” which destroyed themselvee in one fast lap, but as that lap was FTD and pole position, nobody worried. Arnoux was running on harder tyres that were raceworthy and was second fastest and very close to Tambay and both cars, which were the C3 models used at Silverstone, were behaving impeccably, so much so that the pair of C2 models acting as T-cars were never even started up.

Keke Rosberg was 12th fastest in his Williams

Motorsport Images

From the word go it was a Ferrari day, and both drivers got below 1 min 50 sec for the lap, while the nearest challenge came from de Cesaris with one of the Alfa Romeo V8 cars with 1 min 50.845 sec, a second and a half slower than Tambay. Renault were not happy, with little niggling troubles, and Prost could do no better than fifth, but Piquet had his Brabharn-BMW in fourth place, in spite of having to change to the spare car. Warwick and Giacomelli were in a pretty healthy ninth and tenth positions and Johansson got the older Spirit-Honda into 13th place in spite of all manner of small troubles. The Lotus-Renault cars were into much trouble that the team was in the running for the “Team Shambles” award, while Brabham were strong runners-up, only saved by Piquet going very fast when things were right, which was not often. Halfway up the list, or down the list depending on how you look at it, was the cool and quiet Thierry Boutsen in an Arrows, only Rosberg being faster among the Cosworth V8 engine users. During the qualifying hour Raul Boesel had a nasty accident when he went off the track in the spare Ligier within the stadium and damaged his neck. Before the end of the hour a cool wind had got up and before the end of the afternoon it was raining.

On Saturday morning it was still teaming and there was no meteorological hope of it giving up. Although testing time carried on as usual on Saturday morning and the qualifying hour ran its course in the afternoon, the grid positions were decided by Friday’s performances, with the two Ferraris on the front row. On Friday Acheson (RAM-March) and Fabi (Osella-Alfa Romeo V12) had failed to qualify because they were not fast enough, and Manfred Winkelhock (ATS-BMW t/c) had failed to record a flying lap, so it was now all over for them and the troubled ATS team had to suffer the ignominy of not taking part in their home Grand Prix. Many of the others went round in clouds of spray, the scrutineers reprimanded some teams for having inadequate obligatory red rear lights, some drivers did but a single lap so were not timed and others did not go out at all, as the practice-times table shows.

Brabham’s Nelson Piquet was 4th on the grid

Motorsport Images

If you don’t do three consecutive laps you don’t get timed for a flying lap and the timing mechanism does not register a standing-start lap from the pits, nor a lap on which you come into the pit lane, so a driver could be in and out of the pits all day and not record a flying lap. It may have been wet and slippery, but on racing wet-weather tyres today’s racing driver still goes incredibly quickly and Cheever and Arnoux recorded laps in the 2 min 09 sec bracket, only eight and a bit seconds slower than Fabi had managed in the dry, and I doubt whether the average sporting club driver could manage 2 min 19 sec in the dry.

It was still raining when the qualifying hour finished, leaving the two Ferraris strongly on the front row of the grid followed by the Alfa Romeo of de Cesaris, the Brabham-BMW of Piquet and the two Renaults of Prost and Cheever, and then Baldi’s Alfa Romeo. It was the big manufacturers hard at it agin. As darkness fell depressingly early in Germany it was still raining, and when we woke up on Sunday morning it was still raining.

Race

As the lights go out, Tambay leads Ferrari stablemate Rene Arnoux as the lights go out

Motorsport Images

By the time we got into the dank concrete stadium the rain had stopped and the speed with which the ground was drying out was most encouraging. As the skies turned from dark grey to mid-grey there was hope, not of a scorching summer afternoon, but at least a dry one. Competitors in one of the many supporting races damaged the catch-fences in places so the Formula One half-hour warm-up was delayed from 11.30 am to mid-day, while repairs were effected. From midday for the next 30 minutes you have never seen so much concentrated trouble among the teams.

The half-hour warns-up period is supposed to be no more than what it says, but it turned out to be something of a mechanical destruction derby as everything went wrong. Before it was over Tambay was out in his old C2 Ferrari while eight Ferrari mechanics set to work removing the engine from his C3 Ferrari as it had suffered mechanical damage inside, and it was a brand new one only installed the previous evening. In the Renault pits the engine in Prost’s car was being removed as it had started to overheat violently, and another new one was being installed. Team (Shambles) Lotus were no better off as the 94T of Mansell had blown all its water and a lot of its oil out, all over the Spirit-Honda which had been following, and the 94T of de Angelis had stopped abruptly when the electronics for the fuel-injection had failed. While this in itself was not disastrous it meant that the oil pumps suddenly ceased their flow and with the turbocharger turbines running at over 100,000 rpm it spelt disaster for the central bearings on the turbine/compressor shafts. By the end of this warm-up period the Brabham pits looked like a major disaster area with all three cars torn apart and bits everywhere.

Formula One regulations stipulate that there must be 21/2 hours between the end of warm-up and the race starting, unless everyone is ready before that period of time and are agreed to shorten the gap. On the face of it the start should have been delayed until 3 pm, but the great god television was dangling from his satellite in anticipation of a 2.30 pm start, as advertised in the programme. A quick walk along the pit lane made it seem very unlikely that all the cars would be screwed back together in time, but it never ceases to amaze me just how much work eight or 10, or even 12 mechanics can accomplish. The pit lane should have opened at 2 pm to let the cars set off on their lap round to the starting grid, and many of the teams like Toleman, Tyrrell, Arrows and Williams were all ready to go. While the television moguls bit their nails the army of mechanics did wonders and at 2.10 pm everyone was ready, or as ready as they could hope to be. Tambay’s C3 Ferrari was ready, Piquet had chosen the spare car from his two Brabhams, Rosberg was in his regular race-car number 07, but Mansell was forced to take the 93T Lotus, rather than his Silverstone 94T. On his way round to the grid Prost found his new engine was overheating badly, suggesting an installation fault somewhere, and he went back into the pit lane and transferred to the spare Renault.

Tambay leads before being overtaken by Arnoux

Motorsport Images

By 2.30 pm they were all on the grid, where they should have sat for the regulation 20 minutes while pre-race formalities are concluded, but by mutual consent and everyone being ready this time factor was halved which reduced the overall delay to manageable proportions. The 26 cars went off on the parade lap with the two red Ferraris leading, watched by a packed stadium of people and in the pits was Didier Pironi, still on crutches, but looking remarkably fit, this being his first public appearance since his awful accident at the Hockenheimring exactly 52 weeks ago. The crocodile of cars wound its way back through the twists and turns of the stadium and lined up on the starting grid, were given the green light and all 26 drivers stamped hard down on the accelerator pedals. There had been a feeling that de Cesaris might do another screaming start, as he had done in the Belgian GP, and take the lead from the two Fermis, but it was not to be and when the field returned to the stadium the order was Ferrari, Ferrari, Brabham-BMW. Tambay led from Arnoux, Piquet, de Cesaris, Prost, Cheever, Baldi, Patrese, Johansson, Rosberg and Warwick, but already Guerrero had stopped with a blown-up Cosworth engine in the Theodore and on the next lap the Renault engine in Mansell’s old Lotus expired.

Tambay was all for choosing a pace that would not stress his car or his tyres and yet keep the two Ferraris just out of reach of Piquet’s Brabham, but Amoux had other ideas and on lap three bludgeoned his way by his team-mate and went off into a commanding lead, much to Tambay’s consternation as he saw Arnoux kerb-jumping and working his tyres unmercifully. Alboreto pulled his blown-up Tyrrell off onto the grass and the second Lotus ran into engine trouble, and then the second-place Ferrari went sick. An unheard of engine failure saw Tambay completing a slow lap and disappearing into the pits. He did one more slow lap and then retired with suspected valve trouble in the Ferrari engine.

Keke Rosberg pits on his way to 10th

Motorsport Images

This left Arnoux with a commanding lead over Piquet, and really there was no one else seriously in the race. Prost, Cheever, Patrese and de Cesaris followed in line-astern formation, but too far back to be of any real significance and then came Warwick leading Baldi in the second Alfa Romeo. Johansson was hanging on to the end of the turbocharged trail and looking quite encouraging for a new project, and Niki Lauda was showing what he is really made of by leading all the Cosworth powered cars. It was vintage Lauda and good to see.

The race was being run over 45 laps and at quarter distance it was really all over as far as serious racing was concerned. It was just a matter of Arnoux and Piquet being careful as they began to lap the tail-enders, especially Piquet remembering his nonsense with Salazar last year at this circuit, and of keeping going until the mid-race pit-stops were due. While Warwick was holding his own with the tail-end of the turbocharged cars his team-mate Giacomelli was in trouble with a failing turbocharger and only sufficient boost to allow him to keep station with the lesser Cosworth-powered cars. The Honda had expired and then when we thought Warwick might be stopping early for new tyres and more fuel he was actually stopping for good with engine trouble.

Prost was the first to make a routine pit stop, pulling out of third place to turn into the pit lane. He was far from happy for his gearbox was continually jumping out of top gear and first gear had broken on the start line, so after a refill and new tyres he was forced to make a slow start in second gear. Not long after rejoining the race top gear broke and he was limited to peak rpm in fourth gear, which held his speed down on the fast straights, and after rejoining the race in sixth place he could make no further progress up the field.

Riccardo Patrese took home 4 points with 3rd place

Motorsport Images

Nearly a lap behind, Rosberg was also far from happy for he had chosen a different type of Goodyear tyre to Laffite and had found he could not keep up. He made his routine pit stop and set off on a different type of tyre, but it did not seem to make much difference and time lost in getting into gear after his stop put him a lap behind the leading Ferrari. We were now at half distance and as Arnoux stopped, Piquet and Cheever went by, temporarily, but Cheever stopped on the next lap which meant that Arnoux was now in second place, but not too worried for Piquet had yet to stop. The Alfa Romeos, the McLarens and Laffite all made their routine stops, with Lauda showing how not to do it by sliding past his pit with his front wheels locked up. He reversed back and was subsequently disqualified for the action.

Neither Brabham had stopped and we wondered if Gordon Murray was pulling a crafty trick by running his cars through non-stop when everyone else had stopped. At the end of lap 28 there was universal relief as Patrese pulled into the pit lane, having gone eight laps further than Prost, for example. The Brabham mechanics excelled themselves and Patrese’s car was stationary for a mere nine-and-a-quarter seconds, during which time all four wheels were changed and petrol was pressured into the tank. This was nearly two seconds quicker than the best of the opposition and nearly four seconds quicker than most teams. Piquet continued to circulate until lap 30, a full 10 laps more than the first Renault that stopped and seven more than Amoux’s Ferrari. It was now clear what was happening. As the art of wheel-changing has become perfected it has become obvious that the time-limiting factor was the speed of putting petrol into the tank, or expelling the air in the tank. If, for example, the wheel-changing was going to occupy 10 sec. and the refuelling was going to occupy 12 sec, you needed to find a way of saving two seconds on the refuelling. If it was not possible to increase the flow through the petrol filler nozzles, there was only one solution and that was to put less fuel in, in other words only 10 sec-worth of fuel instead of 12 sec-worth. And if 10 sec-worth was not enough to cover half the race the solution was to start with more petrol and run beyond half distance to the point were 10 sec-worth of petrol would see you through to the finish, thus reducing your pit-stop time to the time needed to change wheels. It had worked perfectly with Patrese’s stop, with the 9.25 sec result, but was not quite so good with Piquet, his stop taking 11.12 sec, still faster than anyone else, and two seconds faster than Arnoux. But the Ferrari had built up too much lead in the early stages, so the calculated change of tactic didn’t work, but nonetheless it was an interesting time-and-motion study, and livened up a rather dull race.

Rene Arnoux (1st place) flanked by Andrea de Cesaris, left, 2nd place and Riccardo Patrese

Motorsport Images

Apart from Prost being in trouble with his Renault gearbox we were back to square one after all the stops, with Arnoux comfortably ahead of Piquet, with Cheever third, Prost fourth, de Cesaris fifth and Patrese sixth. Everyone else was a lap or more behind and being led by Lauda, followed by Watson, Laffite, Surer, Jarier, Boutsen and Rosberg. Cecotto and Sullivan had been having a nice little dice together and Ghinzani was a lonely last. Prost fell back behind de Cesaris and then Patrese, and Arnoux began to ease up as the end was in sight. On lap 39 Cheever’s excellent third place went out of the window when his Renault engine died on him due to the throttle mechanism breaking.

With only three laps to go misfortune (and luck) hit Piquet’s Brabham when a fuel line burst and the pump filled the engine compartment with neat petrol which ignited in a merry blaze. Piquet did a crash stop and nipped out hurriedly as fire marshals moved in and doused the flames, but his race was run. A delighted de Cesaris found himself in second place with the demise of the Renault and the Brabham and it was joy day for Italy as Ferrari finished first and Alfa Romeo second. There was some small consolation for the German crowd with BMW M-Power bringing Patrese’s Brabham home into third place. All the hot-shoe Cosworth-powered runners with unblown 3-litre engines were a lap behind. If you haven’t got 600 or more bhp these days you are not in the picture. Engines are indeed the heart of the Grand Prix car, whether they be 120-degree V8, 90-degree V6 or V8, 80-degree V6 or simply 4-cylinder in-line power units. — Denis Jenkinson